The Voicing Technique That All Professional Arrangers Use

The year was 2013, I was a year out of high school and had recently dropped out of a local mechanical engineering degree to pursue my dream of becoming a jazz musician overseas. For some reason, at that time I thought it was a good idea to put together a sextet and record a couple tracks because why not? I mean even today the thought of writing some music and recording still excites me. The only difference was that back then, I had never written a single piece of music, let alone arranged it for an ensemble to play. Maybe I was stupid, or perhaps I had a bit too much self confidence, either way that was the moment I began my arranging journey.

At the time I was going through a rite of passage that every young aspiring jazz bassist goes through and was obsessed with the legendary Jaco Pastorius. As a result, for the recording session I decided that playing one of his tunes would be a good idea. Of course being the jazz nerd I am, it couldn’t be one of the well-known tracks, it had to be some obscure composition that no one had heard of called Domingo. The only problem was there was no sheet music for the instrumentation I had and if I wanted to record a version of it I either had to transcribe it or find another option.

These days I’d consider my ears to be pretty basic compared to many of my musician peers, so you can imagine that back then they must’ve been even worse. That meant transcription was off the table. Instead, I found some random big band score of the tune and decided to try and reduce it. Even though we only had a couple of horns in the group, every time I would harmonize them it was like throwing a dart blindfolded. I had no clue what was right or wrong and just let my ears guide me. And in case you think I’m being modest, this is a period of time where I had zero music theory knowledge, let alone any jazz harmony knowledge.

The recording came and went and in a few years I found myself in an arranging classroom on the other side of the world. Like many university arranging classes, a lot of the content revolved around voicings. I gobbled it all up, and in the first few weeks I was introduced to a voicing technique which would have saved me a whole lot of time when I was trying to revoice that Jaco tune. It’s quite common but very effective. What I’m talking about is how to use close position voicings.

Now many people would think, hey closed position voicings are a basic technique and are not worth discussing. And for some people that may be the case. But they have come in handy hundreds of times in my life and it’s the sort of technique that is revolutionary if you aren’t aware of it. I know my journey would’ve been a lot faster if I had known about them when I got started.

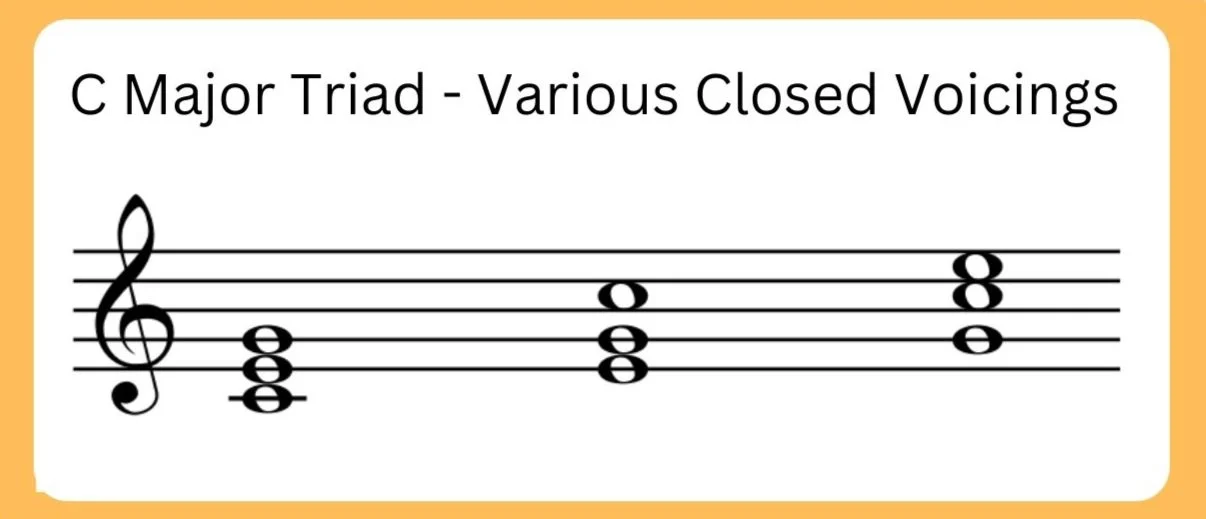

So what is a closed position voicing? Up first let’s look at it from the original classical perspective using a triad. A closed position voicing is simply a triad put together in its most compact form. As a triad is made up of the root, 3rd, and 5th it would be any combination of those three notes within the span of an octave. In the case of a C major triad, it would be all three notes stacked together without any breaks. Eg. C, E, and G, or any of the inversions.

In jazz things get a little bit more complicated as we start to involve extensions and alterations because there are considerably more notes to be fit within an octave. In these cases we generally omit certain notes in favor of others to avoid too many clustered tones. For example, if we had the chord Cma13#11 and wanted to incorporate all of the notes together. It would just sound like one big mesh of sound instead of a cohesive voicing.

Instead, the general rule is to include the fundamental harmony notes (3rd + 7th) as they define the chord quality and then you can fill in the gaps with two other notes from the chord. In this case I’d likely go for at least one of the color tones (9th, #11, or 13th) and see what best fits after that.

One of the best characteristics about closed voicings is that they are highly versatile. Due to encompassing the best parts of a chord, being the fundamental quality and the color, they can be used in an almost endless amount of places. Perhaps you want to voice something out for strings, or other certain instrumental sections like the trumpets, saxes, or trombones. Well closed position voicings are going to be able to get the job done. The only warning I’d give is to watch out for where the voicings land in the register of the instruments you are righting for. This is especially true when voicing for a mixture of different instruments such as a pop horn section.

Just to drive the point home how impactful closed voicings are. If you were to look at any sort of classic big band arrangement, it’s almost impossible to find a score which doesn’t make use of the technique. Whether it's Quincy Jones, Nelson Riddle, or Sammy Nestico, you’re going to find them using closed voicings at some point in time.

Well just like that another week has come and gone. Like I mentioned in the last newsletter entry, the month of January is voicing themed, so next week I’ll be looking at another related topic. One that actually came up in a recent discussion with the participants of my Arranging 101 course this week. When to use voicings, and when not to. Until then, thanks for taking the time to read my newsletter and if you have any questions feel free to reply to this email.

Thanks,

Toshi