What To Do With

Non-Chord Tones

Oftentimes when we try to harmonize a melody there are notes which don’t quite fit with the accompanying chord progression. That may be because they don’t exist within that chord or simply because we don’t like how they sound. In music circles we call these particular trouble notes non-chord tones and it can be hard to know exactly what to do with them. The last thing you want is to be taken out of your workflow by a weird note that you can’t find a good voicing for.

When I started dabbling with arranging as an 18 year old, I didn’t have a clue how to voice let alone know what a non-chord tone was. The only thing I knew was if the chord progression said Cmaj7 then those were the notes I should be using when harmonizing a melody line. It didn’t matter what the melody note was, the harmony notes were always going to be some sort of combination of C, E, G, or B. As you can imagine, the music I wrote wasn’t that harmonically compelling.

Shortly after, I decided to pursue private arranging lessons in anticipation of an arranging class I had signed up for in the coming fall semester. The lessons marked my first step into formal arranging tuition and I was lucky that a doctoral student by the name of Aaron Hedenstrom was happy to take me under his wing for a summer. Aaron was my first official arranging teacher and introduced me to so many awesome techniques while also being extremely patient with my lack of ability. I definitely lucked out big time. Although a lot of the content he told me has now become a blur over the years, the first lesson was one of those epiphany moments where my whole worldview on writing shifted.

Unlike many arranging courses and teachers who begin with instrument details and voicings, Aaron chose to show me how to deal with non-chord tones. Up until then, I didn’t know they had a name, in fact I was oblivious to why they may be problematic at all. Not only did he explain what a non-chord tone was, he showed me that we can harmonize them through the use of passing chords. Immediately after the lesson I rushed back to my apartment and began experimenting with the techniques he introduced me to. I’m sure none of the results were all that great but I felt like I had somehow acquired a superpower.

Specifically, Aaron shared with me that there are five common passing chord options that we have access to as arrangers: Diatonic, Diatonic Planing, Chromatic Planing, Diminished, and Dominant. Each has a certain flavor and some can be used in conjunction with other jazz harmony techniques. I’ve also since learned that certain eras of jazz favor different types of passing chords such as the diminished option being used more in early jazz and the beginning of the swing era.

Nowadays I still love using passing chords. In every arrangement I write there is always a moment I need to harmonize a non-chord tone and I fall back on those same five options Aaron showed me. I also see them everywhere I look, whether it be in a modern arrangement written recently or in classic repertoire that has been around for close to a century. Other than complimenting other jazz harmony techniques, they are also really fun to use and experiment with. You’d be surprised how far you can stretch some phrases purely by using passing chords. I know I’ve definitely flaunted the dissonance line a few too many times.

Before I unpack exactly what Aaron showed me all those years ago, this page builds off of certain terminology and techniques discussed in other resources I’ve written. If you aren’t familiar with functional harmony, extensions and alterations, and common chord symbol conventions, I’d suggest you check out the following resources first: Diatonic Harmony, Extensions & Alterations.

Stepping Outside

To understand how to harmonize a non-chord tone we must first define exactly what one is in the context of jazz arranging, otherwise we may be setting ourselves up for failure. Fortunately in jazz, non-chord tones can be almost any chord tone that we choose, it mainly depends on how we justify our choice rather than a fixed rule that applies to everything. This level of freedom can be difficult to comprehend when learning a new technique so below I’ve used a few constraints to get us started. Don’t worry though, because by the end of the resource we will be looking at the full versatility of passing chords.

Generally speaking, a non-chord tone is any note in a melody which lands outside of the accompanying harmony. It may still be located within the notes of the key signature but is usually not seen as one of the fundamental notes of the underlying chord progression. For example, if we had a G7 for a bar, any note other than G, B, D, and F could be considered a non-chord tone.

That definition can be refined slightly further by looking at the context of a melody. Depending on the duration of a non-chord tone as well as whether it is located on a strong or weak beat, it may change how the given note is felt. For example, using the same G7 chord, if you had an A held out for a full bar it would most likely be heard as a 9th and not as a non-chord tone. Whereas if the A was a quaver/eighth note located as part of a run of notes, it would be operating in more of a passing fashion and not heard as a major component of the G7.

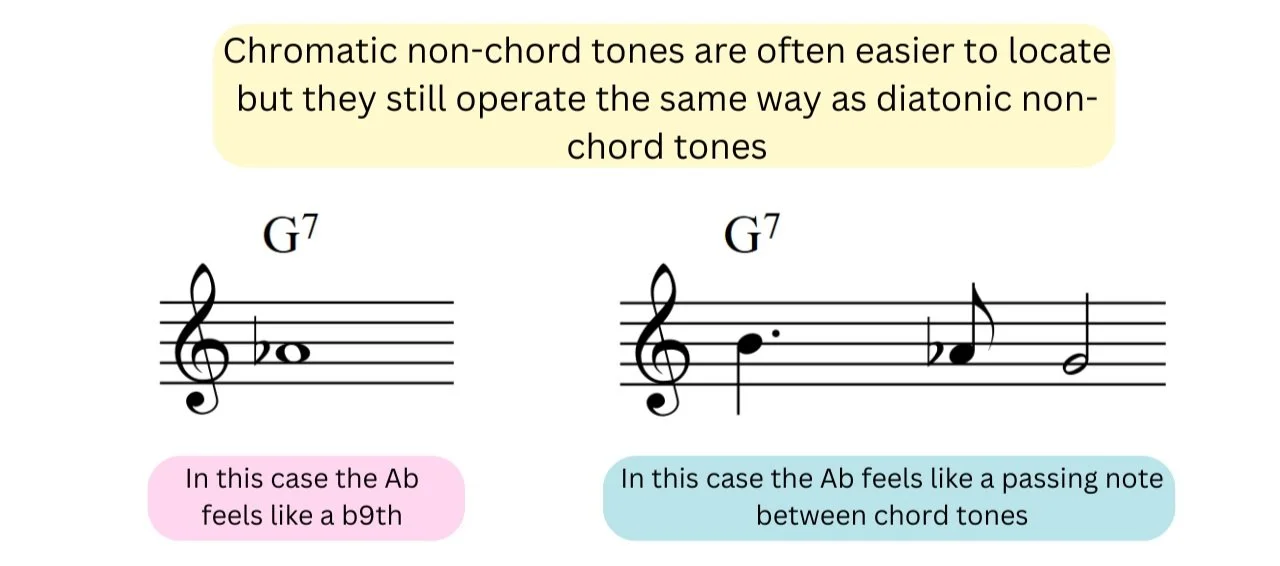

So far I’ve been using diatonic notes as non-chord tones for the examples, but non-chord tones can also be chromatic and exist outside of the given key. In fact, they are much easier to identify in this manner. Here’s another example similar to the one we just covered but with the note Ab.

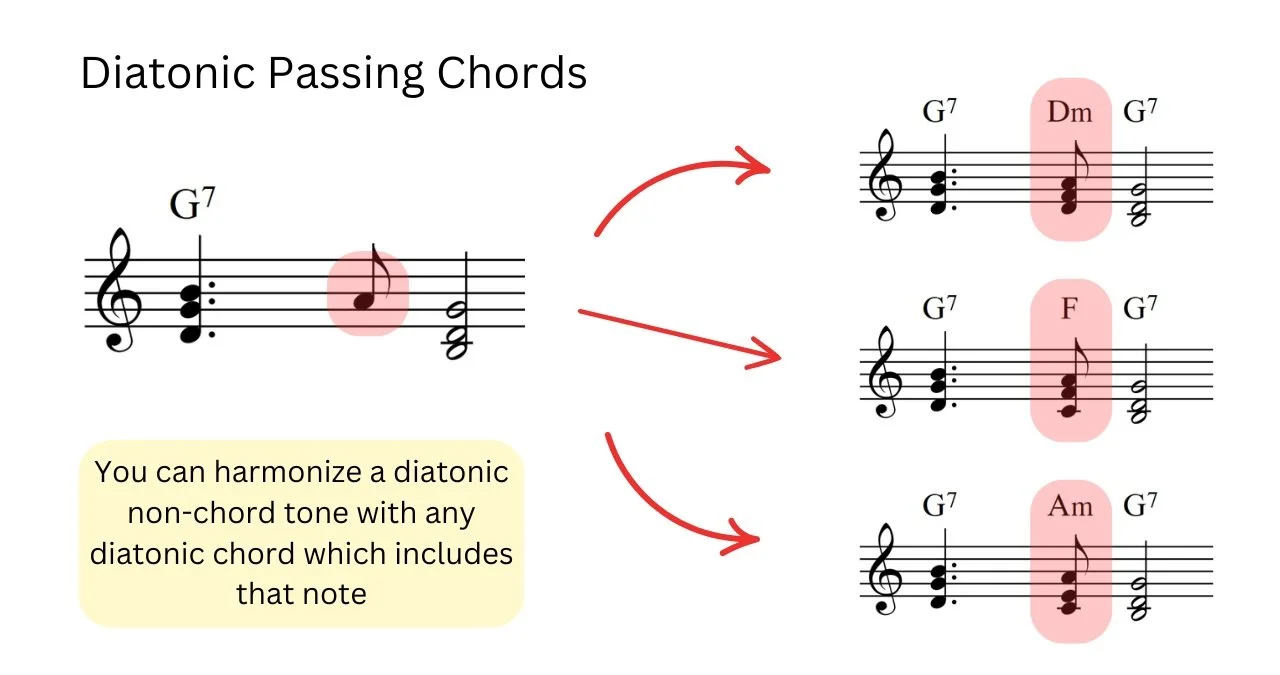

With non-chord tones thoroughly unpacked, let’s shift gears to how to harmonize them. As mentioned earlier, there are five different passing chord techniques at our disposal. Some are limited in their application to chromatic tones while others must be a part of the given key signature. Up first are diatonic passing chords, an option which often gets used without writers actually knowing about the technique.

To use a diatonic passing chord all you have to do is voice a non-chord tone with any diatonic chord which makes use of the given note. For example, in the key of C major if you had identified an A as a non-chord tone, then you could harmonize it with a Dmin, Fmaj, or Amin chord. This technique will only work if the non-chord tone is a diatonic note of the key.

In terms of how you can voice a diatonic passing chord, you have quite a lot of freedom. You can voice it in a similar manner to the notes surrounding the non-chord tone or you can choose to do whatever voicing you please. As a result, this method allows for countermelody lines to follow unique pathways separate from the direction of the melody.

Up second is a technique that is very similar to a diatonic passing chord but enforces a few more rules when using it. It’s called diatonic planing. Like the previous method, you can only use diatonic planing when the non-chord tone is a note of the key you’re in. However, this technique focuses more on the voicing shape of the proceeding chord than the specific diatonic chord which is used.

To fully understand what diatonic planing is, it’s best to break the name down into its two components: diatonic and planing. We’ll begin with the latter. Planing is a simple technique where you capture the same voicing shape of the chord you are resolving into. The diatonic component restricts what type of notes can be used within that voicing to those from the given key. Afterward, you can work out which diatonic chord you created from the voicing if you wish, but that detail doesn’t matter as much.

So let’s have a look at how diatonic planing works using a real scenario. In the key of C major, if you had a G7 chord voiced out D, F, G, with B as the top note then any diatonic non-chord tone which led into that voicing would have to use the same shape. For example, an A resolving up into the B, the voicing would be C, E, F, and A on top. Resulting in the passing chord being an Fmaj7.

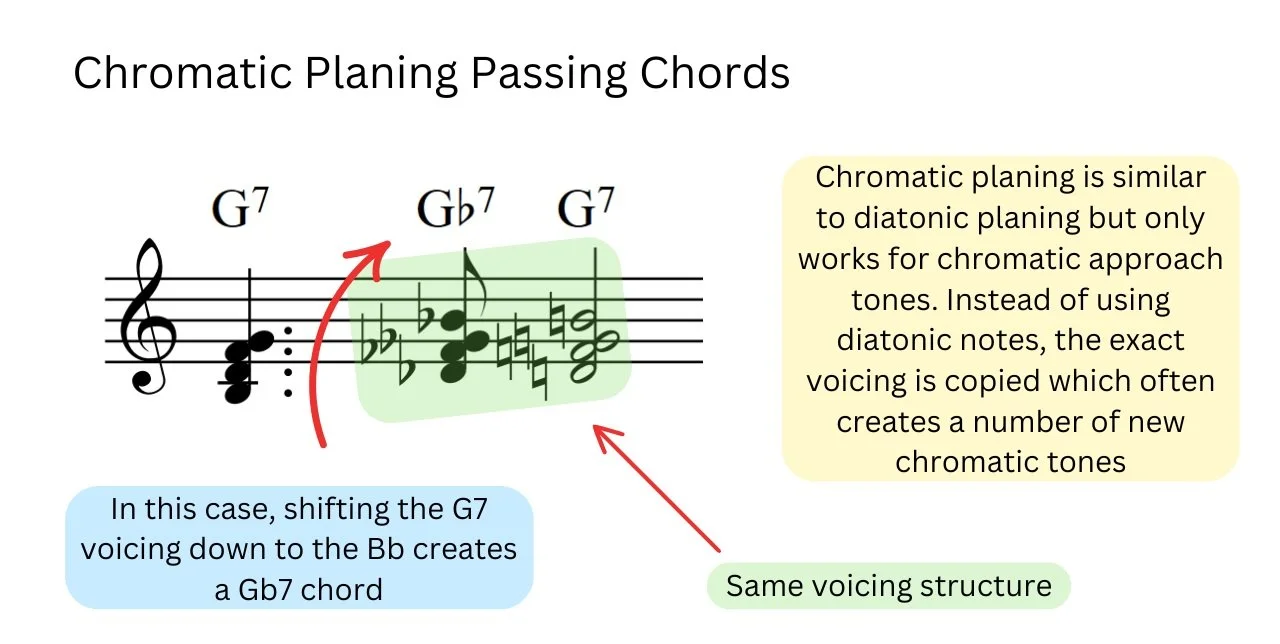

The next technique is quite similar and is called chromatic planing. It operates in the same manner as diatonic planing, however is used primarily for non-chord tones which approach a given chord by semitone/half-step. Instead of creating the planed voicing with diatonic notes, the passing chord must be voiced with exactly the same voicing structure as the proceeding chord. That means, exactly the same interval relations within the voicing. Another way of thinking about this is that chromatic planing is approaching a given voicing but shifting it all down or up a semitone/half-step depending on which direction the note is resolving. The end result is quite satisfying as it introduces a level of dissonance from the chromatic notes to the key but then immediately resolves them.

For example, if we looked at a G7 chord voiced D, F, G, with B as the top note, you could use chromatic planing if the preceding non-chord tone was either a Bb or C. From there you capture the exact same voicing, only a semitone/half-step away. If the passing chord was built from the Bb the voicing would be Db, E, Gb, Bb, and if it was approaching from C it would be Eb, Gb, Ab, and C. The associated chords would be Gb7 and Ab7 respectively.

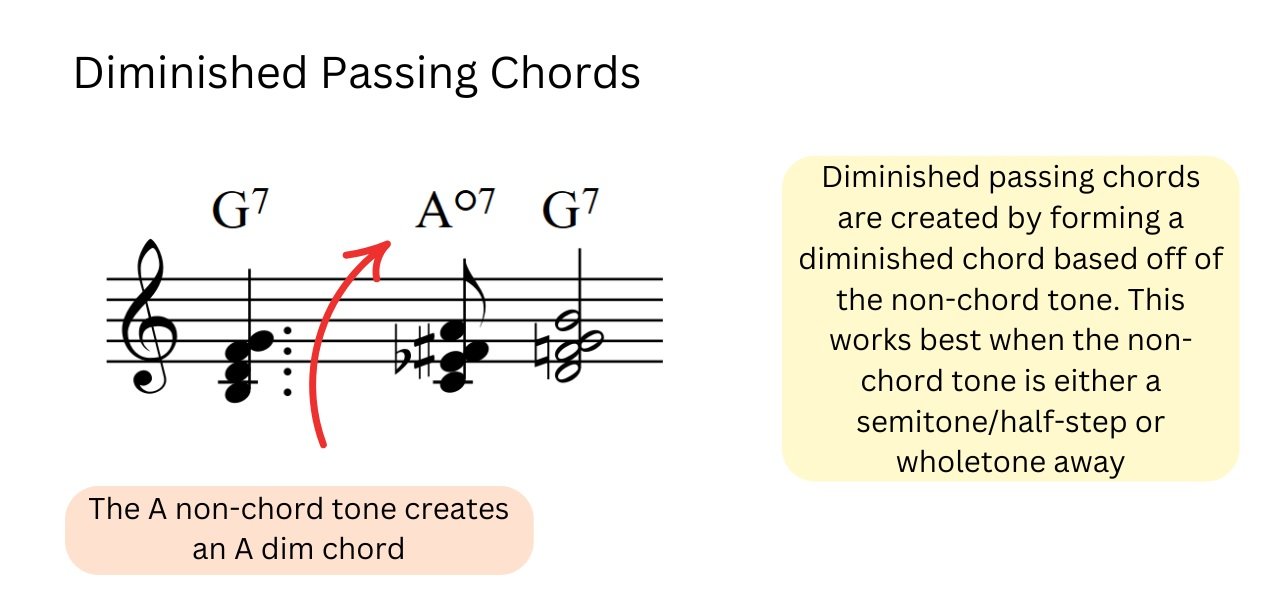

Moving on from planing we have the diminished passing chord. Out of all of the options, this technique is by far the most versatile, mainly because it can be used on both chromatic and diatonic approach tones. It is also one of the simplest to understand as all you have to do is voice out a diminished chord based on the non-chord tone in question. For example, if you had an A as a passing note, then you’d simply voice it with an A diminished chord. The best results come when the approach note is either a semitone/half-step or whole tone away.

Last but definitely not least are dominant passing chords. This may be one of the most popular ways to harmonize non-chord tones in jazz arranging as it can be used in conjunction with other techniques. Fortunately, dominant passing chords operate in exactly the same manner as secondary dominant chords. First you choose the chord that you are approaching and think of it as a temporary I chord in a new key. From there, you work out the V chord in that key and that’s the chord you use to voice the non-chord tone with. In order to use this technique, the approach note must be part of the secondary dominant chord. For example, if you had a G7 voicing, then an approaching non-chord tone could be voiced out as a D7.

To take this technique a step further, you can combine substitution techniques as well as add any number of extensions and alterations to a dominant passing chord. That means you can tritone sub it if you like, as well as interpret it with any number of appropriate scales such as ½ W Diminished to access interesting color tones.

Target Practice

Earlier, I defined what a non-chord tone was but only gave you an introductory definition. That’s because when you start learning these techniques I’ve found it far easier to begin in situations where they will work immediately. Although my definition of a non-chord tone still stands, in the world of jazz arranging we have the freedom to voice any note in a phrase as a passing chord, not just non-chord tones. You can also string multiple passing chords together. As you can imagine, in many cases that will lead to some pretty bad outcomes and can also feel incredibly overwhelming if you haven’t used a passing chord technique before.

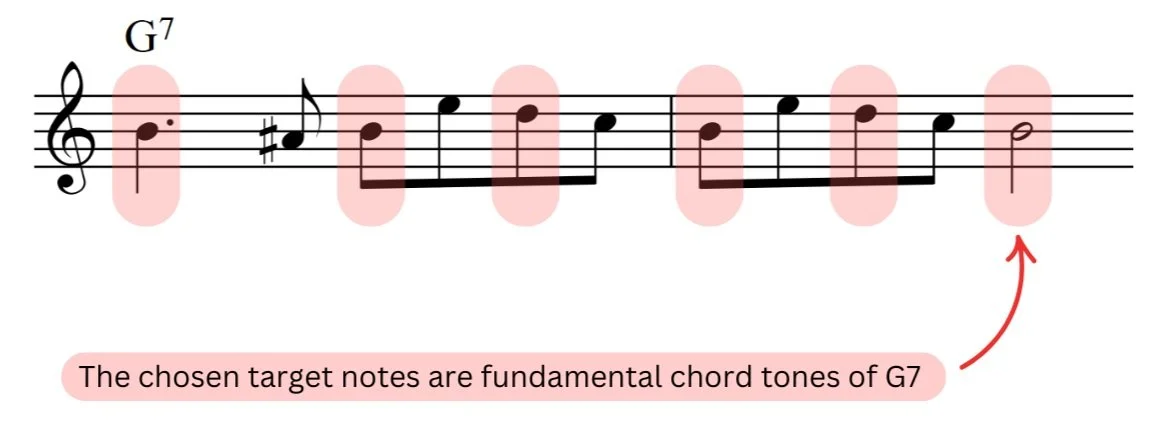

So if we now have the ability to make any note a passing chord, how do we know which ones should, or maybe more importantly, should not be? Well the secret comes down to how we select target notes. A target note is the note a passing chord resolves into. It doesn’t have to be a particularly significant note in a phrase and generally is just a note which is a fundamental chord tone of an accompanying chord.

Once we’ve selected the target notes we can then voice them out. To keep things simple I’ll just stick to triadic voicings for now.

This leaves the remaining notes as passing chords which we can now assign any of the five techniques we’ve just discussed.

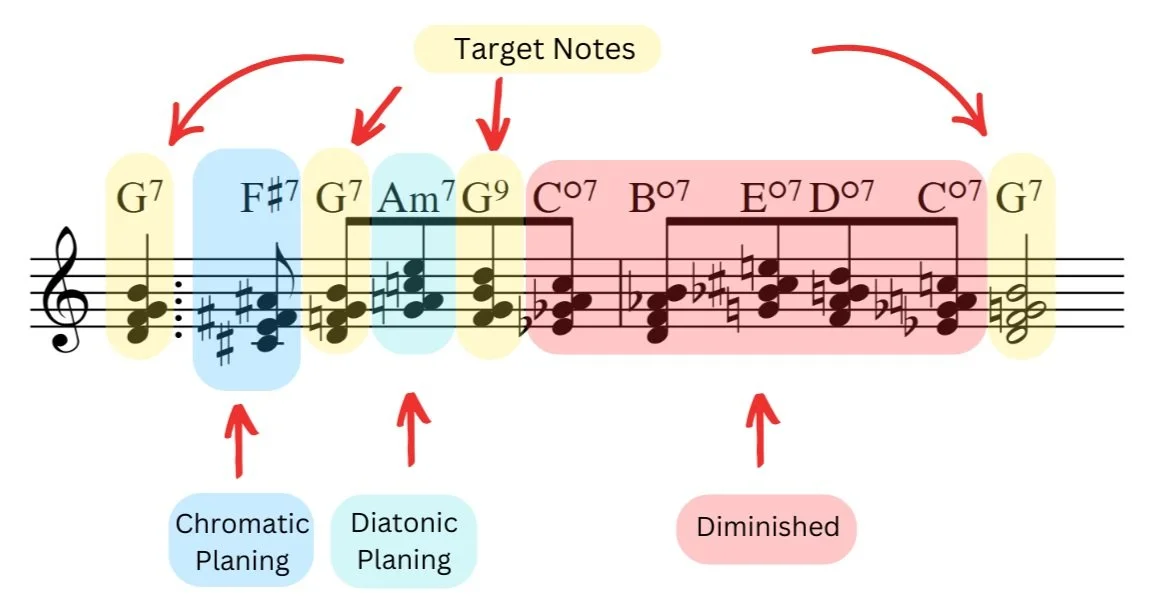

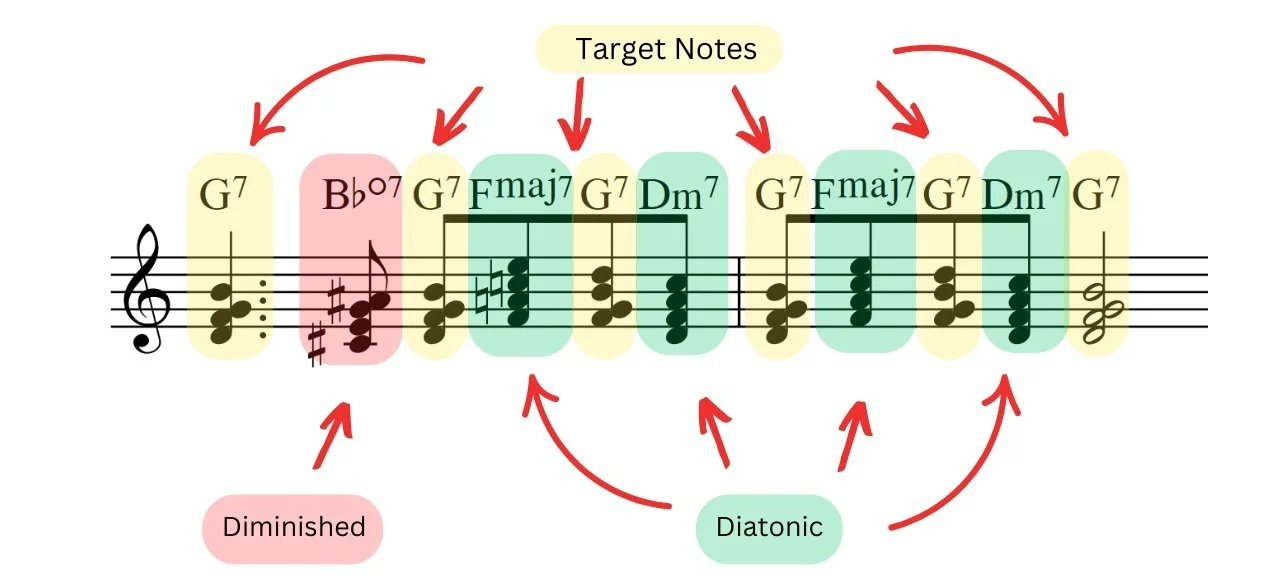

We can drastically change how a phrase is harmonized through which notes we select to be target notes as well as which passing chord technique we use. As a result, that gives us numerous combinations to explore. Using the same melody as above, here’s a few other options where I have shifted the target notes and used different variations in passing chord techniques.

Context plays a big factor in what combinations feel “correct” and “incorrect.” For example, in some styles certain passing chord techniques are the only ones used and there is far less freedom with target note selection. Whereas in others you can run rampant and go anywhere you want. As you practice using them, take note of what combinations you enjoy using and what other arrangers have used in certain contexts. Here’s an example of how Duke Ellington incorporated a number of different techniques into a trumpet line in his composition “Sugarhill Penthouse.”

Sugarhill Penthouse

Duke Ellington

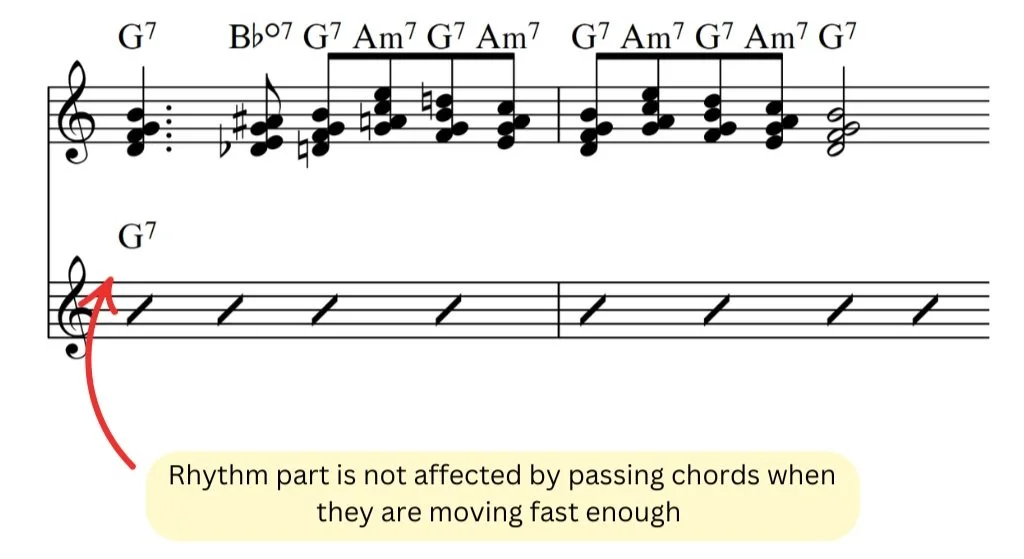

Misleading Chord Symbols

Now that we’ve established what a passing chord is and where to use them, there’s one last area to address: chord symbols. When you voice out a passing chord, oftentimes it can clash with the preexisting chord progression. This is usually not an issue if the passing chord is for a quick moving line or on a quaver/eighth note. That’s because when a passing chord moves fast enough, the introduced dissonance is resolved before it really impacts any of the accompanying harmony instruments. What this looks like in reality, is that the rhythm section will see exactly the same chord changes as usual regardless of any passing chords going on.

However, in some instances a passing chord may land on a note of longer duration and those dissonant tones are heard more prominently. When this happens we have to add a new chord symbol to the progression so that any accompanying parts won’t clash with the passing chord. This is more typical in slower tempo pieces and is one reason why you see far more chord symbols in ballads.

Li’l Darlin’

Neal Hefti

There is no specific tempo marking or note duration where passing chord symbols should start to be added to a chord progression. My suggestion is to use your best judgement and make edits based on any issues you hear when the arrangement is played live. Over time you’ll develop a sense for when it is necessary and when it isn’t.

Longer Formats

Up until now we have been looking at using passing chords within a melodic phrase, acting as a fast moving bit of tension within a larger accompanying chord symbol. However, we can also look at passing chords on a larger scale in the context of a whole progression. Not only are passing chords useful for harmonizing non-chord tones, they also can help bridge the gap between two chords within a progression. In these cases we can still turn to our five passing chord techniques, but there are also a few more options available too.

When approaching a passing chord in this sense, we can start looking at the normal chords we have at our disposal and whether we can change the functionality they imply. What I mean by this is that just because a root position I chord is considered a T function, perhaps there may be a way of changing how we perceive the chord. In my experience, the best way to do this is through inversion.

As mentioned in this resource, when we invert a chord we hear the inner intervals in a different light. When this happens, it is possible to change the functionality of a given chord. For example, in the key of C major if we had a I chord in root position it would feel very stable like home. However, if we put that same chord in second inversion to create C/G we start hearing it as some sort of Gsus sound, associating it more with the qualities of a V chord than a I.

It doesn’t matter too much whether you hear it more as a T or as a D function as context definitely can push it into one camp or the other. The main takeaway is that the functionality was affected to some degree and the strong feeling of T was weakened. Not every diatonic chord will change so drastically as the I chord in second inversion, but every chord's original function does diminish by putting it in an inversion. This can be useful in a progression as we can use these less functional variations to connect other chords together. For example, in the key of C major if we had a Dm7 going to an Fmaj, we could connect them with a C/E or a C/G chord and it wouldn’t feel like a cadential point. Instead, the inverted chord would feel like a passing chord between them.

Similarly to how we defined non-chord tones earlier, when looking at passing chords as a tool to connect chords in a progression, the duration and rhythmic placement also impact whether we perceive the chord as a passing chord or not. For example, using the prior progression of Dm7-C/E-Fmaj, if we put the C/E on a prominent beat and it lasted longer than either of the surrounding chords, we would not perceive it as a passing chord and start hearing it more as some kind of T chord.

Other than inversions there is one other way we can affect functionality and that is through which extensions we use. The more notes we add to a chord, the more we define its overall feeling, and sometimes that leads to a complete change in function. One such example is the vi chord in a major key. In a triad, a vi chord has a strong T functionality. However, as soon as you add a m7 to it, it weakens. Furthermore, if you keep adding extensions such as the 9th and 11th, it continues to weaken and starts being perceived more as a PD. That’s because having the m7 makes it feel closer to a dorian sound which we associate with the PD function. If you were wanting to add extensions but maintain a T functionality, the 7th would need to become a M7 like it is in melodic or harmonic minor, creating a minmaj7 quality.

By weakening the functionality of a chord through extensions and alterations, we find even more options for passing chords. For example, in the key C major, an Am7 (or Am11 if using color) chord could be used in a passing fashion far more easily than a root position Am as the m7 weakens the functionality.

So to recap, the key to using chords outside of the five passing chord techniques we introduced earlier is to weaken the functionality. That way when you land on the chord it doesn’t feel as strongly like the original function and potentially create an unwanted cadence point. It should also be mentioned that if you were thinking of weakening functionality by combining inversions with extensions/alterations that the results may not work that well. This is because at a certain point chords with lots of color notes in inversion start feeling like a completely different chord altogether. For example, C13#11/E could be perceived as some kind of Em7b5 chord, or G7#5#9/Eb could be heard as Eb9b13. Depending on the specific situation, this could be problematic.

When Fancy Techniques Aren’t Needed

Sometimes when you come across a non-chord tone the best option is to not use any passing chord technique at all. Instead you can look at the chords surrounding the given bar and simply find the one that best fits the non-chord tone. For example, if you had a non-chord tone of B in a bar of Dm7, if the following chord was a G7, you could harmonize the B with that chord. It’s not the fanciest approach, but it works surprisingly well and is worthy of mention.

The Takeaway

For me, passing chords are one of the most interesting parts of jazz arranging. With so many options, you can completely change the sound of a passage through how you select target notes and which passing chord technique you use. Getting the hang of them takes a little while and if your experience is anything like mine, you may create a few abominations before things start to make sense.

So where does that leave us? Well if you’ve come through the resources to this point you’re in a great position to start learning how to orchestrate all of the awesome harmony techniques we’ve discussed. That means the best place to go from here is knowing more about the instruments we plan to write for by understanding the range, register and transposition of each one.