What To Do When You Get Bored Of Writing Tonal Music

Well it’s been a moment but I’m back on the newsletter grindstone. The short story behind my absence is that the last few weeks have been a mix of illness, time off, and some bad luck with a broken tooth and a few visits to the doctor. However, I’m back now and hopefully can get back into the swing of things with weekly newsletters once again. I definitely don’t have a shortage of arranging techniques to talk about, and probably even more silly music stories than anyone actually wants to read.

I left off the last entry talking about reharmonization and I want to continue with that theme today but instead of committing to a month on a single topic, from here on out I’m going to see what feels best for the week. That might mean a string of similar topics or a number of unrelated methods depending on what feels right. Of course if there’s anything you want to hear about in particular, just let me know and I’ll try my best to work it in somewhere. Without wasting your time further let’s get into the juicy stuff for this newsletter.

When I was studying arranging at university, I was exposed to so many different techniques. Some I loved, whereas others didn’t really appeal to me (at least at that time). One such technique was abstract harmony, or maybe better known as slash chords or using unrelated bass notes. Having grown up primarily listening to pretty tame jazz from a harmonic perspective, university hit me with a lot of dissonance that I couldn’t really handle or process at the time. I had barely worked out how to hear and understand a secondary dominant when I was pushed into the vast ocean of 12 tone music and advanced jazz harmony.

With a limited understanding and underdeveloped ears, abstract harmony felt excessively dissonant and I really couldn’t see a future where I would actually use it in my writing. Although I can now see applications for it, at the time I would just do the work and complain all the time. After a number of weeks or maybe months churning through writing tasks applying the technique I was relieved to move onto a new topic. The funny thing was, a few months later when I sat down to write my first original big band composition titled Vesuvius, what technique do you think opened the piece?

Somehow in that short period of time I had realized there was a use for abstract harmony. On top of the benefits that Rich DeRosa had demonstrated over various classes, specifically that it allowed for a very specific type of concentrated dissonance, I began to see that it could be used to create a substantial amount of tension unobtainable by functional harmony. With the inspiration to write a piece that mimicked the intensity of an active volcano, it became the perfect option.

As you can see, abstract harmony is definitely not everyone’s cup of tea and even to this day I don’t really use it all that much. Similar to a very spicy pepper, I only cook with it on rare occasions. However, it is a great technique to have in your arsenal of tricks and worthy to be aware of. Especially as it falls outside of conventional harmony options and can help you create unique sounds that are inaccessible any other way.

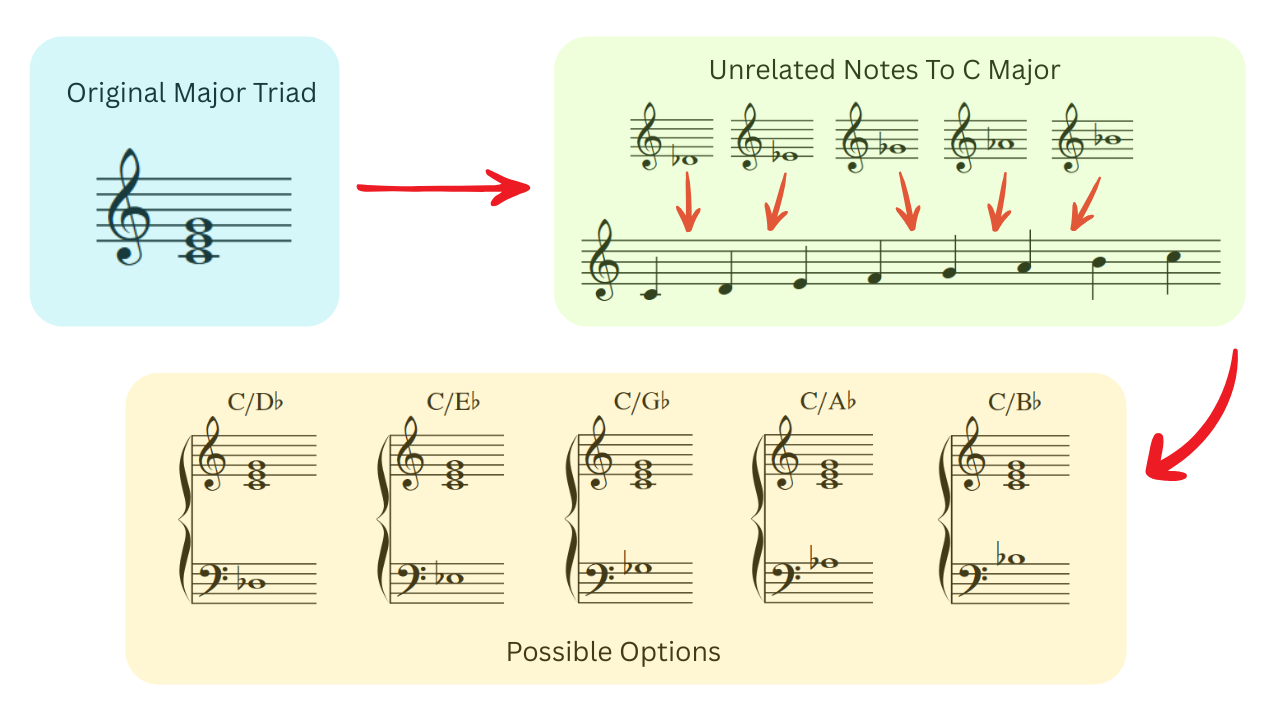

The basic explanation of the method is to use major triads with an unrelated bass note underneath. For example, you could have a C major triad and then put any note outside of C major underneath, such as C/Db or C/Eb. An easy way of thinking about this in C major is to look at the black keys on a piano. Each has varying levels of dissonance with some like C/Bb feeling quite tame as it gives the sound of C7.

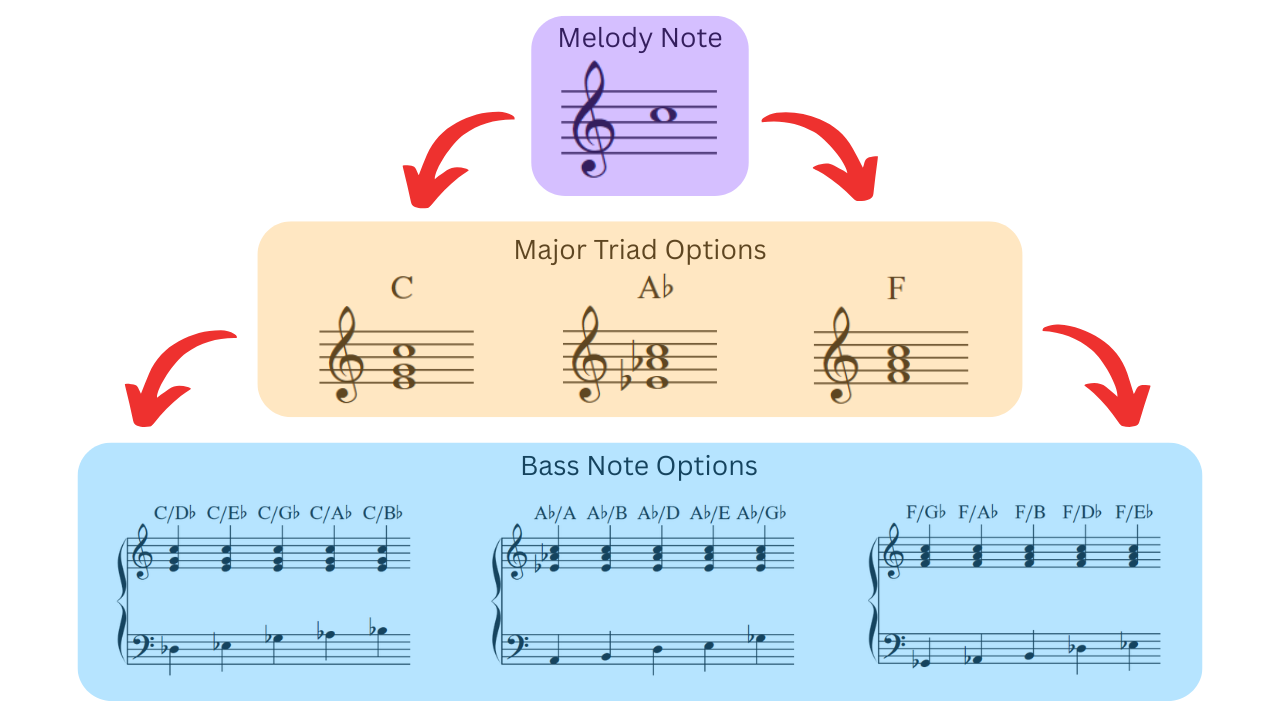

When looking at it from a harmonizing point of view, all you have to do is take your melody note and locate it within a major triad. For example, if you have a C in the melody it could be harmonized with C major, Ab major, or F major. From there you can then look at any of the unrelated notes and test out which one you like the most as a bass note. If you want to think about it from a numbers perspective, any one melody note has 15 different options (3 possible major triads multiplied by 5 unrelated notes per major key).

In reality, often you might not want to assign a unique chord to every single melody note and even if you do, from my own experiments I can assure you that using too much abstract harmony leads to a dissonant mess. Instead how I go about dealing with multiple melody notes is to think about whether they exist within the related major key. For example, if you have a melody which goes E F G, all three notes are within C major and two of them make up C major triad which makes that a perfect candidate for abstract harmony. There’s no fixed rule with when you should change chords but generally if too many of the melody notes start moving outside of the related key it will lead to additional dissonance.

Instead of approaching abstract harmony from the melody, you can also pull the notes from existing chords. This is quite effective to create concentrated dissonance in a functional progression while still providing some kind of harmonic skeleton which follows the original path of resolution. That last sentence is quite the mouthful, so before I become too much of an academic thanks to my wife’s influence (she’s finishing up a thesis currently), let’s unpack what that means practically.

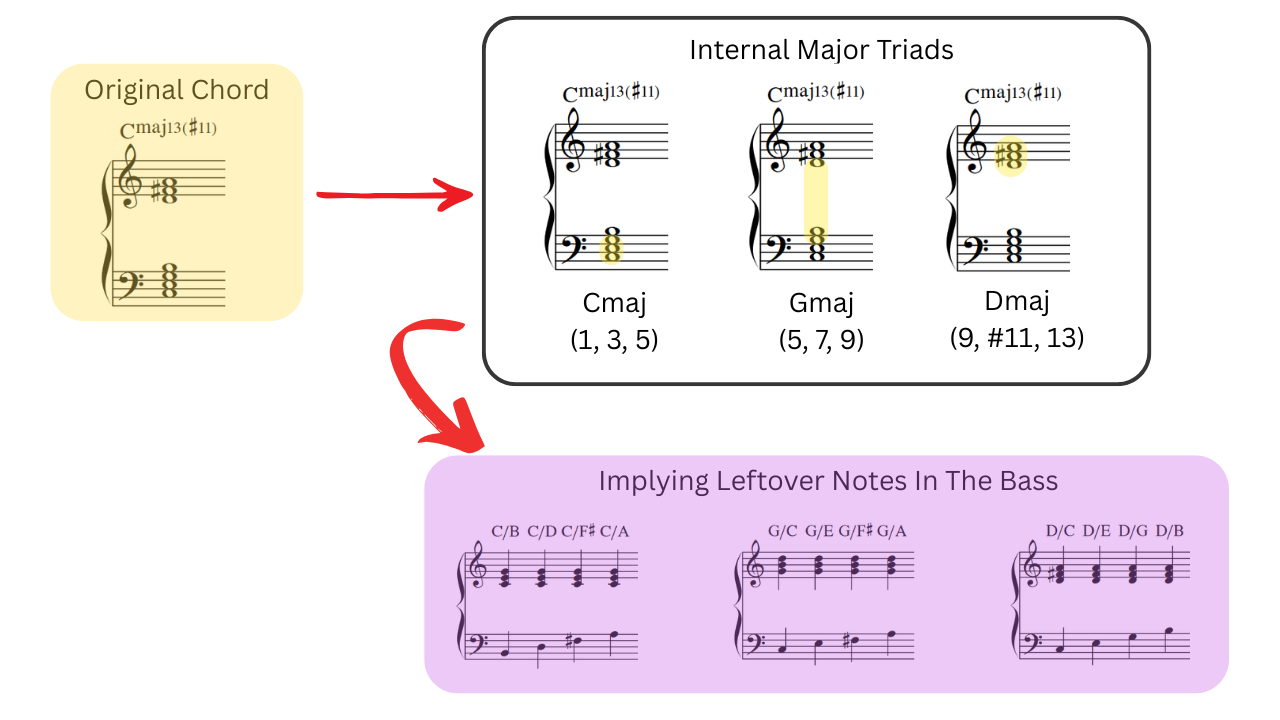

When you have a certain chord such as Cmaj13#11, we can dissect the notes of the chord to create abstract harmony. First we look for a major triad, in this case that could be C major (1, 3, 5), G major (5, 7, 9), or D Major (9, #11, 13). From there we pick one of the remaining chord tones and place it as a bass note. Depending on which bass note you pick, you can retain some level of the original chord’s feeling or move quite far away. For example, if you took the D major triad, your options would be D/C, D/E, D/G, or D/B. In general, you will have more options if the original chord is loaded with extensions and alterations.

The more fundamental notes you keep within the newly created chord (specifically the 3rd and 7th), the more it will retain the same type of resolution as the original progression. This is a great way of reharmonizing a progression without losing the core resolutions, it leaves you with a concentrated version of the original chord where you have specifically brought out only the necessary notes needed for your purposes.

Now you might be wondering whether you can apply this technique to other chord qualities. When I was introduced to abstract harmony it was purely taught with major triads but I’ve since seen at least one example of minor triads with unrelated bass notes (thanks Quincy Jones). I don’t see a specific reason why you wouldn’t be able to as long as you understand that the results will differ considerably from the major triad options discussed. At the end of the day we are just lumping similar sounds together and trying to explain them through theory but what matters the most is that you can find a sound which you like, regardless of whether you can explain it or not. Music shouldn’t be created purely to satisfy theory and these sorts of explanations were only created as a way to understand and replicate music more easily. Or perhaps as sources of inspiration to help you get closer to the sounds you have in your head.

Well I wasn’t expecting this newsletter to be this big but what can I say, I’m an arranging nerd and I like talking about cool harmony concepts. If you’ve stuck around this long, thanks for taking the time to read it all and I really appreciate it. I’m not too sure what I’ll be looking at next week but it’s likely something in the realm of Bill Evans modal harmony or maybe something to do with making music within the restraints of a certain style. We’ll just have to wait and see what feels right.

Until next time,

Toshi