How To Make Any Chord

Progression Sound “Jazzy”

Like many of my peers, I was introduced to the concepts of harmony through various high school music classes. I learnt the basics about chord shapes and how to identify them by ear but not too much more than that. When I began more advanced theory classes at university I was blown away by everything, there was so much about music I didn’t know. Every semester introduced new concepts that changed my perspective on the music I loved. Sometime in my first year I tried writing music with the techniques I was learning. Unfortunately, even though I had learnt a lot, I wasn’t happy with the chord progressions I created.

You see, I was enrolled in a jazz studies program but in the first year I primarily took classical theory classes like all of the other freshmen. I was learning amazing techniques that worked in the classical world but for some reason when I brought in compositions built around those techniques to my jazz ensemble rehearsals, they never felt quite right. Not really fitting into the sound of the charts I was inspired by, such as compositions by Herbie Hancock or Miles Davis. I kept experimenting but couldn’t quite find the solution. Fortunately, in my second year the arranging professor Rich DeRosa solved my problem.

When I started learning arranging, Rich told me that the key to making something sound “jazzy” was by including color tones. More specifically, extensions and alterations. Jazz itself shares a lot of similarities with the classical world, especially when it comes to functional harmony. They both share the same type of resolutions, and for the most part jazz is built on exactly the same sort of diatonic triads and 7ths that classical music uses. However the main harmonic difference is that chords generally have more notes in jazz. This is achieved by stacking additional tones above the set chords, extending the harmony into a second octave. Another option is by altering certain chord tones by a semitone/half-step up or down. Up until that point I had not been including any of these extensions or alterations into my compositions, resulting in a more “classical” sound. Once I had received the advice from Rich, I immediately started loading up all of my chords with as many extensions and/or alterations as possible. And you know what, I my music started to feel like it belonged in a jazz setting.

Ironically, I didn’t really know what I was doing other than sticking 13ths, or #11s on various chords. Looking back on those earlier charts, there are definitely some chord symbols that don’t really make any sense, but hey, at least they were one step closer to the solution. After a few months of experimenting with chords I started to find certain sounds I liked. Namely, Dom7#5#9 and Dom13#11. I know I'm not alone in liking those chords because a lot of my peers used them just as much as me, and even ten years later I still use them a lot. My new problem was that I was recklessly trying to make my charts sound “jazzy” but not really understanding the nuance behind using extensions.

A good way of thinking about extensions and alterations is to think of them through the lens of painting color. The fundamental harmony of a chord (root, 3rd, 5th, 7th) represent the primary colors, whereas extensions and alterations offer different shades. For example, let’s say a minor chord is the color blue, well when you add a major 7th and then a 9th and 11th, it becomes considerably darker and depressing. Compared to a minor 7th and a 13th where the chord would be a brighter blue and feel slightly happier. Another comparison could be to food, with extensions and alterations being various spices. Some alterations like the b9 add more dissonance to a chord and could be represented by something like cayenne powder, something that adds a lot of spiciness to a dish. Whereas a normal 9th may be something more neutral like garlic powder, something which adds complexity but doesn’t necessarily alter the overall flavor quite as much. Whichever way you look at it, extensions and alterations create a new playing field for harmony and when I first was experimenting with them I had no clue what complimented each other and what didn’t.

The great thing was that over time I started to work out which sounds I liked and began to associate certain extensions with emotions. My writing improved and the choices I made were far more coherent with one another. However, it is hard to teach perception as everyone associates differently with chord shapes. As a result, I created a system of teaching extensions which limits your options and builds off of classical theory. Allowing a much easier entry point to the topic compared to the process I went through, and one which gets you to the end result more efficiently. Before diving into the method, It is important that you understand functional harmony, specifically the chords of the major and minor scale and how they want to resolve. If you don’t, I’d suggest reading through this resource first as that topic is the foundation for understanding jazz harmony.

Expanding The Diatonic Chords

One of the most asked questions I get when I teach arranging is what extension to use and where to start. As you just saw, my introduction to these color tones was somewhat chaotic but yours doesn’t have to be. For those unsure exactly what an extension or alteration is, an extension is simply any chord tone that is not one of the fundamental four notes of a chord (root, 3rd, 5th, 7th) and is typically place above an octave from the root note. An alteration is the name we give any note which is modified by a semitone/half-step, for example if you shift a 5th down a semitone it would be called a b5th and thus be an altered tone. They are easy to identify as they will have some kind of b or # symbol infront of the scale degree.

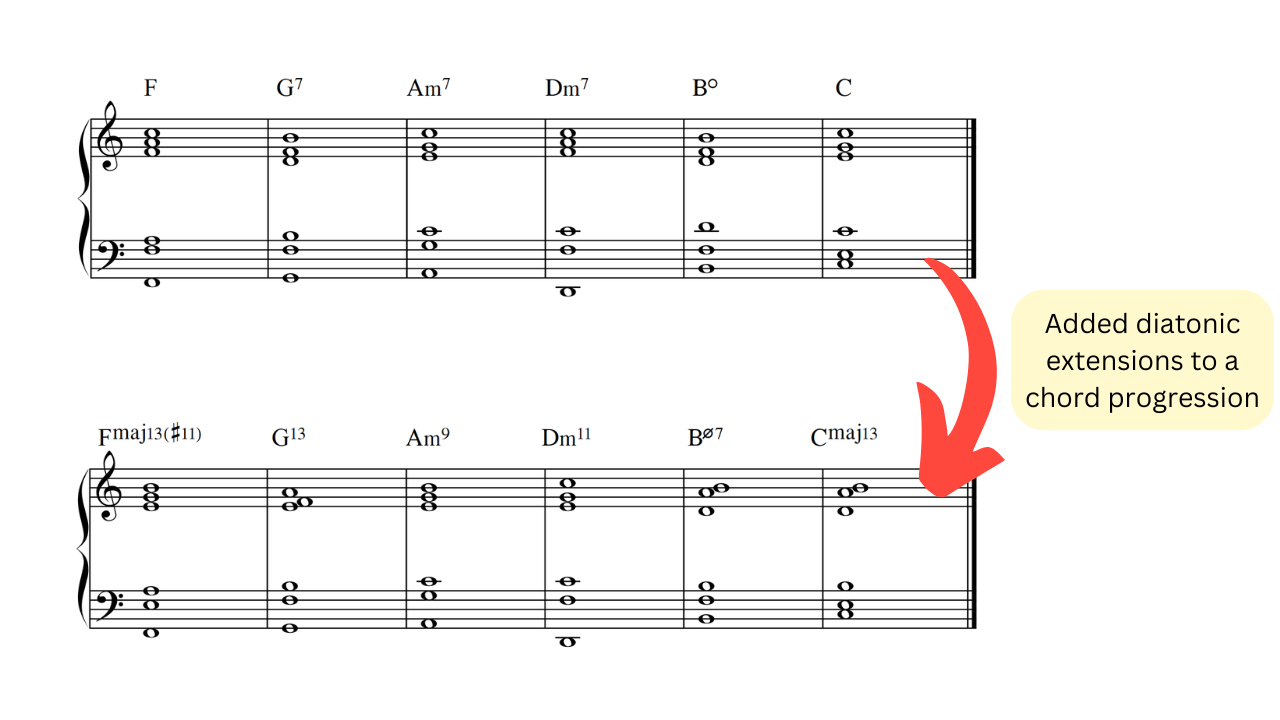

In a similar fashion to unpacking the diatonic chords of any particular major or minor scale, each chord has a number of extensions and alterations which naturally occur due to the notes in the scale. Instead of just having three or four notes stacked on top of each other to create a triad or 7th chord, you can keep stacking the diatonic notes until you eventually get back to the root note again. For example, an F major chord in the key of C major would be stacked F, A, C, E, G, B, D before it reaches F again. That would leave us with an Fmaj13(#11) chord instead of the traditional Fmaj.

Just like that you now have naturally occurring extensions and alterations with the chords you are already familiar with using. You can pick and choose which color tones you like over each chord and slowly build up your own association with them. Of course, you can do what I originally did and put everything and the kitchen sink on every chord and call it a day, but the main thing to realize is there is no bad way to go about beginning to use extensions.

However, there is a certain interval that is typically avoided when using extensions/alterations which may cause a few to be omitted. It is the minor 9th and is considered the most dissonant interval of them all (even more than a tritone). Going back to the food analogy, the minor 9th would be comparable to a ghost pepper or something even spicier and should be handled with care due to how it can impact the music. Of course you can use chords which include the interval but just be mindful of how it can impact an arrangement.

When you use extensions, you are introducing notes with an extra octave above the original which means you need to be aware of where a minor 9th might exist within the inner intervals of a chord. There is nothing inherently wrong with using the minor 9th, but you should at least be aware of its presence and use it when you want to and hopefully not by accident.

When examining the diatonic chords of a major scale with extensions, identifying where the minor 9th exists can be challenging at first. Fortunately there is a trick to finding it quickly by identifying where the semitones exist within a major scale (between the 3rd and 4th, and 7th and 8th degree). This works because a minor 9th is simply a minor 2nd but with an added octave. Therefore, any diatonic chord which uses the 4th or 8th degree as an extension above the 3rd or 7th respectively will include a minor 9th interval.

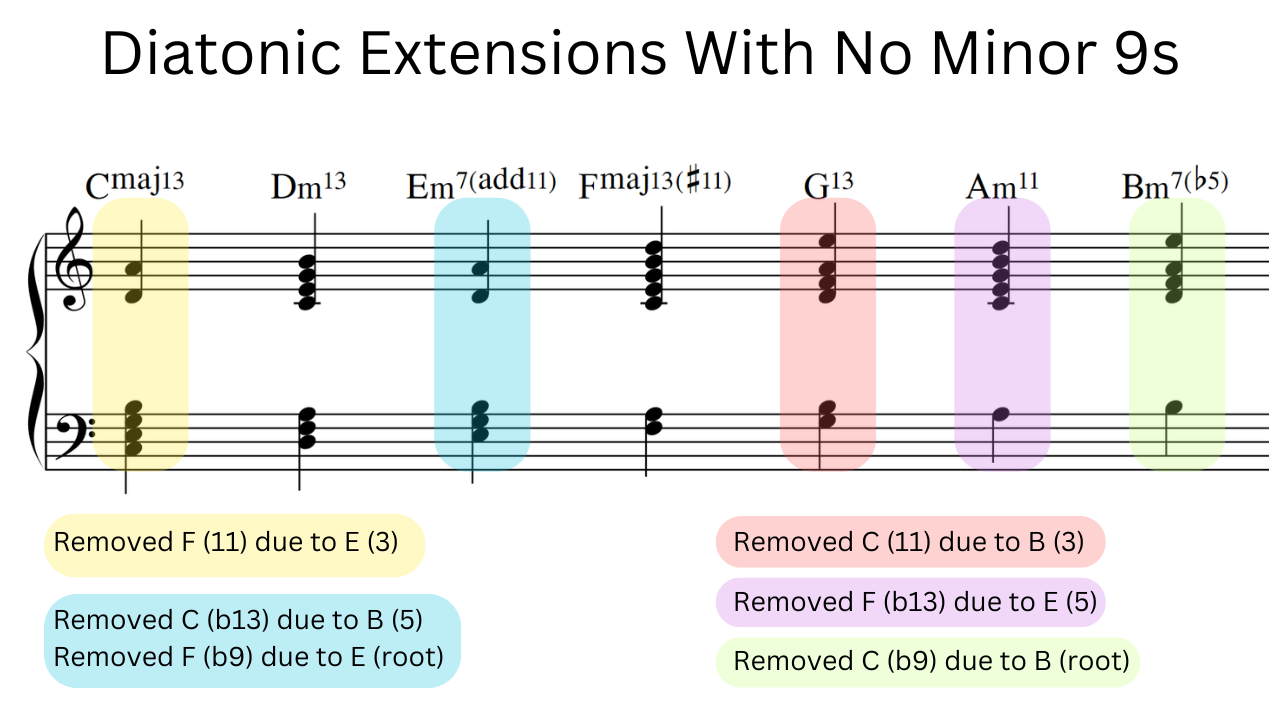

For example, if we take the first chord, C major, with the added 9th, 11th, and 13th, we can see that it uses both the E and F, which are the 3rd and 4th degrees of this key. In this context, the F acts as a minor 9th above the E, creating dissonance. Looking at the other diatonic chords there are a few other common places that we find these minor 9ths. For example, in the E minor chord, the interval exists between the E (root) and the F (9th), as well as between the B (5th) and the C (b13th). You can also find it in the G7 chord between the B (3rd) and C (11th), in A minor, between the E (5th) and F (b13th), and in the B diminished chord between the B (root) and C (b9).

Now that we know these chords include some form of the minor 9th interval, what should we do? Well, you can keep them as they are if you like that sound; there is nothing wrong with that. However, if it creates an unwanted dissonance, the simplest solution is to omit the minor 9th. For instance, in the C major example, we can remove the F (11th). This is a straightforward yet effective solution that allows you to add color through the other extensions while eliminating unwanted dissonance. Here’s what the diatonic chords of C major look like when you remove the minor 9th intervals.

Another option is to revoice the chord. Instead of maintaining the minor 9th format, you can invert the notes to create a major 7th. For example, using the C major chord again, instead of having the F as the 11th, you can think of it as a 4th and voice the E above it. This way, the E can be perceived more as a 10th rather than a 3rd. This approach gives a more suspended sound as the foundation, which is interesting but may not align with what you are aiming for when starting with the C major triad.

None of these options are inherently bad; you can use any of them, but it is essential to be aware of the choices available to you.

Which Extension or Alteration to Choose?

So how do we effectively use color tones? With all these options at our disposal, how do we determine which ones to choose? If you are like me, you might want to experiment with all of them initially, as there is nothing wrong with incorporating as many extensions as possible. However, from a color perspective, this can add complexity that may be difficult to grasp from the outset.

Instead, it is beneficial to familiarize yourself with one extension at a time. If I were to start over, I would advise myself to do this, as it allows for a deeper understanding of each extension and helps form an association with the feelings they evoke. As I continue to write, I find myself focusing on one or two extensions or alterations rather than using all of them. This approach enables me to highlight the specific feeling or emotion of a single extension.

For example, a #11 has a remarkable sound when it stands alone alongside the fundamental harmony, allowing you to truly appreciate the emotion it brings. However, if it is surrounded by the 9th and 13th, its impact can be diluted. While it remains present, the abundance of other colors can make it harder to discern. Similarly, consider painting: if you place something bright orange on a canvas, it stands out. However, if you surround it with more delicate shades its distinctiveness may diminish.

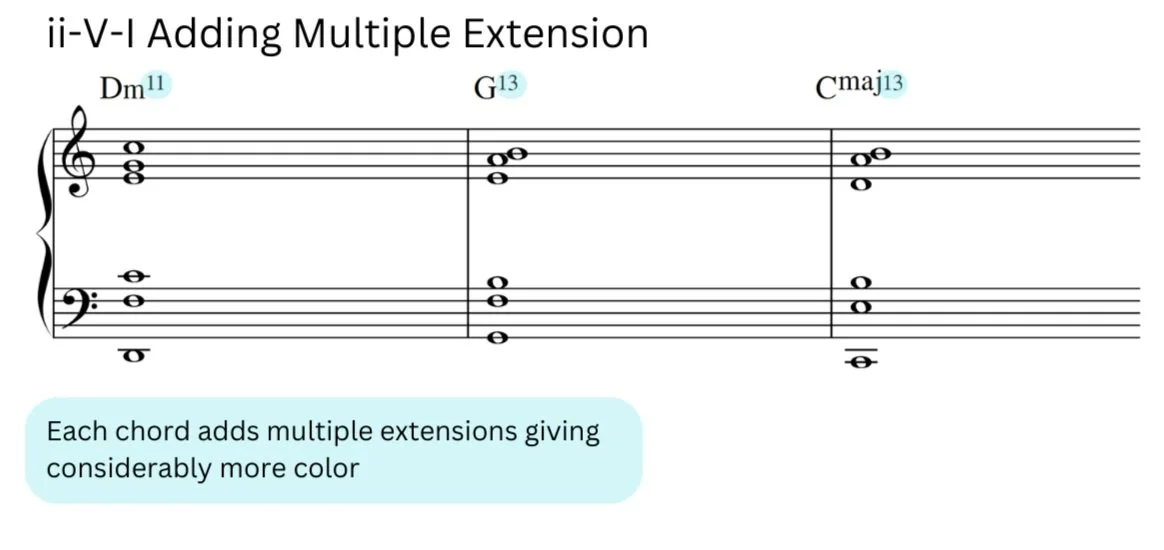

Let’s have a look at doing this in practice. Take a straight forward ii-V-I progression and add different extensions individually, noting what sort of feeling you associate with it. Once you feel comfortable with each individually, start experimenting with combinations like the 9th and 11th together. Eventually you will get to a place where you may even add three different color tones at once. It is important to note that like intervals, our perception of extensions/alterations will change depending on the context. However the underlying feelings you perceive while listening to them in a vacuum will still be present, they just may be to a smaller or larger degree depending on the key signature and what has happened prior in the chord progression.

Linking Scales to Harmony

Now that we understand the foundation for where extensions and alterations exist diatonically, we can look at other places for inspiration. A key method that can help is a concept called chord scale theory. If you're an improviser or attended jazz classes at a university level, it's probably something you've been introduced to at some point when you've taken a jazz improvisation or theory class. The main concept is that every scale has an associated chord that it implies, or conversely, that every chord has an associated scale that can be used against it. When we write, this can be really helpful because if you have a certain sound you like from a chord, it means you can generate a scale and ideally a melody. Or if you have a great melody, you will be able to find an accompanying chord more easily. Many of the common sounds in jazz can be found using this method and you’ll find that often chords can be associated with a whole myriad of different scales.

Up until this point, we have already started to associate certain extensions/alterations with scales but maybe not so obviously. By using a major scale earlier as a jumping off point, we now know the different chord qualities associated with all seven modes of a major scale. For example, all major scales can be associated with an accompanying maj13 chord (with or without the 11th). Going further, all dorian modes can be associated with a min13 chord and so on. With this in mind, we can now open up other scales that exist and start unpacking what extensions and alterations naturally occur within them.

This theory, when I was introduced to it, changed my entire perspective of jazz. At university I took a class nicknamed "scale jail." Most students hated it, and I can see why. We looked over all of the commonly used scales in jazz and had to be assessed on them weekly. When you play scales on any instrument it can be quite tedious, similar to practicing grammar or the alphabet—something necessary to understand how to put words together, but not necessarily the most enjoyable thing to do.

While taking this class, I was also enrolled in arranging classes, allowing me to see chord scale theory through a writing lens rather than an improvisation lens like the other students. This perspective was hugely beneficial because it expanded my harmonic knowledge and helped me see logically why they were used. In a similar way to how you might improvise and experiment with chord scale theory, I did that through my arrangements.

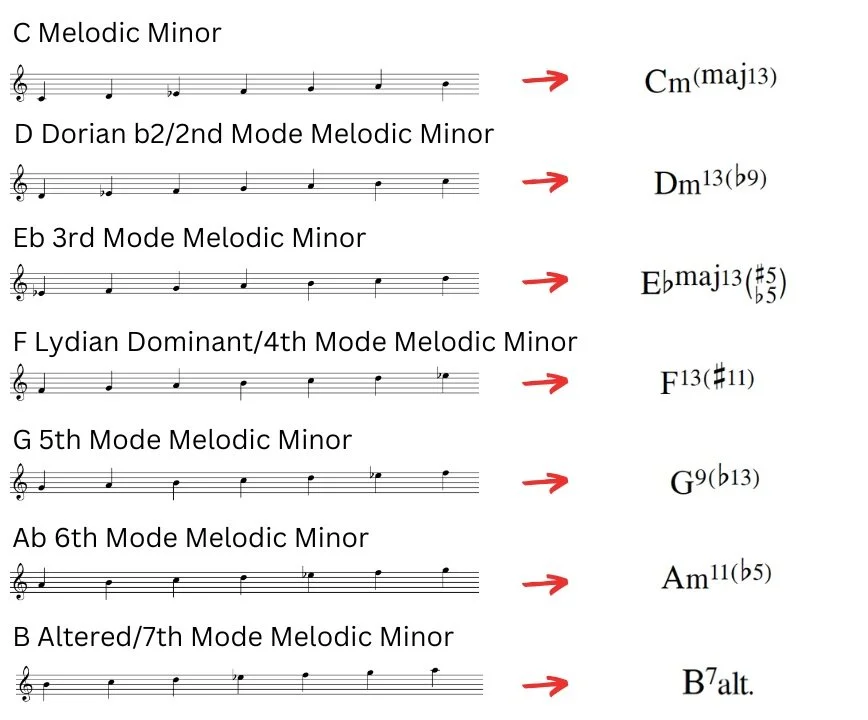

The exciting aspect of this was that it introduced me to many different scales and sounds that I was previously unaware of. Other than just your major scale, which is generally a jumping-off point for most music theory lessons, it introduced me to the modes of the minor scales. Many of you may already be aware of this, but it was new to me when I joined the class. At that time, I thought the modes were just the ones from the major scale: Ionian, Dorian, Phrygian, etc. However, there are also modes associated with the minor scale, specifically the modes of all three minor scales (natural, harmonic, and melodic).

Unlike the major scale, the naming convention varies depending on who you talk with. When I learned it, sometimes they would call a chord something like "Dorian b9," basing it off what the original major mode might be with some alteration. In other instances, they would simply say it’s the “second mode of the melodic minor scale." To keep it simple, I will refer to them as the first, second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth, and seventh modes of the associated scale. If you want to draw connections from that, you can. In some cases, I will mention specific names that are more commonly used by musicians just so you are aware of the popular options. A great example of this would be Lydian dominant, which is the fourth mode of the melodic minor scale.

To expand upon what we already have covered with the major modes, let’s take a look at the minor scales and the associated modes of each variation. We’ll start with the easiest of the three, the natural minor scale. As it shares all of the same notes as its relative major scale the associated modes are simply the exact same as the relative major. The only difference is the set of modes begins on aeolian instead of ionian.

Now the other two minor scales offer new options that we haven’t seen before. Both scales are similar, but due to the variation in the 6th we get a few interesting differences when it comes to the accompanying extensions and alterations. Like we did earlier with the major scale, here are the extensions and alterations which naturally occur in C harmonic and C melodic minor, as well associating each mode with the accompanying chord.

Exploring Non-Diatonic Options

By simply including the harmonic and melodic minor scales, we have accessed a much larger array of extensions and alterations which occur diatonically. However, we can go further and look at other scales to find even more options. Due to the extremely vast amount of scales found around the world, it would be impossible for me to cover everything, but I will discuss a number of scales that I use often and that are commonly associated with jazz. If you're a fan of impressionist harmony, you'll know that many of these were created and used in the 1800s and early 1900s by composers like Debussy and Ravel. However, they also have a place in jazz through musicians such as Art Tatum who were inspired by the impressionist composers.

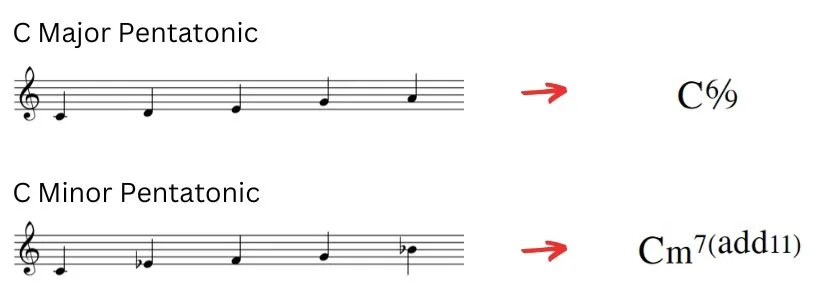

So, what are some of these scales? To begin with, let's look at the pentatonic scale. This is an amazing scale as it features no dissonant intervals and is highly versatile. It can be used as a tool for beginner improvisers but has also been used in modern jazz by artists such as Wynton Marsalis. There are two primary variants, the major and minor pentatonic scales. The major version features the notes of the major scale but omits the 4th and 7th degrees, removing any minor 2nd rubs from the scale. As a result, you can stack the notes in any configuration and it won’t have any dissonance. The minor pentatonic is similar but removes the 2nd and 6th degrees of the natural minor scale.

Looking at the pentatonic scales through the lens of chord scale theory, we see that the major pentatonic is associated with a maj6/9 sound and the minor with a min7(add11) sound. Both of which can be found otherwise by vomiting certain color tones from major and minor scales, but understanding the accompanying chords can be useful if you are wanting to use the pentatonic as a writing device.

If we add an extra note to these scales, we arrive at what many refer to as the blues scale. I don't particularly like to think of the blues scale as an actual scale, rather, I prefer to think of blue notes and how you can add them to any scale to achieve a bluesy sound. Blue notes add tension and stem from a history of American slavery, which gave rise to work songs and gospel music. Vocal styles incorporated tones that existed between the minor and major third, which created slightly dissonant rubs that evoked the feelings of those people during that time.

Because the slaves could not play instruments and had their African traditions taken away from them, they were only able to sing, which led to the blues tradition. The blue notes we think of today are the minor 3rd, the b5, and the minor 7th. If you want to capture the sound of the blues, you can start adding these notes into many contexts. However, what usually happens is that they get added into the minor pentatonic sound, particularly the flat 5, and that’s what we call the blues scale.

It's challenging to capture these blue notes in chord symbols as sometimes you’ll create unwanted clusters by writing them as extensions or alterations. Generally, I would suggest that unless there is a specific note, like the minor third on a dominant chord which we could think of as a #9, most of the time it’s better to omit them from a chord symbol altogether. If you wanted to add a blue note into the music but not into the chord symbol, you’d simply add it to a written melodic line.

Up next are six-note scales. Specifically, the augmented scale and the whole tone scale. Both of these are symmetrical scales, which means that the internal structure of the intervals are built in a symmetrical pattern that repeats. For example, the whole tone scale gets its name as it is constructed entirely of whole tones. By building whole tones beginning at C, it takes six notes before we land at C again and repeat the loop. The same thing happens with the augmented scale, but with a combination of minor 2nds and minor 3rds to create a symmetrical major 3rd structure. As a result, we obtain some unique extensions that only occur from these scales.

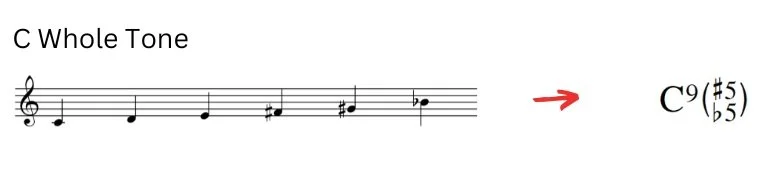

If we take a closer look at the whole tone scale, we can split the six notes into a fundamental triad and a number of extensions and alterations. The C, E, and Bb give us a C7 sound, with the F# and G# being seen as a b5 and #5, and the D being the 9th. As a result, we get a C9(#5b5) sound which is the first place we’ve seen a dominant sound with an altered 5th and no altered 9ths.

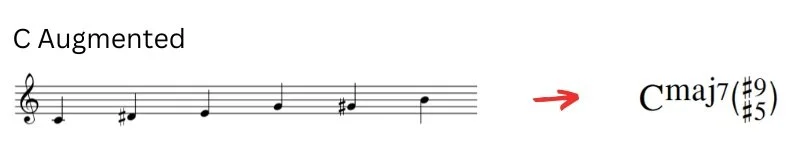

Let's look at the augmented scale. Unlike the whole tone scale, the six notes move in a minor 3rd minor 2nd pattern which results in a completely different sound. The C, E, and B give us a Cmaj7 sound, with the D# being the #9. Now this is where things get tricky. As there is both the G and G#/Ab, what typically happens is that people omit one or the other, resulting in the chord symbols Cmaj7(#9) or Cmaj7(#9#5). However, you can include both notes by thinking of the G#/Ab as a b13th, giving us the unusual chord symbol Cmaj7(#9b13). I can’t say I’ve ever seen this one out in the wild as it adds quite a lot of spice to a maj7 chord, but it is still a valid option and one worth knowing.

Finally we have arrived at my personal favorite non-diatonic scale, the diminished scale. It’s an eight note scale with two variations which is built upon a symmetrical pattern of minor thirds. If you are familiar with the diminished chord that features stacked minor 3rds, both variations of the diminished scale derive from this same symmetry. One variation splits the minor 3rd by a whole tone followed by a semitone/half-step, with the other flipping the orientation. As a result we get the shorthand W ½ and ½ W (pronounced whole-half and half-whole).

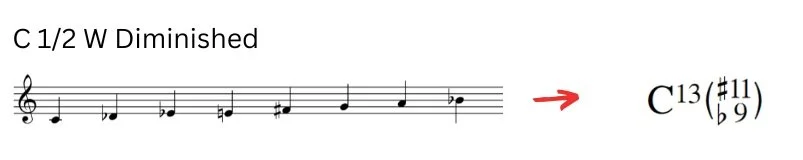

The ½ W variation is particularly versatile for jazz and may be one of the most frequently used scales since the 60’s due to the number of associated chords that come with the scale. For example, we can create a minor triad, a major triad, a dominant seven triad, or a diminished triad built off of the root note. With all of the other notes available in the scale, you can imagine that there are plenty of different chord combinations to use. For the most part, the one that gets the highest rotation is the Dom13(#11b9#9) chord which is the only way to stack the eight notes so that you can use absolutely all of them in one chord. It’s a wonderful chord with significant dissonance and sophistication, and one which was favored by the great arranger Thad Jones.

Moving to the W ½ variation, the most commonly associated chord with the scale is simply the whole diminished chord with a major seven. While still a great sound and useful, the W ½ is not as adaptable as the ½ W due to the available notes. As such, the ½ W receives considerably more playtime in jazz circles.

Adding Color Into Your Chord Progressions

Before diving even deeper into jazz harmony, now seems like a good time for a quick recap. Up until this point we have looked at the modes of the major scale, the modes of the various minor scales, the pentatonic, blues, augmented, whole tone, and diminished scales, as well as the associated extensions and alterations which accompany them. Hopefully you have started to draw connections between certain sounds and scales, and as such might be starting to think how to apply color tones into a chord progression. Fortunately, to do this it’s rather simple!

Building off of the idea of functional harmony and creating progressions using the chord resolution formula, all we have to do is now implement extensions and alterations. To keep things simple, start off with a progression in a major key and add the diatonic extensions/alterations to each chord. For example, in C major you could add a 9th, #11th, or 13th to the IV chord or perhaps an 11th to the ii chord.

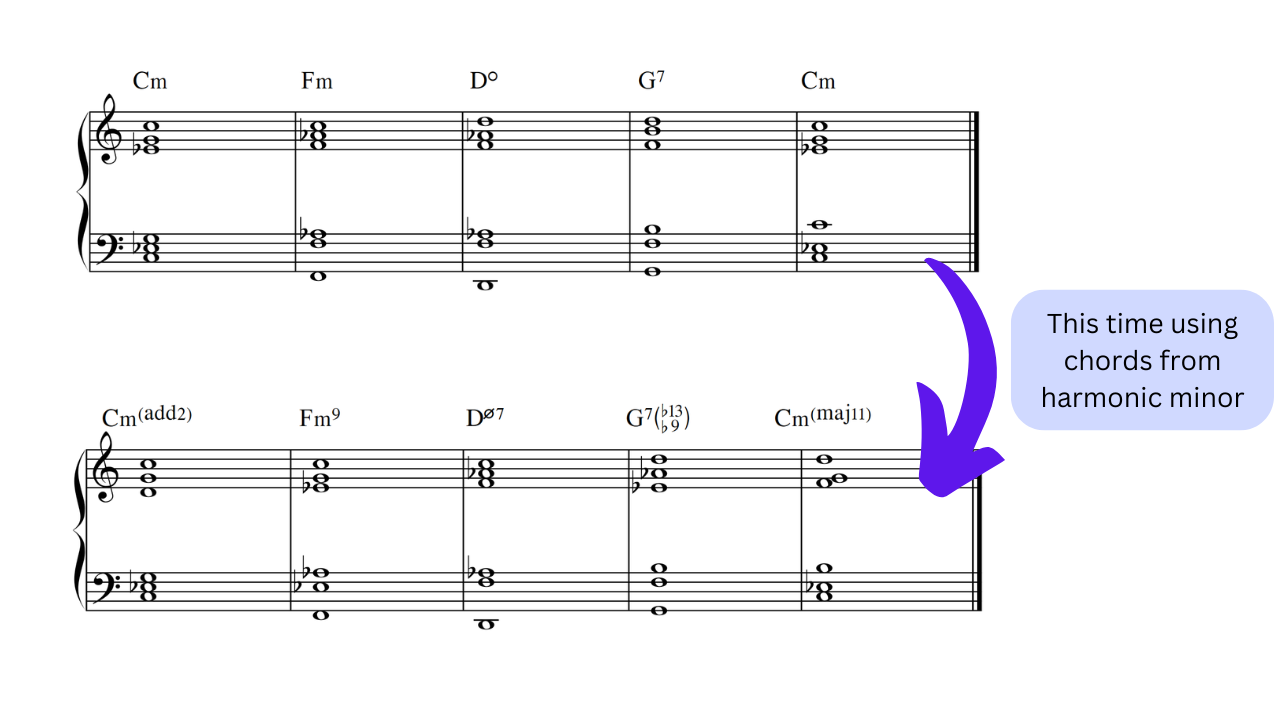

Now let’s do the same but with a minor progression. Remember that you can include minor 9ths or you can avoid them depending on what you like the sound of.

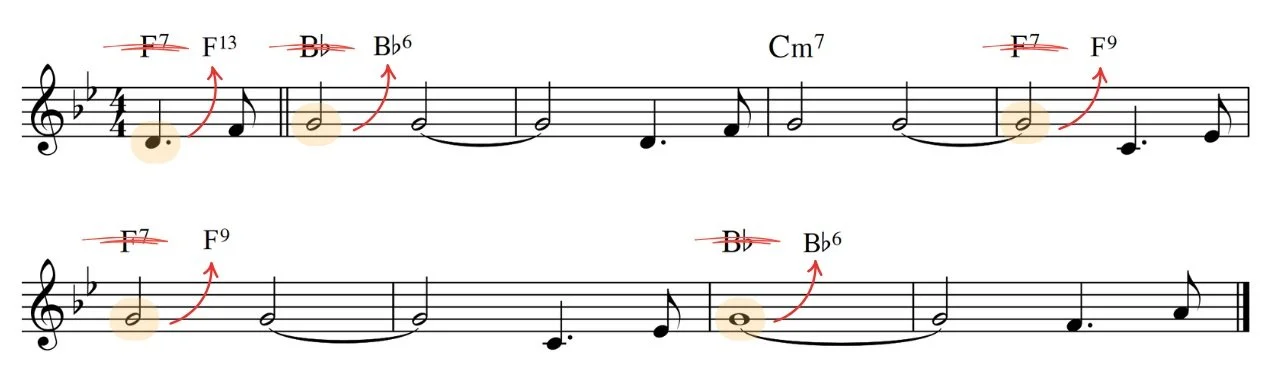

We can also look for inspiration from melodies. You may remember earlier I said that chord scale theory helps us associate chords from scales, but it also works in reverse. This can be quite useful when we look at songs and want to add color but want to also maintain the original feeling of the harmony. For example, if we look at the melody of the popular standard Mack the Knife, it implies a number of color tones that aren’t in the accompanying harmony. Specifically, in the first bar the melody implies a 6th, and in bar 4 it implies a 9th. Using this information we can change the chord symbols to more accurately represent the added notes of the melody.

With those techniques under our belt, it’s time to look at applying the chords associated with non-diatonic scales, but to do so, there is one last trick up our sleeves which will really blow everything out of proportion in a good way.

The Power of Interpretation

What I’m about to unveil may be the single most impactful insight I’ve been taught when it comes to jazz harmony. I came across the idea sometime while taking multiple theory classes and as a result it has completely changed how I look at chord changes. So far the status quo has been to think about harmonic progressions as being functional, following a set of resolutions that come from the bias of the major scale. However, this is only one way to interpret chords and write chord progressions. Without changing the path of resolution that the chord resolution formula provides us, we can also access any extension/alteration combination at any point if we so choose. The key to doing so comes down to interpretation.

During the summer of 2014, I was taking my last music theory class for my degree. Due to it being in summer it was a small class that met every weekday for 3 hours at a time. Most of my peers hated it for this reason, but I loved every moment as I could bombard the unlucky professor with as many questions as possible and come back each day with a new set of questions based off of the previous day's content. While in the class the professor asked us to analyze a certain excerpt. I can’t remember which particular composition it was but I do remember that my analysis differed from the rest of the class and even the professor. Not being shy of attention, I raised my hand and boldly exclaimed that I had a different result to what the professor had found. To my surprise, the graduate teaching assistant thought my analysis worked well and was just as correct as the professor's answer. In the end, both solutions worked and I realized that multiple interpretations of a chord progression could be correct.

The reason I share this story is because often we get stuck thinking there is only one way to understand chord progressions. Often we follow the path more travelled, which definitely works, but can stop us from uncovering another world of possibilities. It is on this less defined path where the real power of chord scale theory lies. Where we can look upon a chord symbol, or multiple, and interpret them using more than just one scale.

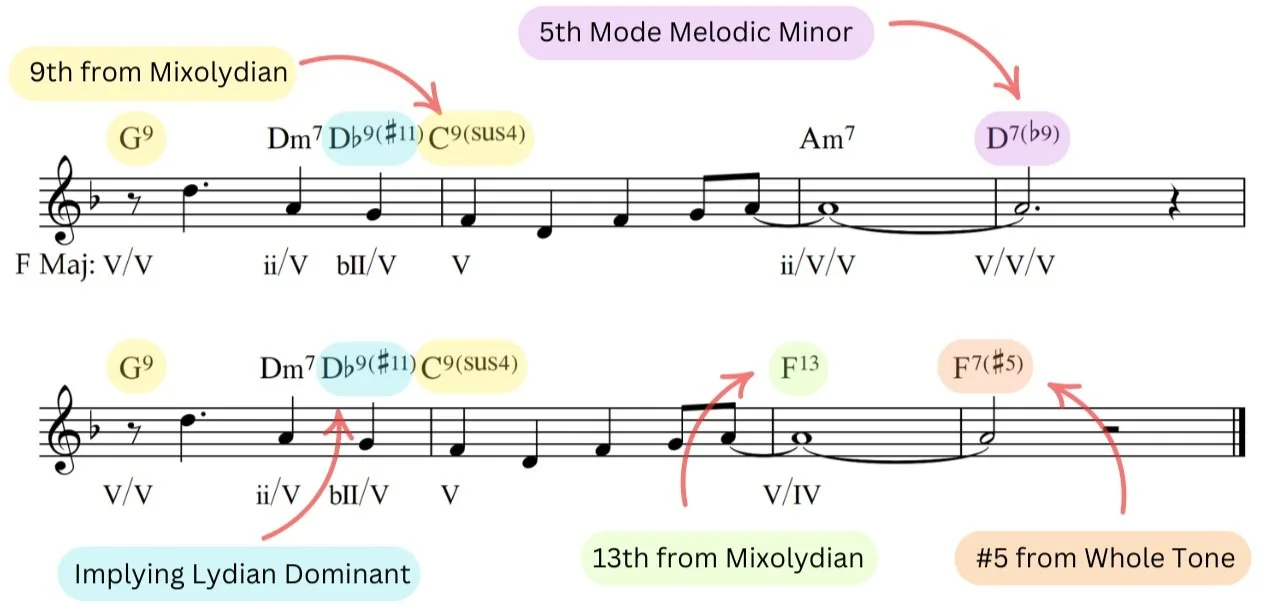

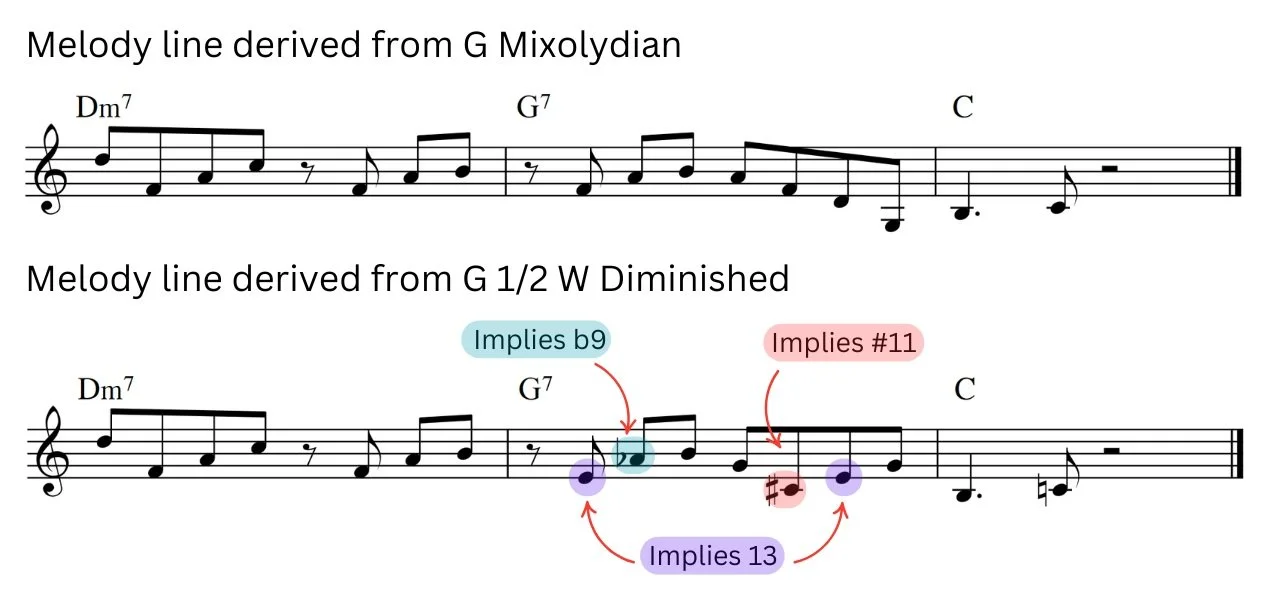

For example, if you saw a chord progression in C major and there was a G7 chord, the common path would be to interpret it as a V chord, pulling color tones from the G mixolydian mode. However, if we remove the context of the key for a moment and just inspect the chord symbol itself, it only gives four notes: G, B, D, F, and no specific indication that it has to be interpreted as the dominant chord relating to mixolydian. Instead, we could look to other scales which also have an accompanying dominant chord and use those color tones.

If you’re new to this concept that may take a few re-reads to understand but to get you there a bit quicker, I’ll unpack the example further. Instead of mixolydian which would imply G13, we could interpret it as ½ W Diminished giving us access to G13(#11b9#9), or perhaps you prefer Lydian Dominant G13(#11), or maybe 5th mode of harmonic minor G7(b9b13). As you can imagine, this is only the tip of the iceberg and it is up to you to interpret the chord however you’d like.

We as arrangers have a great deal of flexibility when it comes to how we add color to chords. Be mindful that the melody note may also remove some options such as landing on a natural 5th would likely stop you from using a chord with an altered 5th. But otherwise, now every single chord symbol can be interpreted however you like. As the fundamental chord tones are unchanged, the path of resolution will still work, meaning that the progression will feel functional. However, the extensions and alterations are free to come from whatever scale you interpret. There is no right answer, simply whatever option you think fits the situation the best.

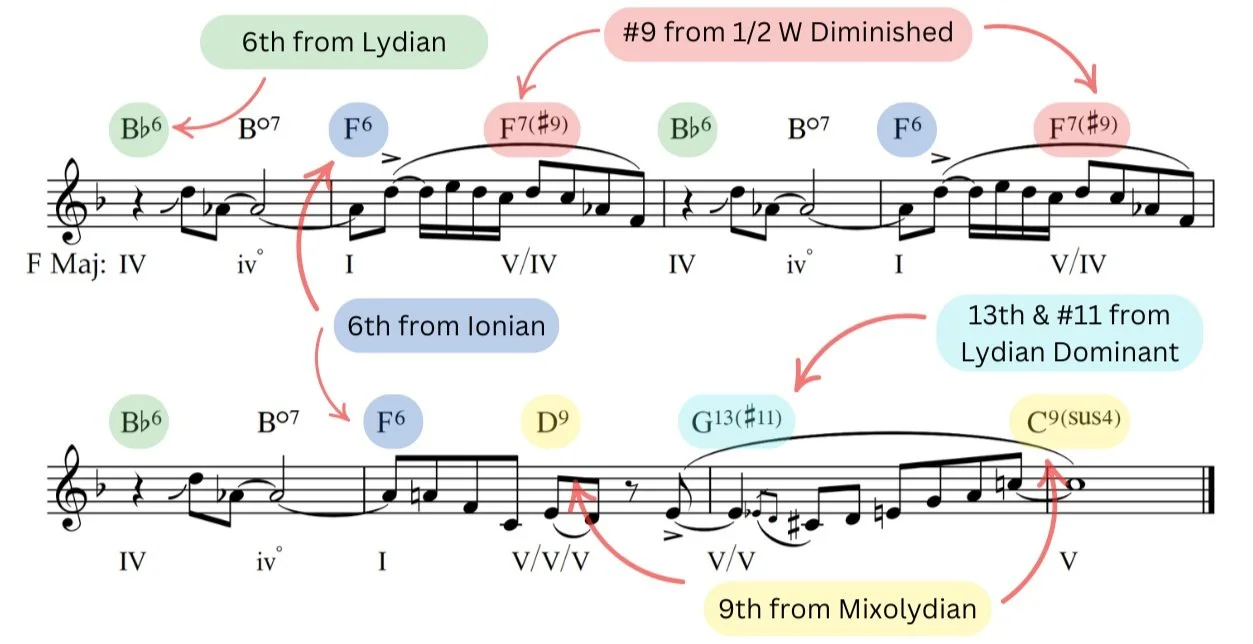

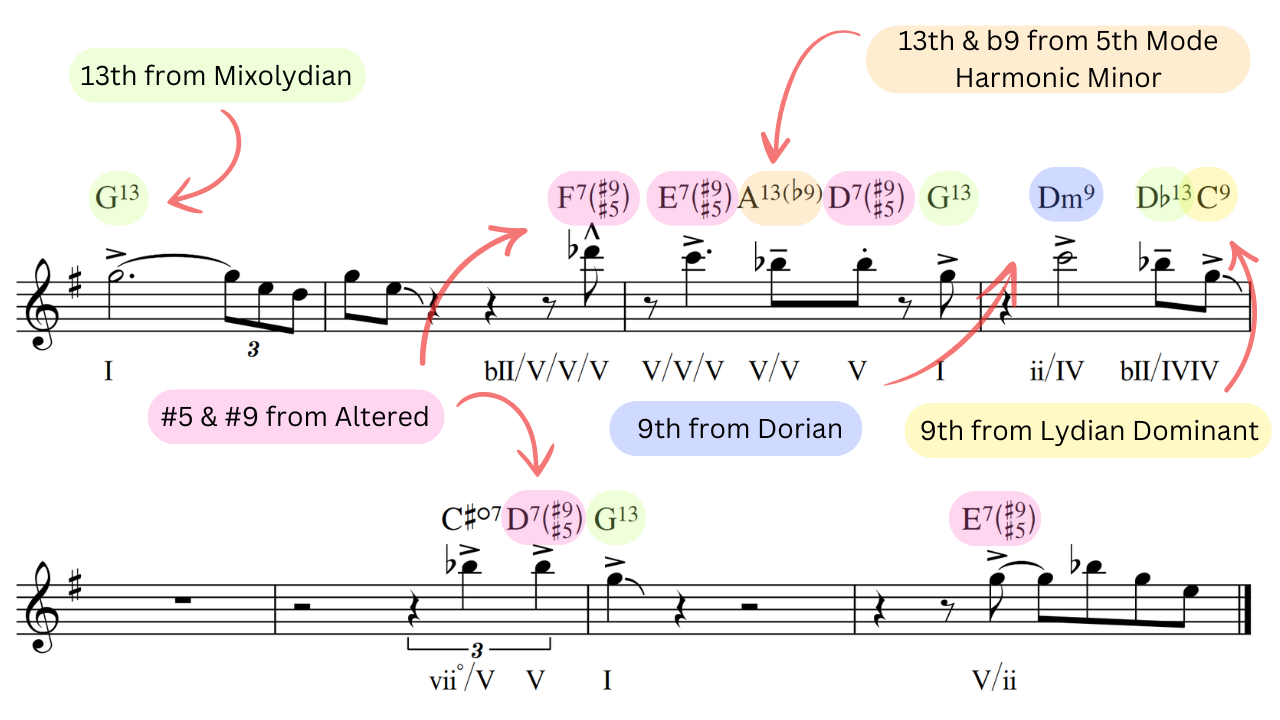

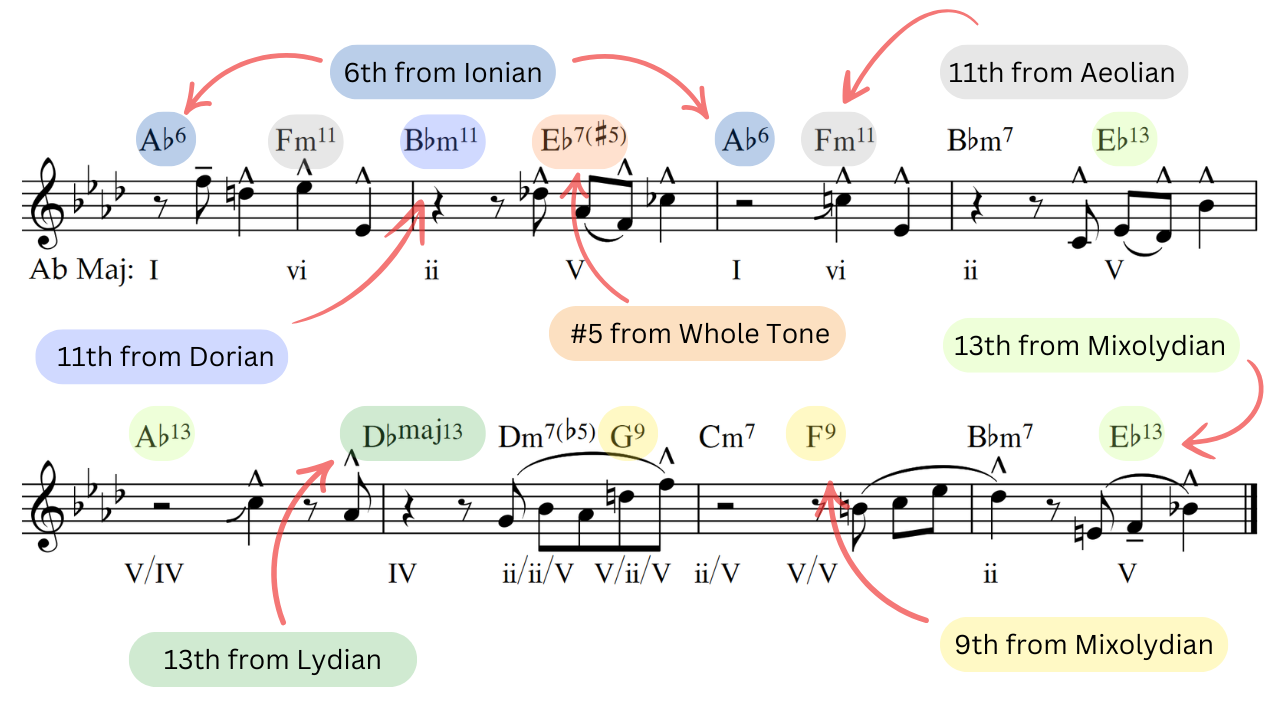

With all of the techniques discussed, let’s have a look at some examples to show you how various arrangers have made use of extensions and alterations. I’m particularly fond of writers for the Count Basie orchestra, so below you’ll find a number of different examples from writers like Neal Hefti, Sammy Nestico, Quincy Jones, and Thad Jones.

Li’l Darlin’

Neal Hefti

Hay Burner

Sammy Nestico

Let The Good Times Roll

Arr. Quincy Jones

Tiptoe

Thad Jones

Compared to any of the topics covered so far, chord scale theory can feel completely overwhelming as you now have access to every extension/alteration combination. When paired with substitution techniques, the sky is the limit. If this makes you feel anxious, remember that you don’t have to use every option just because you can. Take it slow and work out the ones you like one by one. Over time you’ll have a bag of tricks that you can turn to and you’ll have tested each and every one of them. You’ll also find that depending on the context, some color tones are more effective than others, and some are definitely to be avoided. If you enjoy problem solving and trying new combinations of chords, then you’re going to love experimenting with this.

One side note before concluding this technique. Chord scale theory is also a wonderful tool for improvisation and creating melodies. We have primarily looked at it from the standpoint of creating colorful chord options, but you can also think of it as a powerful tool to create unique melodies. Using the previous example, let’s say your progression has a G7, you could write a melody line that follows any one of the interpretations we listed and it would work just fine. If you look to apply this in your improvising, the only difference is that the whole process is done in real time, something I find a whole lot more difficult.

Controversial Chord Symbol Opinions

So where does that leave us? Well we know where to find color tones and how to apply them but we need to make sure we can accurately represent those sounds through the chord symbols we write. Unlike the fundamental triads and 7th chords which most people are familiar with, when it comes to extensions and alterations, things can become quite confusing and there are a few different interpretations.

However, first let’s look at the standard conventions that all jazz musicians agree on before we stir the pot a little. When extensions are used in chord symbols they follow a strict set of rules which can be applied to all chord symbols regardless of the chord quality. The numbers representing each extension can exist in one of two places if being used, directly after the chord quality, eg. Cmaj13, or in a set of brackets, eg. Cmaj7(13). Both mean two different things even though they sound quite similar. When directly following the chord quality it implies that all extensions below the one written can be played. For example, Cmaj13 implies that the 13th, 9th, and major 7th can be played. As the 11th creates a minor 9th on this chord it would usually be omitted or altered unless specified otherwise. Whereas when using a bracket it means that only that specific extension or alteration is played. For example, Cmaj7(13) implies that it would be a Cmaj7 chord plus the 13th with no other extensions. Sometimes this will also be seen as Cmaj7(add13).

When we write extensions, they always get interpreted as if they were in relation to a major scale. What this means is that if you had a C minor chord with a 13th, it wouldn’t be Ab even though in C natural minor there is a b6th, it would be an A. Out of everything I’ve come across in my years teaching, this seems to be where newcomers get the most confused. Fortunately, looking at chords in this manner does make everything much easier as you only need to remember that extensions and alterations based off of the major scale. The chord quality text will only impact the fundamental notes (root, 3rd, 5th, 7th) and not the extensions (9th, 11th, 13th).

The confusion continues with the naming system for alterations. Specifically those that are enharmonically the same. For example, if you have a b13, it is enharmonically the same note as the #5. The same can be said about the #11 and b5. After many years interacting with jazz musicians out in the wild, I’ve found people fall into two camps. Either they think the enharmonic alterations can be used interchangeably or that they imply different sounds. Based on who I learnt from, I fall into the second camp and as such, I’ll unpack why I think they work this way below. Just remember that at the end of the day, it’s just a naming system for notes and it doesn’t really matter. What matters more is the music sounding how you want it to and that musicians understand your intention. I’ve had far too many heated arguments around this topic, which in hindsight is quite stupid.

If we look back at the non-diatonic scales above, we see that the accompanying chord symbols are spelt in specific ways. For example, the ½ W Diminished has a #11 not a b5, and the whole tone has a b5 and #5 not a #11 and b13. Why is that? It’s because they are implying a specific structure of notes. Generally, if you have a natural 5th in a scale there is a rule that you can’t have an altered 5th, and the same goes with all other notes too. But what happens if you really want a 5th right up against a #5th or b5th? Well for one, you could ignore the general rules, but if you wanted to abide by them you could make that happen by altering the 11th or 13th. That way you could have a #11 and a 5th next to each other which would sound the same as a b5th and 5th being played. Similarly, you could have a b13th and 5th next to each other.

The main reason I try to be specific about these enharmonic alterations is because in diatonic music they often refer to a specific interpretation I want the musicians to follow. If I write out a detailed chord symbol such as C13(#11) I want them to interpret it as being a lydian dominant sound. Or if I write C7(b9b13) I want them to know I mean 5th mode of harmonic minor and not C7(b9#5) which I would associate with 7th mode of melodic minor.

There are also multiple shorthand symbols people use. Some people like the chord quality to be fully written out such as Fmajor7, with others preferring options such as Fmaj7, Fma7, FMA7, FM7, as well as F△. The same can be said with minor chords with options including Fminor7, Fmin7, Fmi7, FMI7, Fm, and F-. When adding a flat 5 to a minor 7 chord, sometimes you’ll see people write Fmin7(b5) or FØ7. Augmented chords can be written in one of two ways either Faug7 or F+7. Finally, some people write alterations as # and b, whereas others prefer + and -, eg F7(#5b9) or F7(+5-9). All of these options are completely legitimate and I would suggest using whatever the musicians you work with are most comfortable with.

Remember that whichever way you look at writing chord symbols, the most important aspect is always the music and that the musicians can interpret your intention accurately. Talk with the people you are writing for and make sure you are on the same page with chord symbols. That way no matter how you notate them, they’ll be played how you intended.

The Takeaway

With all that said, you should hopefully have a good idea of how jazz harmony works, at least the diatonic side of it. Although we started to explore the non-diatonic world a bit, there is a whole lot more that can be discussed which will have to be saved for another time. However, there should be more than enough here to help you write music that fits into the jazz world. We’ve covered a lot of ground and introduced a lot of information, and I know when I was introduced to it I was completely overwhelmed. But to make things a lot simpler, just remember that the key takeaway from this whole page is that to make anything sound “jazzy” you just need to add color tones. Everything else is just extra knowledge.

Now that the world of extensions and alterations has been unpacked it’s time to move into more advanced types of substitution. Similar to how we examined modal interchange and functional substitution for diatonic harmony, there are a few extra fun substitution methods we can use that will provide even more color. Namely, we will discuss tritone substitution, which is a fairly common technique, as well as Two fantastic methods which will bring even more color to your progressions and change how you approach reharmonization.