How Intervals

Create Emotion

When I got my start arranging the last thing I cared about was intervals. I wanted to use the flashy chords with lots of notes and get into the advanced techniques as quickly as possible. I definitely didn’t want to spend any time looking over an introductory level concept.

However, now that I’m older I realize how important intervals are in shaping emotion. Yes they are the building blocks of Western music and are taught with beginner theory, but they are also the foundation for how every note relates to one another. Drawing a similarity to food, they are individual ingredients and collectively they create different tasting experiences. If you look at any arrangement you instantly see how many intervals exist, with one piece featuring tens of thousands if not more.

By mastering the different emotions associated with intervals, an arranger can create listening experiences which reflect whatever feeling they want. Depending on the context, a minor 2nd may feel jarring and create immense pain, or it could sound clunky, or perhaps like a mistake and almost comical. As I get older I now think of the minimal amount I need to write to capture an emotion. Sometimes an eight note chord is warranted but many more times just one certain interval gets the job done.

On this page we will be looking at common emotional associations with intervals, specifically the qualities an interval takes on in a vacuum. From there we will add a layer of context by building a triad from intervals, showing how not all intervals are heard equally when combined together. Understanding these two steps alone have the power to transform how you write and how well emotion is conveyed in your music.

What are Intervals?

Harmony is created by playing at least two notes at the same time with the interval between them offering a spectrum of emotional options to a composer. As emotion is subjective, so too is how we interpret each interval in the Western music system. Context reigns supreme, with setting able to change how one interprets an interval, whether that be the intervals within a standalone chord, between various instrument textures, or within different key centers. So how do we start to understand intervals?

The go-to for Western music theory is to look at intervals in a vacuum, to understand them in the most simple form and to build off of that knowledge by looking at real world examples. Within an octave there are twelve unique intervals, which vary in stability and dissonance. Below you will find how I interpret them, however I would challenge you to come up with your own associations. Please note that I have put all of the intervals in relation to C but they can exist between other notes too.

Unison - Stable, Consonant, Strong

Minor 2nd (m2) - Unstable, Highly Dissonant

Major 2nd (M2) - Low Stability, Consonant, Harmonic Cushion, Bright

Minor 3rd (m3) - Stable, Dissonant, Sad, Bluesy

Major 3rd (M3) - Stable, Consonant, Happy, Bright

Perfect 4th (P4) - Stable, No Sense of Harmony, Dark

Tritone (TT) - Unstable, Highly Dissonant

Perfect 5th (P5) - Stable, No Sense of Harmony, Open, Bright

Minor 6th (m6) - Stable, Dissonant, Dark

Major 6th (M6) - Stable, Consonant, Bright

Minor 7th (m7) - Low Stability, Consonant, Bluesy

Major 7th (M7) - Unstable, Highly Dissonant

These definitions are only meant to be a starting point, so experiment on an instrument or with MIDI and see what emotions you start to associate with each interval. Build your own list to reference when you compose and remember that context can effect how you perceive each interval. For instance, intervals exist between each note in a key which means that in C Major the m3 between E and G may feel completely different to the m3 between A and C. Use your best judgement as to what interval matches your intention.

Understanding how you perceive intervals will come in handy later when you start composing melodies and when you harmonize any given line. Here’s an interval list template so that you can start noting how each interval makes you feel.

Combining Intervals to Create Chords

By combining multiple intervals together you can create chords. In their simplest form, chords are typically made up of three different notes within a key center, however, sometimes they can be more complex and take many different shapes. Regardless of the chord you are using, to understand the overall sonority it is helpful to look at the intervals the chord is made up of, similar to looking at the ingredients used when cooking a meal to understand why it has a certain flavor.

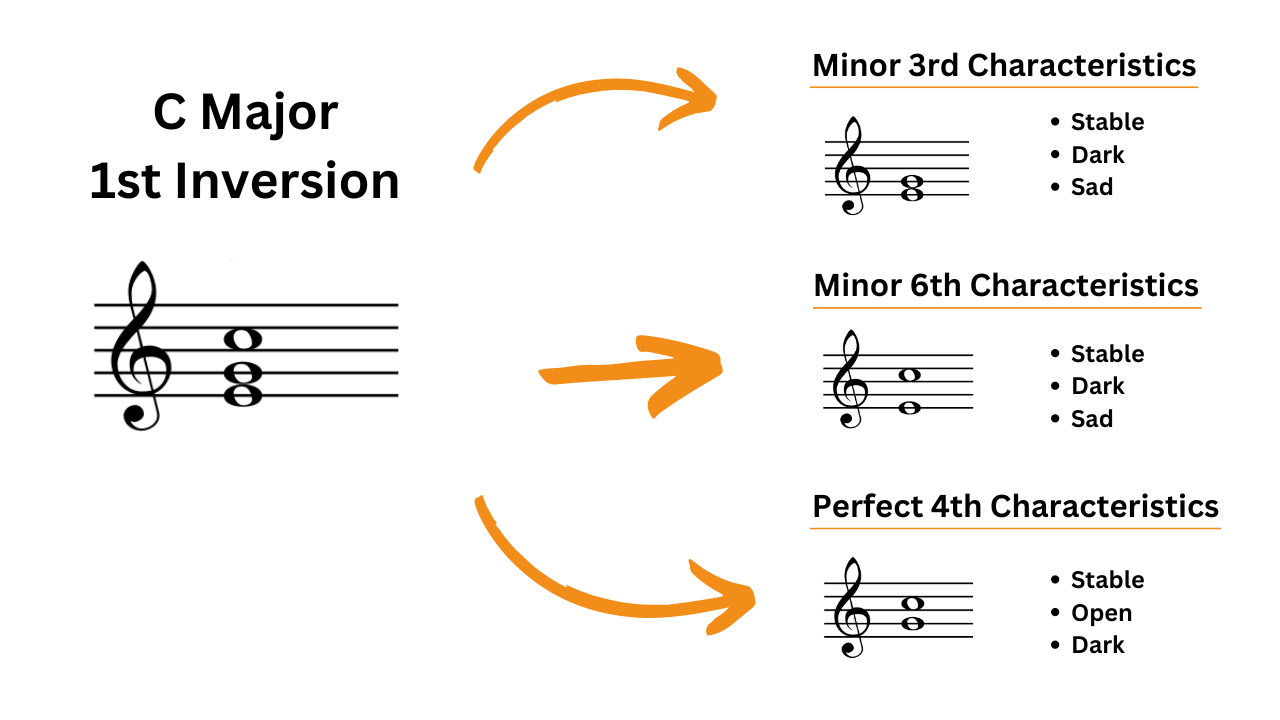

For example, the C major chord is made up of the notes C, E, and G and is generally considered a happy, stable sounding chord. But why is this the case? Well each of the notes have intervals with one another which create the happy sonority. The M3 between the C and E is stable and bright, and the P5 between the C and G give an open sound to the chord, providing the foundation of a stable, happy sound. In a root position voicing where C is placed on the bottom of the chord these two qualities are more prominent compared to any inner intervals such as the m3 between the E and G. That is why even though a major chord has a m3 within its structure, an interval which is typically seen as dark or sad, the overall sonority is happy. However, if you were to reorganize the intervals in a different way such as in an inversion, different emotional qualities would be highlighted and you could bring out the emotions of the inner intervals.

Inversion is a simple technique which can drastically alter the overall sonority of a chord. By replacing the bottom note of a chord voicing with any one of the other notes in the chord, the priority of intervals changes and can cause a bright voicing to become dark or vice versa. Inversions can also impact chord functions within a key center, reducing the overall sense of resolution a diatonic chord may have.

Taking the example of a C major chord used earlier, by putting the E on the bottom instead of the C, the interval strengths are reorganised, making any intervals with the E a higher priority to those with the C. This results in the m3 between the E and G, and the m6 between the E and C creating a darker sonority than the root position voicing discussed above. Even the inner voice interval of a P4 between G and C is considered darker than a P5, contributing slightly to the overall somber sound.

However, it’s likely when you first heard this example that the chord sounded just as bright as the root position triad. That’s because you are hearing the inversion in the context of C major and not in a vacuum. To demonstrate further, here is an example of a chord progression in C major that finishes on a C chord in first inversion.

When it finally resolves to the C/E chord it definitely doesn’t feel dark. What we can take away from this is that the context of the key or progression can bring out other emotions from each interval which may override the individual feelings we hear in a vacuum. Because the notes of the inversion are made up of the chord tones from the C major triad, within the key of C major they will generally take the characteristics of that key (bright/happy). That doesn’t mean the dark feelings aren’t present, they are just muted considerably.

To change that context and see how you might start hearing the darker qualities of the inversion, here’s a famous example from the James Bond theme.

The inversion sounded much darker this time because it highlighted the fundamental notes of the key of E minor with the C being felt as the b6, a much more dissonant tone in this context. As you can imagine, there are many different contexts that you could put a single chord which would impact how you perceive it emotionally. That may feel overwhelming to begin with, so I would suggest understanding one at a time and experimenting with more options once you feel comfortable.

The Takeaway

Intervals are at the core of Western music and contribute significantly to the emotions we feel when listening to music. To understand how they do this we should look at them in a vacuum and list how they make us feel. From there we look at grouping them together (with triads being a great first option) and understand how the effects of each interval come together to create the sonority of a chord. Unfortunately, music doesn’t normally exist in a vacuum so the final step is to start to understand how each chord or interval operates in a given context. I would suggest starting with certain keys that you are familiar with and noting how each chord feels within that context. You’re in luck because there’s a system which has been created to help us quickly understand how diatonic chords feel within various key centers. In the next section we will explore the system and unpack where tension and resolution naturally occur in a major key.