How To Start An Arrangement &

Deal With Writer’s Block

Writing music can be one of the most challenging tasks when you begin, primarily because it relies heavily on creativity. Sometimes the creative juices flow, but a lot of times they don’t. This inconsistency can halt the writing process, especially when you sit down with a piece of score paper and feel uninspired or unsure of where to start. I find it even worse when I’ve already made some progress but then I get to the end of a section and have no clue where to take an arrangement. So how can we get over this hurdle when it inevitably shows up?

The best place to start is with something called an event list. I was introduced to the concept by my former arranging professor, Rich DeRosa, who described it as essentially a plan that organizes all of your ideas into a concise list. This allows you to begin the creative process before writing a single note and process difficult situations ahead of time. As a result, when you inevitably run into writer's block, you can look at the event list for inspiration and avoid breaking your momentum. The best part is that the plan doesn’t have to be fixed; you can always modify it as you go. If you feel the urge to break from it and embrace spontaneity, there is no reason to stick rigidly to your plan. It serves merely as a jumping-off point. An additional benefit of this approach is that it encourages us to learn from other arrangers and their techniques, providing a comparison point or insight into what our favorite composers do from a mechanical perspective without focusing solely on the music itself.

So, what does an event list look like? If you are like me and had to create plans for your essays in high school, you would outline how many paragraphs to include, the topics, points, and examples. You would write these out on a piece of paper. An event list is similar, but it is tailored for your arrangement.

To begin, you might state the style, tempo, and key of your piece, writing down the big ideas, such as whether it features a trumpet or is for a big band etc. Then, you look at the form and break the piece into sections, defining the length of each one. These could include an intro, outro, melody, improvised solo, shout, or soli. There’s no right or wrong option, nor does a section have to be neatly defined.

A great place to begin with is a head arrangement, which includes the head, some solos, a shout section, and then the head again. This format was common in the old testament Basie days, particularly in the Kansas City style, where the band would play riffs. It is a great way to start learning how to write charts as it sounds fantastic and requires not that much effort. Here’s an example of what a basic head arrangement event list looks like.

Head Arrangement Event List

Title: An Exciting New Chart

Style: Swing

Tempo: 120 BPM

Key: C Major

Form: Blues

Section 1 - Intro

Section 2 - Melody

Section 3 - Solo

Section 4 - Shout

Section 5 - Melody

Section 6 - Outro

With that form sketched out, we can start to examine the inner workings of each section. What will happen over the melody? Who is playing the melody? Is it harmonized in unison? Who is playing a counter melody, and what type of counter melody is it? As we explore these aspects, we begin to fill out the entire arrangement. You can be as detailed as you wish. For instance, you might specify that a section should feel a certain way, like Thad Jones, using a particular type of harmony specifically for the saxophones. You could also indicate that a counter melody will utilize certain techniques and that after five bars, it will transition into a different section. You can map out everything in as much detail as you desire.

With all this in mind, this is what a completed event list looks like. Here is an event list for the great Sammy Nestico's tune, "Hay Burner." I aimed to be sufficiently detailed in my approach, not filling in everything I hear but just enough so that I know what is going on. For your own event lists you can adjust the level of detail based on your preferences.

Hay Burner Event List

Reference Recording - https://youtu.be/_Jl9IOqZb7U?si=6CWtz3NbuOESBlaw

Title: Hay Burner

Composer: Sammy Nestico

Style: Med Swing

Tempo: ~120 BPM

Key: F Major

Form: Quasi AABA

Section 1 - Intro

Length: 8 bars

Harmony: Same as A section, loose I/iii vi ii V resolutions with typical dominant subs and some bluesy IV and dim bV options in the mix

Details:

Horns Tacet

Piano Solo sparse ala Basie

Guitar ala Freddie Green

Drums plays consistent swing quavers/8ths on ride, hats on 2+4, bass drum on 1+3

Bass loose two feel

Section 2 - Melody A1

Length: 8 bars

Harmony: Similar to before but with a few added chords

Details:

Melody played by flute and harmon mute trumpet

Rhythm section similar to before but piano does light comping

Section 3 - Melody A2

Length: 8 bars

Harmony: Same as before

Details:

Melody played by Altos and Trumpets (open)

Countermelody hits by trombones, tenors and bari in harmony

Rhythm same as before, slight build at the end of the section into a four feel

Section 4 - Melody B

Length: 8 bars

Harmony: Shifts to the IV chord primarily with the last two bars being a turnaround back to the I

Details:

Melody played by saxes in tritones and octaves

Trumpets play harmonized hits

Trombones + bari play harmonized hits in response to trumpets

Rhythm plays strong 4 feel

Section 5 - Melody A3

Length: 10 bars (felt as 8 with a tag)

Harmony: Same as the other As but with the last two bars being repeated

Details:

Melody played by flute and harmon mute trumpet

All horns play harmonized, decrescendo pads for first two bars out of B

Bars 4+5 full band harmonized hits around melody

Bars 6-8 trombone + bari hits

Bar 10 full band unison/octave melody

Rhythm goes back to a loose 2 feel, piano more prominent on upper register pads

Section 6 - Shout A1

Length: 8 bars

Harmony: Same as the other As with a few more colorful extensions and substitutions

Details:

Tutti horns on harmonized melody

Rhythm plays 4 feel, drums ala shout section reacts to horn parts

Section 7 - Melody/Piano Solo A2

Length: 8 bars

Harmony: Same as the other As with a few more inversions

Details:

First 4 bars sax melody in true unison

Bars 3+4 trumpets harmonized counterline, wahs in plunger

Bars 5-8 piano solo ala Basie

Rhythm light 4 feel

Section 8 - Sax Soli Bx2

Length: 16 bars

Harmony: Same as the other B but twice as long

Details:

Sax melody in five part harmony

Bars 3+4 trombone hits

Rhythm light 4 feel

Section 9 - Pedal

Length: 9 bars

Harmony: V pedal with moving color tones (Gm7/C, Abdim/C)

Details:

Bars 1+2 trombones harmonized melody with sax unison/octave pads

Bars 3+4 sax harmonized melody with trombone unison/octave pads

Bars 5+6 brass harmonized melody with sax unison/octave pads and hits

Bars 7 + 9 full band harmonized melody

Rhythm stays similar with bass emphasizing 2+4 on the pedal and building, drums fill in bar 8 to setup horns

Section 10 - Shout A1

Length: 8 bars

Harmony: Same as other As

Details:

Tutti harmonized horns

Rhythm on swinging 4 feel with drums filling ala shout section

Section 11 - Piano Solo A2

Length: 8 bars

Harmony: Same as other As

Details:

Bar 1+2 unison/octave melody in saxes and trombones (echoes last statement in the shout)

Bars 3 onwards piano solo ala Basie

Rhythm light 4 feel

Section 12 - Shout/Riff B

Length: 8 bars

Harmony: Same as other Bs

Details:

Saxes play repeated melody riff in octaves

Trumpets and trombones play harmonized call and response type lines, eventually come together in the last two bars

Rhythm play swinging 4 feel, drums sometimes acting like a shout section (specifically the end)

Section 13 - Melody A3

Same as section 5 with different tutti line in final bar

Section 14 - Outro

Length: 8 bars

Harmony: new progression, hasn’t been used elsewhere in the chart

Details:

Bars 1-4 tutti harmonized horns ala shout section

Bars 5-6 melody restatement by unison saxes with harmonized pad in brass underneath

Bars 7-8 tutti harmonized horns

Rhythm mixture of 4 feel and doubling rhythms in horns

Stealing Isn’t Always Bad

Back in 2015, I was tasked to write my very first big band arrangement for a class I was taking. I knew all of the techniques, how to voice certain sections, and generally had the mechanics down but I had never written a big band chart before. At this point in my journey I knew what an event list was and had even used them in combo arrangements. However, I found the idea of tackling my first big band chart extremely daunting and wasn’t confident that an event list would work.

Fortunately one of my mentors at the time, Drew Zaremba, provided a genius suggestion and one which I still use to this day. He said that I should simply copy the event list of my favorite big band arrangement. At first I challenged the idea, thinking that my chart would come out as a carbon copy of what I was listening to. Drew pointed me to one of his recent arrangements at the time and asked if I could tell whether he had copied the event list. Of course it was impossible to tell and when I admitted that I had no clue he revealed the original chart he had stolen from. To my surprise it sounded nothing like his arrangement. The only aspect which was comparable was the underlying structure but all of Drew’s lines were unique.

Looking at Drew’s advice from another angle, I realized that it was no different to copying the foundation of a house. Just because many houses are built with similar foundations and feature a certain amount of rooms, doesn’t mean that they look or feel the same. The best thing about using this approach with event lists is that you get to build off tried and true methods from big band arrangements you already like the sound of. Because of this, when you’re just starting out or are unsure how to plan an arrangement, copying another event list sets you up for success right from the get go. And if you have doubts about this method, just have a listen to pop radio and see how many people care that the majority of songs share the same form, chord progression, and even melody these days.

Another benefit of this approach is that it can help you be more creative. After I had completed my first big band arrangement, many of the charts I wrote afterwards used the same event list. You know, if it ain’t broke why change it? Well, over time it created a new problem. A lot of my charts started to feel a bit repetitive and I lost my creative spark when it came to planning out an arrangement.

To get out of the rut I decided to listen to a few contrasting big band recordings and write down the event lists. By doing so, many options for planning an arrangement were revealed, each of which were completely different to how I had been approaching my arrangements. I was still using the same writing techniques, but now the structure of each chart changed and showed me new possibilities of connecting sections together.

With this in mind, I would highly suggest you go out and listen to a variety of big band recordings. Copy down the event lists for the ones you like, and then compare them to one another. As a result you’ll see pathways you may never have thought of before, and once you feel confident enough, you can start mixing different aspects of event lists together to create unique solutions. It will give you a very good idea of how sections work in big band arrangements.

Sections, Sections, Sections

Writing an event list is great and all, but if you don’t know the terms for the techniques and sections used by an arranger it may be hard to get started. There’s nothing wrong with coming up with your own as long as you can explain them to others. However, below you’ll find a list of common terms that arrangers use so that you can communicate more easily. Note that this is not an extensive list and you can add to it.

Section Types

Head/Melody - a section where the main melody is being played

Intro - the start of a song, generally sets up the mood and comes before the first melody section

Outro - the end of a song, generally sounds conclusive

Solo - some type of improvised solo, typically accompanied by the rhythm section

Soli - a written section/phrase that captures the nature of an improvised solo but features more than one instrument, typically a similar group of instruments (eg. sax soli, trombone soli, trumpet soli)

Shout - a simplified melody section with many instruments being in the upper register, generally the horns are tutti

Pedal - specifically refers to the accompany harmony which features a static bass note

Hits - has two definitions: 1. A countermelody technique 2. A section where the full band plays tutti hits

Vamp - a looped section, typically used under a solo or some kind of vocal dialogue

Breakdown - the orchestration is reduced to a small number of instruments, commonly used as drums only with additional rhythm section instruments being added over time

Too Many Cheeseburgers

Inevitably you’ll face a time in your writing journey when you fall in love with certain techniques and overuse them in your writing. It happens to everyone and is not necessarily limited to the planning stage of an arrangement. However, in my journey it did.

You see, I love the sound of shout sections. While in university I had the chance to write a few big band arrangements and for my final recital I got to stand in front of a big band and conduct them through my charts. Other than being incredibly overwhelmed due to lacking any sort of conducting ability, the experience changed my perspective of big band forever. In the last song of the night we played my arrangement of A Night in Tunisia, and for the first time I got to experience the wall of sound that a big band can create when it is firing on all cylinders. I was hooked. I knew I already loved big bands but the feeling of that many horns moving that much air paired with the intensity of a swingin’ rhythm section changed me. For better or worse, every big band chart I wrote from then on focused on shout sections and high intensity moments. Unfortunately, I didn’t know that there was a point where it was too much.

That was until I got to the start of 2020 when I decided to write an original 45 minute suite for a local heavy weight trumpeter. Everything went well at the performance, the band smashed it out of the park, and the soloist exceeded all expectations. I was on cloud nine, well until I decided to ask him how he felt about it. The trumpeter mentioned that the whole suite was a pretty long blow with a majority of it being high energy. There was no room for the composition to breathe, no middle or low intensity sections. Of course his words hit me like a hot knife through butter as I had just spent countless hours writing the suite for him. But at the end of it all I knew he was right.

What had happened was that I had gone well and truly past the appropriate number of shout sections and high energy moments in the suite. The conversation took me back to something Rich DeRosa once told me. He said that everything has a saturation point and once you exceed that point you must change the situation musically. To make his point memorable he compared it to a McDonalds cheeseburger. When you eat a burger it tastes great and it may inspire you to buy another, but if you keep eating more burgers, at some point you can’t fathom the idea of eating another. The key is to know when you hit the saturation point and to then pivot. He used the example of drinking a soda to cleanse the palate, and surprisingly when you do so, a burger doesn’t feel nearly as bad again.

Going back to my situation, I had reached the saturation point of shout sections in the suite. In the words of Rich, I’d eaten too many cheeseburgers. The piece would have been better if I had shifted gears more often and offered more contrast in the sections. This could have been done in many ways but I had stubbornly not done any of them due to my love for hard hitting big band moments.

Bringing this back to planning an arrangement. It is important to look at what types of sections you are using and how often you use them. In a single arrangement you are unlikely to run into the problem of having too many of a single section but as soon as you look at programming a whole show or want to write a longer piece, having too many cheeseburgers is a definite issue. To combat saturation points, once we have our event list we can begin to consider the bigger picture of an arrangement. Looking at the arcs of certain characteristics like dynamics, rhythm, emotion, and what sort of density they use throughout a piece. In some cases you may want the whole piece to be roaring, in which case having consistent shout sections won’t be a problem. The key is that you were aware of that decision before you performed the arrangement.

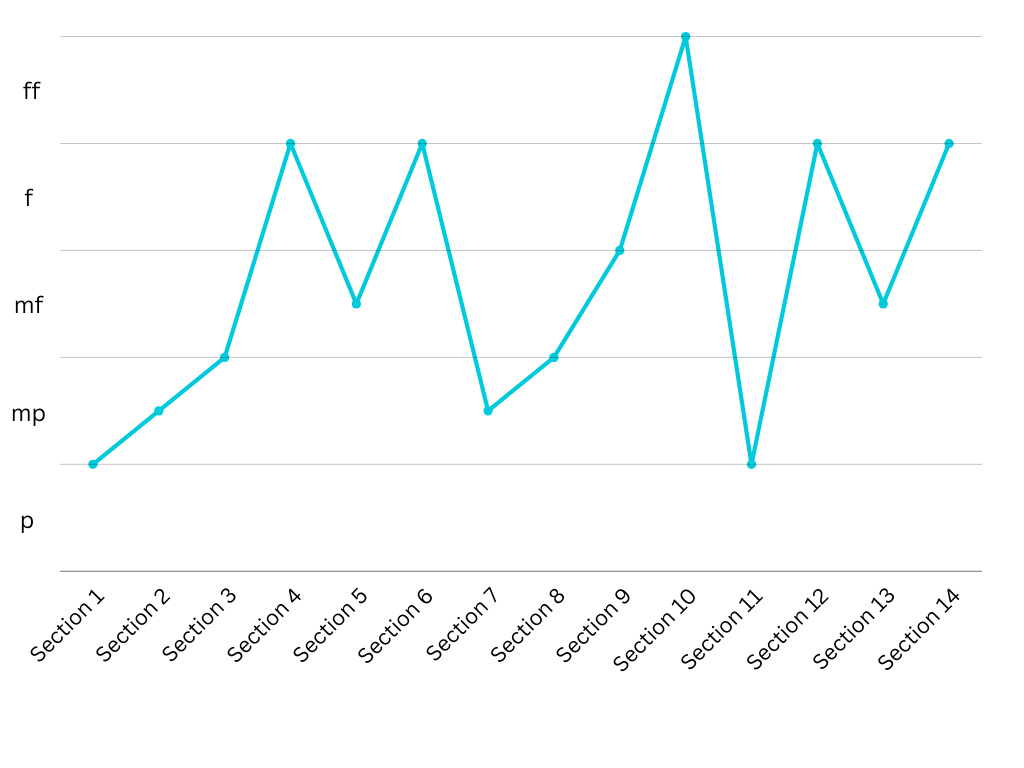

To map these aspects alongside an event list requires a more creative approach. We could go through and simply write softer, louder, or loudest next to the appropriate sections but that doesn’t always give us an accurate portrayal when planning. Instead I opt for graphs as a secondary resource that accompanies an event list. For instance, if we were to graph out the dynamics for Hay Burner per section it would look like this:

There is definitely room for more nuance in the graph but by generalizing each section from the event list, we get a snapshot of how the dynamics move throughout the composition. We can also use this technique to map out many other aspects of the chart, including, but not limited to, rhythm, orchestration, instrument register, harmony, style and improvisation. For example, by focusing on rhythm you could look at how densely packed some sections are compared to others. In Hay Burner the shout section has far more quavers/8th notes compared to the intro, with the melody sections somewhere in between.

The take away from this approach is not necessarily to graph out everything but more to think about the flow of each of these elements while planning. When I plan, often I’ll sketch out a few outlines on a piece of scrap paper just so I have a better understanding of the shape of the whole arrangement. By thinking this way we take ourselves out of the individual phrases and sections, and start to look at the big picture.

Going back to cheeseburgers, by thinking about the arrangement in a variety of ways you can avoid hitting saturation points. You’ll start incorporating more balance across every aspect of your arrangement, and more importantly, you’ll be able to create contrast between each piece you write.

The Takeaway

Trying to force creativity is one of the most frustrating situations to deal with. Unfortunately, when you’re an arranger you’ll inevitably be faced with it at some point. In my experience, constraints help the creative juices flow, and when you pair that with a great plan, almost always it can get you out of a rut. For me, that process takes the form of an event list and it's something I try to incorporate at the start of every arrangement I write.

As you’ve just read, event lists operate as a plan of attack for an arrangement and when you don’t know how to create your own, you can always copy one from your favorite recording. Once you have a few arrangements under your belt, you can then take things a step further and think about the big picture through density graphing and avoid eating too many cheeseburgers. Just remember that these are not fixed approaches and at any time you can break from your plan and embrace your creativity in the moment. They are simply there to help you get started when you sit down to write.

Now that you know how to plan an arrangement it’s time to understand the techniques behind the actual note writing. That means looking at harmony, harmonization, orchestration, substitution, and so much more. Up first we are going to tackle harmony by breaking down tension and resolution.