A Game Changing

Substitution Technique

Jazz harmony has to be one of my all time favorite categories of arranging. I am a self confessed music theory nerd and every time I am introduced to a new technique I usually spend days geeking out about it. And the topic of this particular resource is no different. In fact, I have not only experienced what it’s like to get my mind blown by one of the techniques discussed, I have also seen it blow the minds of many of my students. So what am I alluding to? Reharmonization, and not just modal interchange or functional substitution but a completely unique way to substitute dominant chords. Specifically two techniques that have redefined how I have personally approached writing chord progressions. Up first is something that is a bit more common but later on things start to heat up with a technique most people have never heard of.

I was introduced to the first technique when I was 18 years old while preparing for my bass audition for the University of North Texas. My teacher at the time was the fantastic Melbourne based bassist Kim May. We were looking at the standard Autumn Leaves and unpacking ways I could add more interest into both my walking bass lines and improvisation. One way he presented was through tritone substitution, a technique that originated in the bebop era of jazz and has since become a staple in the vocabulary of most jazz musicians. Kim presented the technique as a method for adding extra dissonance and color within functional harmony. And you know what, it was love at first sight. As soon as I learned it, I applied it to every dominant chord for at least the following year or two. When I began arranging, it quickly found its way into my compositions. Why? Because it sounds fantastic and is an excellent way to change listeners' expectations while maintaining the music's functionality.

A year later I was lucky enough to be in a position to teach someone else the technique. Coincidentally another bass student of Kim’s. The student asked me about ways to add color to the chords he was writing, and when I introduced him to tritone substitution he experienced the same light bulb moment that I had. It is truly a game-changing technique, which produces far more bang for its buck.

Before we jump into tritone substitution I should warn you that a lot of the content below is built off of a number of different techniques previously covered. If you aren’t familiar with how functional harmony works, have a read of this resource, and if you don’t know much about extensions, alterations or chord scale theory you may want to look at this resource.

The Power of Tritones

So, what is tritone substitution? Unlike the previous styles of substitution we have examined, such as modal interchange and functional substitution, which involve swapping out chords from parallel keys or those with similar functions, tritone substitution focuses specifically on dominant 7 chords. It is highly popular in jazz as it adds a considerable amount of chromaticism and is quite easy to understand. Simply put, to use tritone substitution all you have to do is substitute a dominant 7 chord with one located a tritone away. For example, if you have a G7 chord, you can substitute it with a Db7 chord.

At first glance, this may seem quite odd but there is logic behind the madness. To understand the technique, we need to examine the note makeup of each chord. G7 consists of the notes G, B, D, and F, with Db7 made up of Db, F, Ab and Cb. If you look closely you will notice that both chords share two notes, specifically the B (Cb) and F. These notes define the dominant quality of the chord, but more importantly create harmonic tension and chord functionality. As the notes are already separated by a tritone, by substituting the root note to one a tritone away, the only thing that happens to the 3rd and 7th is that they are inverted. Ultimately allowing the chord quality and functionality to be maintained while introducing other color tones.

Now let’s have a look at the other two notes, the Db and Ab. If we were in the key of C major where G7 is the V chord, both of these substituted notes would be outside the key signature and help introduce a considerable amount of color. They also introduce two more semitone/half-step resolutions, with the Ab wanting to resolve to either the G (5th) or A (6th/13th) and the Db wanting to resolve to the C (root) or D (2nd/9th). As a result, tritone substitution creates a much stronger pull toward whatever diatonic chord may come next.

It should be noted that this technique only works for dominant chords due to the tritone relationship between inner chord tones of the 3rd and 7th. If you were to apply the technique to any other quality of chord it would lead to a different result which would not maintain the functionality of a progression. That doesn’t mean you can’t experiment with the idea to come up with fun other chord ideas, it just means that those chords won’t be able to be substituted in a functional manner.

As tritone substitution only works with dominant chords it may seem somewhat limited in application compared to other substitution techniques like modal interchange. However, all it takes is one look at how popular dominant chords are in jazz to realize that the technique can be used in an almost limitless number of places. No matter how a dominant chord is placed in a progression, it can be reharmonized with tritone substitution.

If you want to go a step further and combine the technique with chord scale theory, you now have doubled the amount of ways you can interpret a dominant chord. Not only do you have access to all of the scales which work over the original chord, but you also have all of the scales which work over the new chord.

Li’l Darlin’

Neal Hefti

To me the best element of the tritone substitution is that it can be quite a surprise within a progression. In just one chord you can add so much chromaticism that it can be quite shocking which can be used to break the monotony of a repetitive form. Not to mention, it just sounds cool!

Stepping into the land of extensions and alterations, we can create interesting sounding chords by combining both the original and substituted dominant chords together. For example, you can take some notes from Db7 and use them as extensions over G7. The Db could serve as a b5 or #11, while the Ab acts as a b9. Alternatively, if Db7 was your base, you could use the G as a b5 or #11, and the D as a b9.

Tritone substitution is a powerful tool in an arrangers kit. When combined with other substitution techniques, you can create progressions which sound completely different to the original but still maintain functionality. To show you just how extensive you can use tritone substitution, here is an example of where I stretch the 12 bar blues a bit. Yes it can be taken much further but I wanted to maintain some level of music restraint.

Symmetrical Substitution

Aside from tritone substitution, there is actually another way you can substitute dominant chords, one which encapsulates tritone substitution into a much larger technique. I was originally introduced to this sometime in 2014/2015 when I was learning arranging under Rich DeRosa. He described how you can substitute dominant 7 chords through symmetrical intervals, specifically the minor 3rd and the major 3rd.

Rich first looked at the minor 3rd and demonstrated the relation between a dominant chord and the ½ W diminished scale, noting that starting on the root note you can interpret the notes of the scale to form a dominant 7 chord. Because the scale is symmetrical by minor 3rds, he revealed that a dominant 7 chord appears in four places, specifically built on either the root, m3, b5, and 6th degrees of the scale. In other words, on every note spaced a minor 3rd apart from the root. With this idea in hand he then revealed that each of these dominant chords could be interchanged with one another. For example, if you started with a G7, by moving up in minor 3rds you also have access to Bb7, Db7, and E7. With each chord being able to be substituted with one another.

Similar to how we broke down the internal workings of tritone substitution, it is necessary to look a little deeper into the chord tones of each option to understand how this works. Up first is Db7, which if you notice is actually located a tritone away from G7 and thus works exactly the same way as a tritone substitution. However, both Bb7 and E7 work a little differently.

The notes of Bb7 are Bb, D, F, and Ab, which in the key of C major (the home key of G7) create some different functional pulls than the original G7 chord. To best understand where the tension in the Bb7 wants to go, let’s have a look at how it would resolve to a I chord in C major. The Bb would want to resolve down to the A (6th/13th), the D could stay put (2nd/9th) or move down to the C (root), the F would resolve down to the E (3rd), and the Ab would resolve down to the G (5th). Although we lose one of the pillars of the dominant resolution between V-I being B going to C, we pick up two other semitone/half-step resolutions which help it maintain a sense of resolution. However, if you take a step back and look at a Bb7 to Cmaj resolution, this can already be achieved through the chords of the natural minor scale which includes a bVII dominant chord diatonically. Symmetrical substitution is just another way of getting to the same solution.

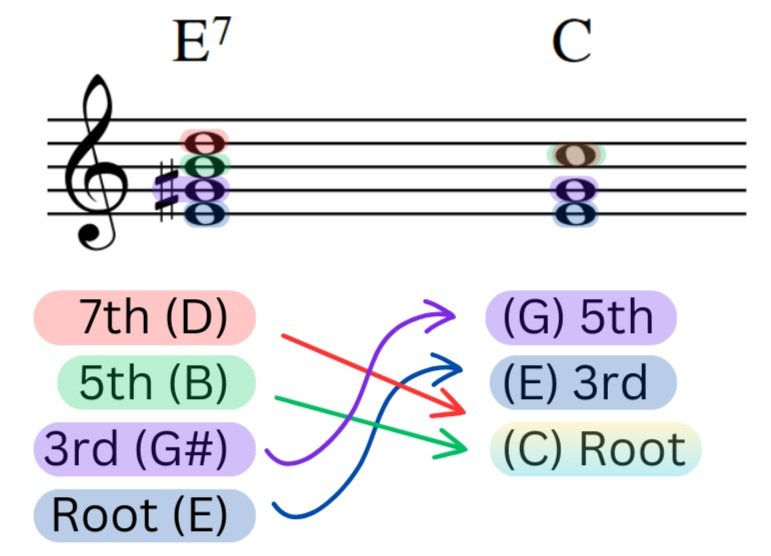

Moving to the last option E7, we already know this will work as it is a tritone away from Bb7. However for interest's sake, let's still have a look at how the chord tones would resolve to a I chord. The E would stay put (3rd), the G# would either go up to A (6th/13th) or down to G (5th), the B would go up to C (root), and the D would stay put or go down to C (root). Like the previous example, E7 maintains one of the functional resolutions from the original G7 chord but then replaces the others with new notes. Fortunately, it still functions as a valid substitution as there are enough semitone/half-step resolutions between the chords.

Switching gears away from minor 3rd relationships, this same type of substitution works through the symmetrical nature of major 3rds. Unlike minor 3rds which can be justified through the ½ W diminished scale, major 3rds have no specific parent scale which imply dominant chords. If we look at the augmented scale for instance, the implied chord is a Maj7 not a Dom7. However, the substitution technique still works due to the resolutions of the internal notes.

Starting with G7 we have access to two other chords thanks to the symmetry of major 3rds, specifically B7 and Eb7. In a similar manner to how we broke down each of the previous chords, here’s how both of these options resolve to a I chord in the key of C major. For B7, the B resolves to C (root), D# resolves up to E (3rd), F# resolves up to G (5th), and the A can remain the same (6th). This creates a unique sound because, unlike the dominant chords drawn from the minor 3rd, the chord tones of this particular substitution want to resolve upward instead of downward.

Continuing on with Eb7, the Eb wants to resolve up to E (3rd), the G stays the same (5th), the Bb resolves down to A (6th/13th) and the Db resolves down to C (root). These semitone/half-step relationships illustrate a shift away from functional harmony as they only sometimes maintain the same key notes that the original dominant chord used yet still give a sense of resolution. It marks a new type of thought, one which is broader but helps justify many more options outside of functional harmony. That is, to look at tension and resolution as a result of chord tone relationships more so than specific diatonic patterns. For now that is where I will leave that concept as it really only comes into play when you step out into the world of non-diatonic harmony and techniques.

As a result of the symmetry of both the minor and major 3rd, you can substitute any dominant chord with five other options and they will function properly. Using G7 as the original chord, the options include: Bb7, B7, Db7, Eb7, and E7. When I originally realized this I was amazed at how many options existed. Each feels so different to one another but they all seem to work. Here’s an example of rhythm changes using some of the symmetrical substitution options available.

The Takeaway

Hopefully I’ve been able to introduce something new to you when it comes to jazz harmony. Both tritone substitution and symmetrical substitution blew my mind when I first learnt about them, and as a result they both get heavy play time in my arrangements. Like anything, take your time in understanding how the techniques impact the music and what sort of feelings they create. That is far more important than the techniques themselves.

Going on from here I would suggest exploring the world of non-diatonic harmony. There are countless valuable techniques to be looked into that will drastically change the chord progressions you write. For now however, you’ll have to wait until a later time for me to write about those techniques!