The Key To Writing

For Any Instrument

Somewhere along everyone’s arranging journey they stumble upon a section of a book, or a class, which unpacks the details of each instrument. If you’re like me, you may not have given too much attention to this particular subject because you wanted to get to the “good stuff,” the fancy voicings and crazy substitution techniques. However, as I get older I realize that understanding the qualities of each instrument you write for may just in fact be the most important part of the writing process. If you don’t know how an instrument is going to sound when you write for it, then anything could happen once you get to the bandstand.

Unlike the other resources, I’ve chosen to break this particular subject into a number of mini sections which build on each other. It’s common for resources to introduce areas like transposition, range, and register as one collective, but I feel that takes away from the importance of each topic. Up first is transposition.

Do I Really Need To Know Transposition?

These days we are lucky to live in a time where notation programs do the hard work of transposition for us. We simply plug in our notes and press a button and everything shifts to the necessary key for the instruments we write for. There’s nothing wrong with this at all and like a calculator, it speeds up the entire process. The issue comes when we start having to interact with the transposing instruments out in the wild, where we most likely can’t rely on the safety of our technology.

Even though I began my arranging journey with the aid of Sibelius, one of the first exercises I was given was to transpose the assigned melodies for a number of different instruments by hand. Initially I was confused. Why would this be of any value to me as a writer now that I can rely on technology to do the job for me? Although I learnt how to correctly transpose for the given instruments, albeit rather slowly, the task didn’t seem relevant. In fact, it was nearly two years until I realized exactly why transposition is a critical skill for any arranger.

It was my final semester of university, which meant recital time. As an arranging major, I had to write a number of big band arrangements and then perform them. Although I had been writing for a couple of years at this point, this was the first time I was going to be conducting a big band through my charts. Other than being scared out of my mind, the entire experience highlighted a lot of key areas I needed to improve. One being my ability to transpose.

You see, when we got to the first rehearsal for the recital we read the sheet music down. In my mind that was all I needed to do, then came the bombardment of questions that the players had about the chart. Things like “is my note in bar 42 correct.” Even though I had the score in front of me, it took me forever to find the note in question, transpose it to concert, and then check it with the chord symbols and voicings I’d written. Specifically the transposition part. I was lucky that the band was mainly made up of my friends so they were happy to be patient with me, but I realized rather quickly that I wouldn’t be afforded the same luxury in most professional situations.

The main point I’m trying to emphasize is that digital notation is great for the actual writing component of arranging, but if you are ever going to be standing in front of a band, then it is essential to understand the transposition of each instrument you are conducting. At the end of the day, it is definitely a skill worth having even if it only gets used minimally.

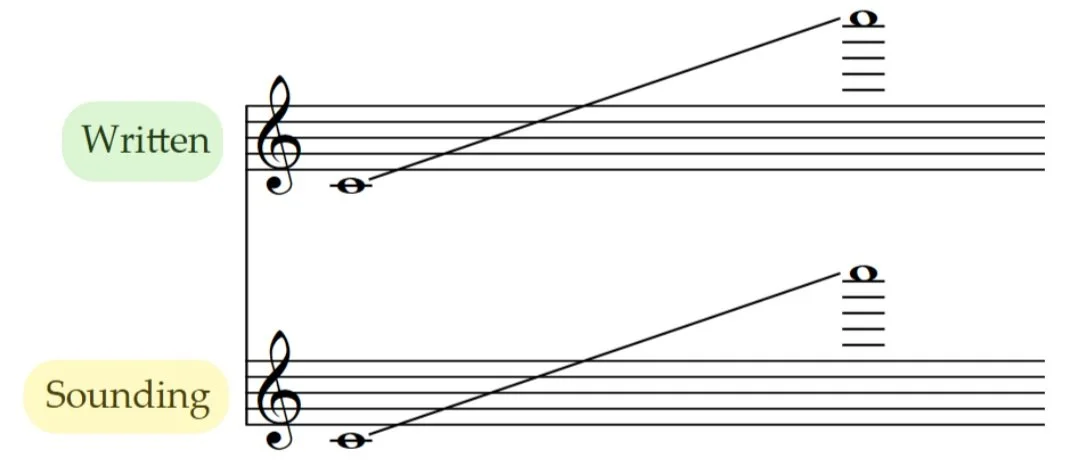

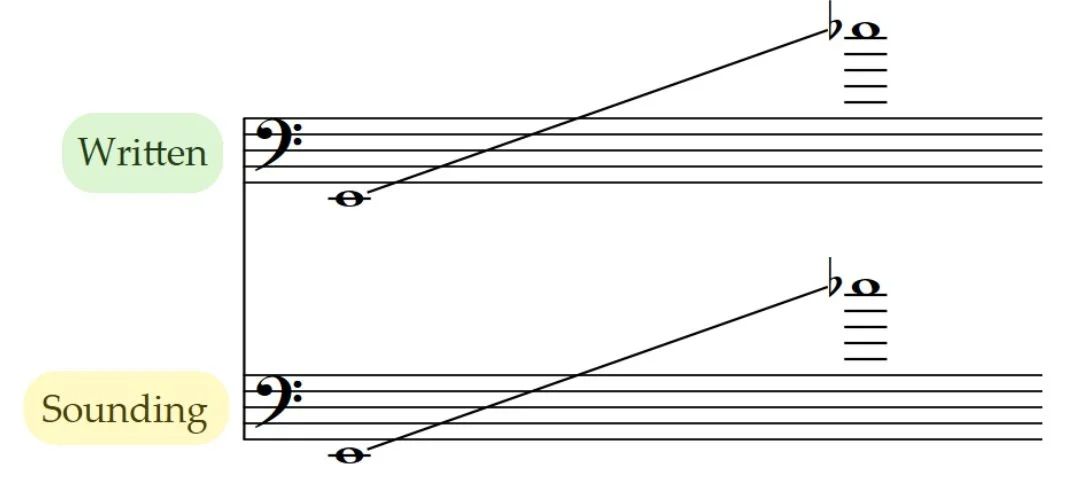

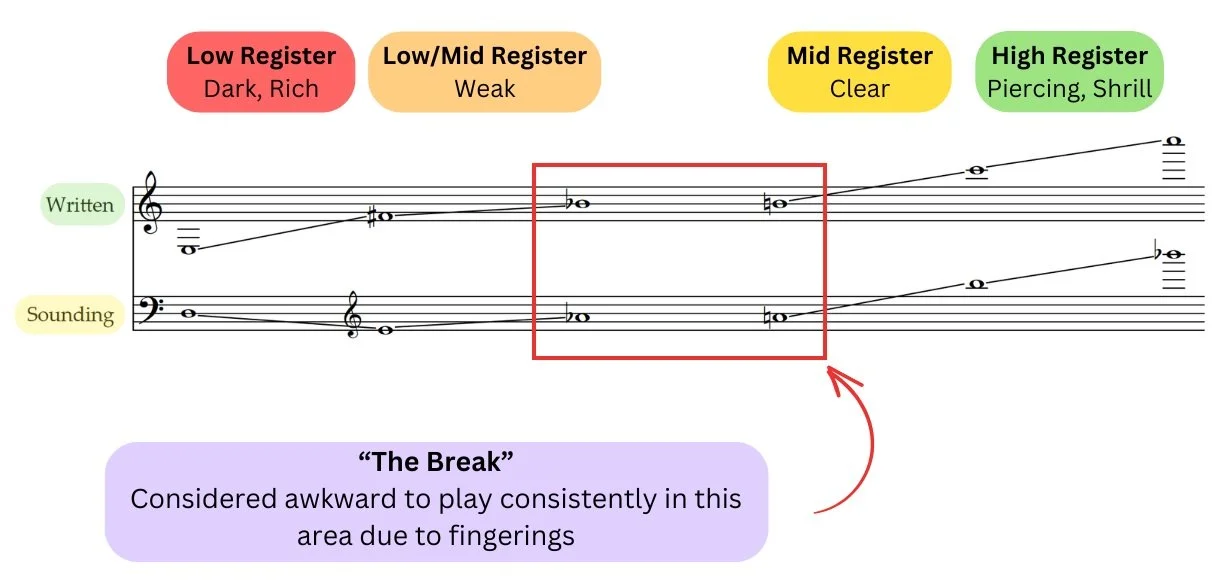

So what is transposition and how does it work? Well it was created as a means to position every instrument so that a majority of their notes land within a given staff. Ironically, it is a broken system that not all instruments follow, creating frustration among everyone and some exceptional cases where certain instruments like the trombone mainly live in the ledger lines above the bass clef staff. It works by shifting the music of certain instruments from concert pitch to a new key which better suits that instrument's range. Although the notation has been shifted, audibly it is still heard in the original key, creating the need for terminology which defines whether the notation is transposed or in concert pitch. For the sake of this resource that will be sounding for the original concert key, and written for the transposed instrument key.

As there are a large variety of transposing instruments, to keep it simple I’ve restricted this resource to cover only the instruments commonly found in a jazz/big band setting. Namely, trumpet, trombone, the four main saxes, flute, clarinet, piano, guitar, and bass. To find information on the instruments that fall outside of this group, I would suggest looking at any introductory classical orchestration book.

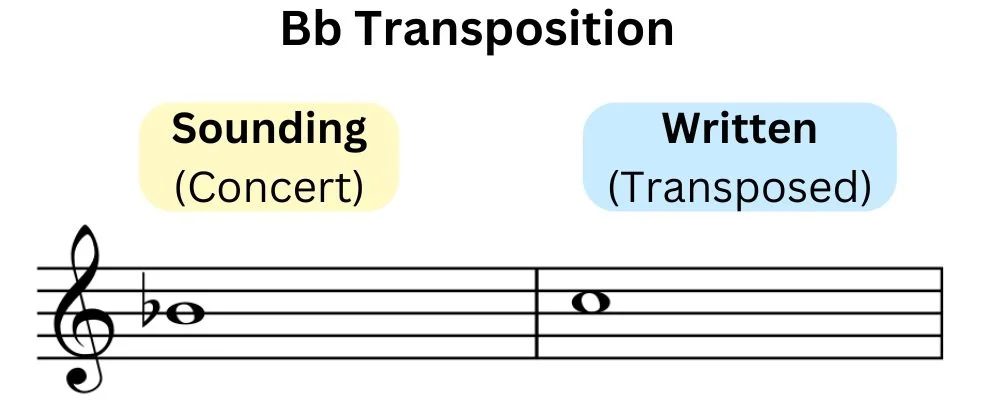

Within the common jazz instruments there exist three different transposition categories that you should be aware of: C (concert) instruments, Bb Instruments, and Eb instruments. The specific transposition name for each category gives us an indication of how the instrument relates to concert pitch. For instance, when an instrument is a Bb transposing instrument, it means that a sounding concert Bb is written as a C for that instrument. The same concept applies to Eb instruments where a sounding concert Eb is written as a C.

C (concert) Instruments

Flute

Trombone

Piano

Guitar

Bass

Bb Instruments

Trumpet

Clarinet

Soprano Sax

Tenor Sax

Eb Instruments

Alto Sax

Bari Sax

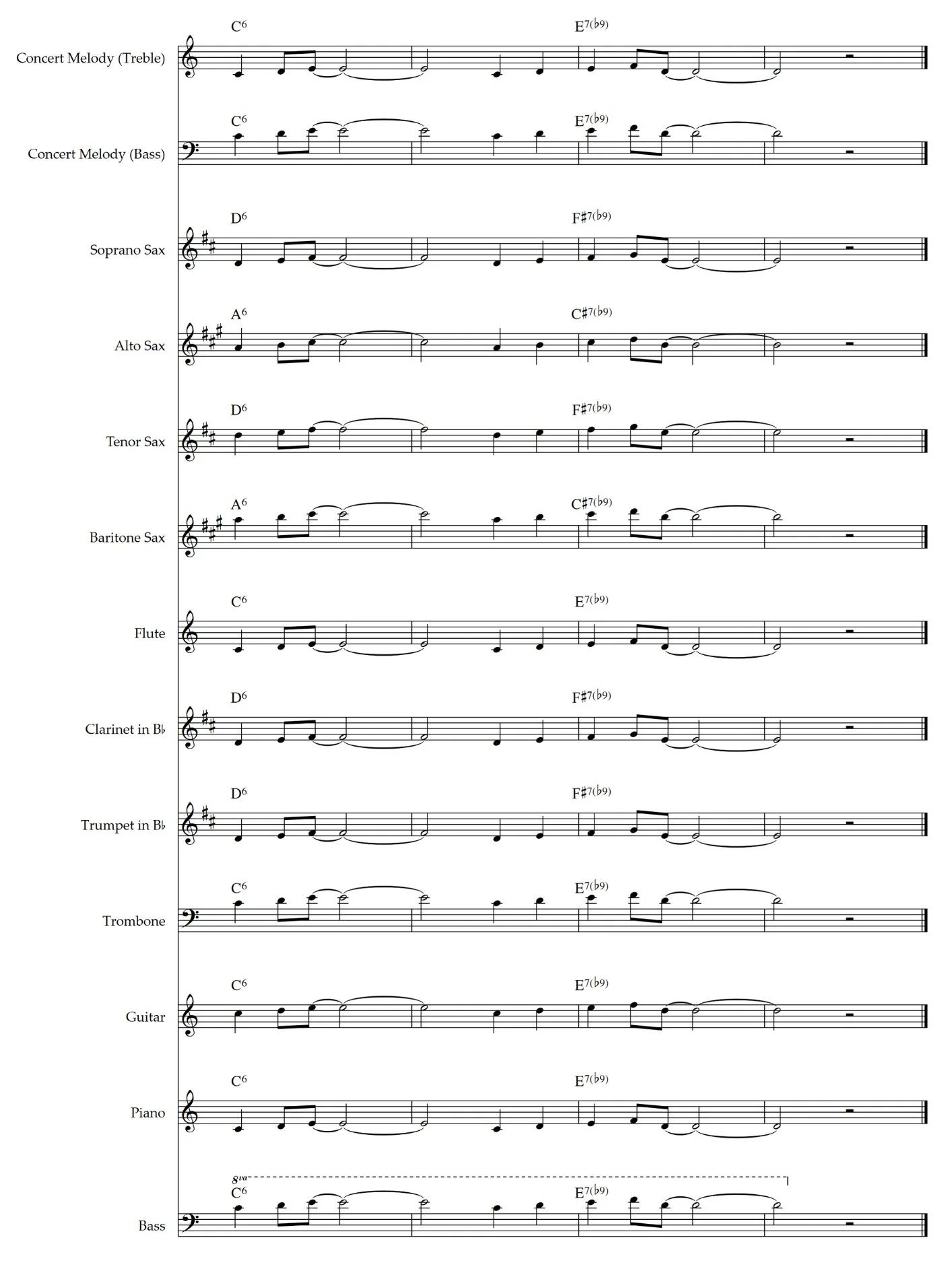

To add a little bit more difficulty into the mix, just because we know how each instrument transposes, doesn’t mean we know in which octave a given note is written. For example, an alto sax is written a M6 above the sounding note, whereas for a bari sax to play the same note it would need to be written an octave higher. Below you’ll find specific breakdowns on each instrument and how they transpose.

Soprano Sax (Bb)

Transposition - Bb (up a M2)

Clef - Treble

Alto Sax (Eb)

Transposition - Eb (up a M6)

Clef - Treble

Tenor Sax (Bb)

Transposition - Bb (up a M9)

Clef - Treble

Bari Sax (Eb)

Transposition - Eb (up a M13)

Clef - Treble

Flute (C)

Transposition - Concert

Clef - Treble

Clarinet (Bb)

Transposition - Bb (up a M2)

Clef - Treble

Trumpet (Bb)

Transposition - Bb (up a M2)

Clef - Treble

Trombone (Bb)

Transposition - Concert

Clef - Bass

Guitar (C)

Transposition - Concert (up a P8)

Clef - Treble

Piano (C)

Transposition - Concert

Clef - Treble & Bass

Bass (C)

Transposition - Concert (up a P8)

Clef - Bass

Just to push the point of how these instruments transpose a little further. Here is an example of how the same melody would be transposed for each of the given instruments. I have not changed the octave to accommodate for lower or higher pitched instruments so that a true comparison can be made.

Playable Parts

It seems to be quite common that writers downplay range in the arranging process. For some reason when most people compose they seem to come up with a line first before thinking about an instrument that will play it. Or, if they want it to be played by a specific instrument, they often don’t alter their writing process to accommodate the limitations and abilities of that instrument. The most obvious example is when it comes to lead trumpet. Don’t worry, I’m not going to sit on a high horse and judge others who do this, I’ve been through the crucible with my own trumpet writing and have the scars to prove it.

My first interaction with lead trumpet parts was a subconscious one during high school. I was in my mid-to-late teens and was being introduced to classic big band recordings as well as a bunch of artists such as Tower of Power and Earth, Wind & Fire. Without knowing it, I was building an association with horn writing that focused on high trumpet notes.

Jumping ahead a few years to when I began writing for trumpet, I thought it was perfectly acceptable to expect all trumpet players to be Wayne Bergeron (LA studio musician). If you have any experience with trumpet players, you know that this is definitely not the case. Unfortunately, the university I went to had a dedicated lead trumpet professor who attracted dozens of killer players with exceptional range. On one hand I was incredibly lucky to play alongside these talented trumpet players who could play anything I wrote, but on the other hand it reinforced the belief that everyone could play high notes.

Once I moved back to Australia, I was given a reality check in two ways. There was a smaller number of lead trumpet players in my local scene that could play the music I was writing, and when I started writing arrangements for school bands the trumpet lines were way too ambitious. In other words, they were unplayable.

After a few too many gigs and rehearsals not realizing my error, or perhaps being too stubborn to address it, it finally dawned on me that I was not considering the range of the players I was using. I changed my expectations and began approaching the trumpet parts differently. And you know what, the music benefited considerably. Even though I wasn’t getting the ear splitting high notes I originally wanted, the ensemble as a whole sounded much better.

Range issues are also not limited to just lead trumpet writing. During my time on cruise ships I witnessed a number of less than ideal arrangements hit the band stand. All too often there were charts where instrumental parts were so low they were unplayable. To my luck that helped me get a start writing for cruise ship clients but it was an issue that should never have made it to the band stand in the first place. My guess is that the original arranger was composing through a DAW which allowed certain samples to play lower than what was possible. The performer signed off on the mockup generated from the DAW, and then unfortunately the musicians were left with the issue of how to fix it during the performance.

So what are the ranges of the common jazz instruments? Typically they cover a two-and-a-half octave spread and are located in a number of different locations. To help identify instruments which share similar ranges, we typically use four classifications: Soprano, Alto, Tenor, Bass. There are more than just those four but for now they will get the job done. There are limitations to this method, namely that every instrument does have a unique range and that just because they may share a classification with another instrument, doesn’t mean they will have an identical range. For example, a soprano sax and a trumpet are both classified as soprano instruments, yet they don’t share the same lowest or highest possible note.

Soprano Sax (Bb)

Classification - Soprano

Alto Sax (Eb)

Classification - Alto

Tenor Sax (Bb)

Classification - Tenor

Bari Sax (Eb)

Classification - Baritone (between bass and tenor)

*Most bari saxes have a low A key which extends the range by a semitone/half-step from written Bb to A

Flute (C)

Classification - Soprano

Clarinet (Bb)

Classification - Soprano

Trumpet (Bb)

Classification - Soprano

*The trumpet can go even higher than the range marked but it is dependent on the individual player

Trombone (C)

Classification - Tenor

*Like the trumpet, the trombone can go even higher than the range marked but it is dependent on the individual player

Guitar (C)

Classification - Unclassified

*The range of the guitar is dependent on the instrument and can be larger or smaller depending on the number of strings and frets

Piano (C)

Classification - Unclassified

*The range may be reduced or extended depending on the number of keys available

Bass (C)

Classification - Bass

*The range of the bass is dependent on the instrument and can be larger or smaller depending on the number of strings and frets (or size of the fingerboard for upright bass)

Often when arranging gets taught there is a preference for writers to compose at the piano. This comes from a time where it was the only accessible feedback device you could get other than bringing in a chart to a band. However, the tradition has lived on even though we now have digital notation software, samples, and DAWs that can provide a more accurate representation of the music we write. There is nothing wrong about writing at the piano, in fact it will more than likely help you get closer to the music, but there are limitations that you should be aware of.

When playing piano, you don’t hear the ranges of other instruments, you simply just hear it all as it relates to the keys you play. As a result, many pianists who write often have issues with writing within the range of other instruments when they start out, because they are actually just composing melodies that sound good on the piano. To combat this, one recommendation I got from my arranging professor Rich DeRosa, was to mark the keyboard with colored tape to indicate the lowest and highest points for each instrument. That way when you are writing you have a quick reference guide to what notes are playable for a given instrument.

One Topic To Rule Them All

Out of the topics discussed on this page, one reigns supreme as it impacts the music far more than any other. It affects texture, timbre, projection, balance, dynamics, and I’m sure a half dozen or so other areas of an arrangement. I was introduced to it back in 2014, however it took me six years to really understand the power it has when arranging. I’m talking about instrument registers.

Similar to transposition and range, I was introduced to register in my first arranging class. There are a few takeaways I still remember which will find a way into other resources but for what it’s worth, as soon as I got into the real world register wasn’t something I thought about. That is until I had accumulated enough experience and critique to realize I had to take it seriously.

Coming out of university I was itching to write charts for real clients. Over a couple of years I had amassed numerous techniques that I wanted to unleash upon the real world, and as luck would have it, I got to. Up until 2020, I would arrange a lot, mainly recycling the voicing techniques I had learnt, giving no care to the specific sound of the instruments I was writing for. However, this approach landed a few critiques over the years and it wasn’t until the beginning of 2020 when I was faced with a comment which changed my entire perspective.

I had just written a 45 minute suite to feature a local trumpet player Mat Jodrell. At that time of my life I was putting in serious hours on a number of projects so I ended up writing the entire suite in the week leading up to the performance. It wasn’t my finest work but still held together well enough. One of the movements was a light modal bossa with Mat on flugel. After the show I asked him what he thought and he mentioned that the entire melody was quite high in the flugels register and it would probably be better suited lower on the instrument. I politely listened but didn’t act on the information at all. That was until two months later we were hit with the first COVID lockdown.

During the multi-month stint at home, I turned to teaching online like many other musicians, specifically focusing on arranging topics. Like every other arranging course, I started with teaching the basics on range and register even though I didn’t actually think about it too much in my own writing process. However somewhere along the line something clicked, whether it was Mat’s comment, looking back over my notes about register, or a mixture of other critiques I had received, I realized that register may be one of the most important aspects to writing.

As I had now reached the point where I had a number of years of experience writing charts and hearing them performed by real musicians, my mind connected the dots and it made sense why register was so impactful. Every instrument has a number of different registers each of which sound and feel different. Some registers the instrument may cut through an ensemble easier, some they may sound shrill, some they may sound boomy, some they may sound muddy. There are endless individual texture differences that come together to create an arrangement.

By focusing purely on voicings, I realized that I completely ignored the texture and timbre that the instruments would sound like. Of course I was still aware of some things like lead trumpet cutting through in the high register, but it never played a prominent role in my writing. With this almost overnight epiphany, I started editing and redoing a lot of my charts to see if I could get better results by prioritizing register. Surprisingly, it did. However, that’s where I’m going to cut this story off because this is not a section on voicings. You’ll have to wait for another resource to see how register impacted my voicings.

So with all that in mind, the best thing about register is it allows us to understand how each instrument will sound no matter where we place a note. For example, a trumpet note in the high register will sound bright and cut through an ensemble, whereas if you placed the note in the middle register it would have a more rounded tone and not have as much of a dynamic impact. Whether you’re new to this topic or a seasoned veteran, I can not recommend taking the time to understand instrument register. I consider the single most impactful aspect to my arranging journey the prioritization of register.

Soprano Sax (Bb)

Alto Sax (Eb)

Tenor Sax (Bb)

Bari Sax (Eb)

Flute (C)

Clarinet (Bb)

Trumpet (Bb)

Trombone (C)

Guitar (C)

Piano (C)

Bass (C)

Slotting A Melody

By understanding register it paves the way for us to write melodies on any instrument and feel confident in how it will sound. There’s nothing worse than writing a beautiful melody only for it to not feel right due to the timbre of an instrument. When you’re just starting out, the best practice is to slot a melody in the middle register where possible. That’s because the middle register is typically the easiest to play in and provides the most neutral tone.

For example, if we take the melody of Autumn Leaves in the key of concert Bb Major/G Minor and assign it to the alto sax, a lot of the longer notes land just above the middle register. To play it safe, it would be ideal to lower the whole melody by at least a M3 or P4 to locate the majority of the notes in the middle register. That would give us the key of concert F Major/D Minor.

The practice of shifting keys to accommodate instrument registers is quite common when it comes to vocals but for one reason or another, it doesn’t seem to be done as much for wind instruments anymore. One possible issue with shifting melodies based on register is that you may have a lot of modulations between sections. This is when it is essential to understand how to change keys smoothly so that it doesn’t take away from the music. Here’s a resource I’ve written on the topic.

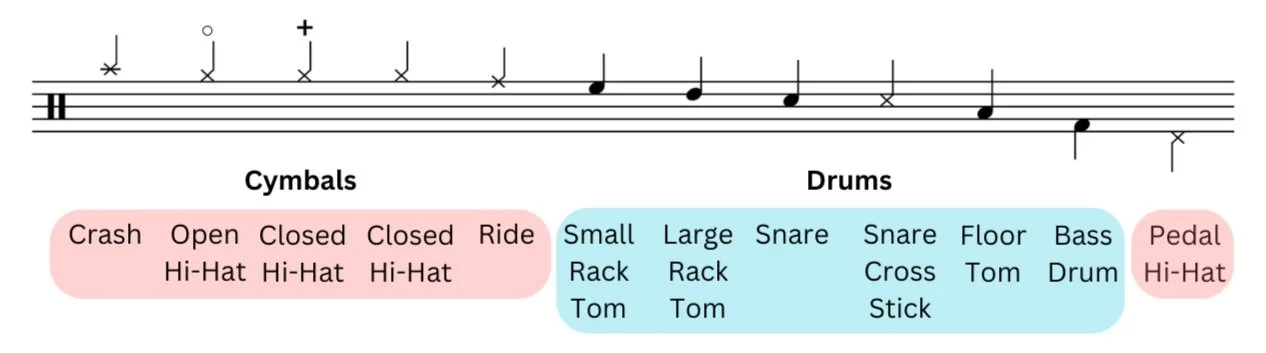

Give The Drummer Some

With all of that talk about register I think it’s time to move to a different topic for a moment and look at the confusing world of drum notation. Unfortunately we live in a world where drum notation is inconsistent and many drummers disagree with how their music should be laid out. This can make it a tricky landscape to navigate and one which took me years to learn.

My first interaction with drum notation came in my first semester of university where I was given the task to transcribe every element of a given pop song. I felt comfortable with the chords and melody but had no clue what to do when it came to the drums. I briefly messed around with the drum sounds on Sibelius to no luck and eventually turned to one of my drummer colleagues for help. He ended up writing out the entire part for me (as well as everyone of my non-drum playing friends) which got me a pass for the assignment. At the time I was committed to becoming a great jazz bassist so quickly wiped anything he told me about drum notation from my mind.

A few years later once I had changed my emphasis to jazz arranging, I was once again given the task to write a drum part. As I had not remembered anything from that first semester assignment, I turned to another drummer in the program to see what they liked and disliked. He mentioned that he would often prefer to see a notated horn part as it would usually give more information than a standard drum part. Although useful, this nugget sent me down a direction which wasn’t the most helpful as I took his words literally and just gave drummers lead trumpet parts for a few years.

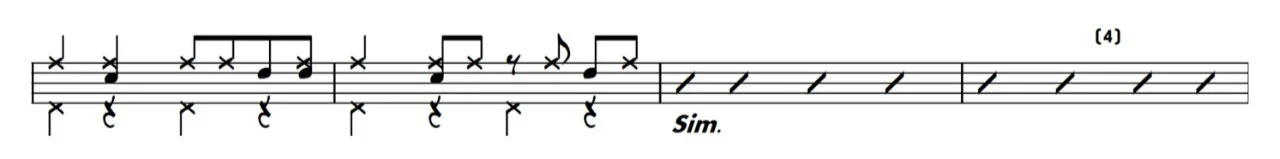

Another couple years passed and I was now playing on a cruise ship. The opportunity came up to write for the band so I decided to do an adaptation of the Brecker tune Some Skunk Funk. Approaching the drums like I had been in college, I gave the drummer a horn part. However, this time it didn’t turn out so well. The drummer got quite annoyed at me and said something about the part not being helpful at all. Once again I had to learn how to write for drums so I approached the task by fully transcribing the Peter Erskine part from the record. The next day I brought the new part into rehearsal only to be shouted off the bandstand again because of how much ink was on the page. I had obviously gone a bit too far by notating everything that Erskine had played which made it impractical for our situation. For the final time, I went back to the drawing board and redid the part one more time, simplifying it to have a template of the groove followed by slashes and any important hits being notated. This time the house drummer was much happier and I had finally found a winning formula.

Since then I’ve adapted my drum notation techniques to include as much relevant information as possible while still being simple. It’s always a fine balance but so far the results have generally been well received. The main point to remember is that there are many different correct views on what a good drum part should look like. When you write for the instrument, try to be as knowledgeable as possible and have a good idea of what you are writing. That way you can accurately communicate it to the drummer and work out the best way for it to be notated. Here is the system I use.

Typically when creating a groove I group stems upward for drums and cymbals played by sticks, and downward for those played by the feet. I also allocate different notes for each cymbal, however it is common just to use the same note for all cymbals and to use text to dictate which cymbal needs to be used. When I want the drummer to keep playing time I use slashes with any hits alongside the groove being notated above the staff with cue noteheads. Otherwise if I want the drummer to stop playing time and only play the hits, I’ll use slashes with stems within the staff. Finally, when I want a drummer to fill I will simply write fill above the relevant space.

Other Textures

Alongside register, there are other ways that we can change the texture of instruments by using various equipment or techniques. Every instrument has its own bag of tricks that we can access to create unique musical moments. Whether it be a mute, a bow, or a certain embellishment, arrangers have made use of them all over the last century. Here are some of the most common:

Mutes

Brass instruments have access to a number of different mutes which alter how the sound exits an instrument. Depending on the shape, how much air is allowed to escape, and the material the mute is made of, the overall sound of the instrument can vary drastically. As mutes are placed in the bell of an instrument, they all reduce projection. To use a mute in your writing you must state which type of mute above the passage you want it to be played. When you want it to be removed you write open. Bear in mind that it does take a moment to place a mute into the bell and remove it so changes can’t be made too sudden.

Straight Mute

Straight mutes are generally cone shaped and made out of aluminum which results in a more metallic or nasal sound. Some have described the sound as bright and potentially piercing.

Cup Mute

Similar to the straight mute but typically made out of a fibrous material and a larger cup shape at the end of the mute, the cup mute is far less bright/nasal than the straight mute and is generally quieter.

Harmon Mute

Unlike the previous two examples, the harmon mute is made out of two parts allowing for more flexibility in its use. The design of the aluminum body forces all air to travel through the mute resulting in a more metallic, buzzy, shallow sound than the straight mute. With the stem the sound is similar to old time cartoons and early jazz where musicians would refer to it as the wah-wah mute. When the stem is taken out the mute is most famously known for the sound of Miles Davis, with a cutting metallic buzz.

Bucket Mute

Buckets come in two variations, one which clips to the outside of the bell and another which is inserted into the bell. Both achieve the same effect of dampening the sound and are typically made out of a fibrous material which gives a mellow tone.

Plunger

Unlike all of the other mutes, the plunger can be used dynamically to create various sound effects. By changing the amount of air that escapes the bell, brass players can create a tight sound which replicates a straight mute, a ½ open sound which dampens the overall tone, and a wah-wah sound where the rapidly open and close the plunger. It is very common to be used with different vowel mouth shapes and other techniques like flutter tongue or growling. Typically an “o” is marked above notes when you want the plunger to be open and a “+” is for closed.

Common Equipment

Flugelhorn

Most trumpet players these days also own a flugelhorn, another Bb instrument which shares many similarities to the trumpet however with some key differences. The flugel has a conical bore which helps create a much warmer sound in the middle to lower register of the instrument. It also thins out much quicker as it goes into the upper register compared to the trumpet.

Pedals

Ever since amplification was created, people have created new ways to alter the electronic signal between an instrument and a speaker. Most commonly this is done through the use of pedals and is most popular with guitarists. However, in recent years it is becoming more used with bass, keyboards, and wind instruments. Here are a few of the most popular options:

Bow

As a member of the string family, upright bass has access to a bow which creates a lovely rich sustained tone which doesn’t decay like a plucked string. The correct terminology for when you want a note bowed is “arco” and plucked “pizzicato.

Chorus

A chorus pedal adds a shimmering quality as well as thickens the original sound.

Wah Wah

Similar to what was discussed with the plunger, the wah-wah is a dynamic pedal which shifts the tone of the instrument higher or lower alongside passing the sound through a filter to make it sound like the word “wah.”

Reverb

A reverb pedal emulates the reverberation of music in a larger space, helping to make the tone of an instrument feel more “wet.”

Tremolo

A tremolo pedal rapidly fluctuates the volume of an instrument to create a pulsating sound.

Distortion/Overdrive

A distortion pedal adds a level of grit to the original signal by manipulating the gain.

Delay

A delay records a fragment of the signal and replays it back multiple times.

Techniques

Alongside specific equipment, there are many different techniques that writers can use to add embellishments and personality to the music. These usually come in the form of pitch bending in some capacity and help add a considerable amount of attitude to an arrangement. Here are a few of the most common:

Doit

A doit is a rise in pitch after a note. It is most commonly played by bending the pitch of the note upward and like the scoop, may be exaggerated in various jazz styles.

Scoop

A scoop is an approach into a note from below. It typically features a pitch bend where the duration of the bend can sometimes be exaggerated such as in the Basie style.

Plop

A plop is an approach into a note from above. It can either be played with a pitch bend from above or by approaching the note through the overtone series.

Fall (short)

A short fall is a lowering in pitch after a note. It is most commonly played by bending the pitch of the note downward and is usually quite immediate and is not exaggerated.

Fall (long)

A long fall is a lowering in pitch after a note usually over a period of a bar or longer. It is commonly played by falling through the overtone series over a range larger than an octave. It may be exaggerated and may be held for longer than marked.

Glissando

A glissando is a smooth approach between two notes. Like falls, the original note will be held for a period of time before beginning the glissando. The two notes may be connected via movement through the overtone series, pitch bend, half-valve squeeze or fast chromatic motion depending on the style.

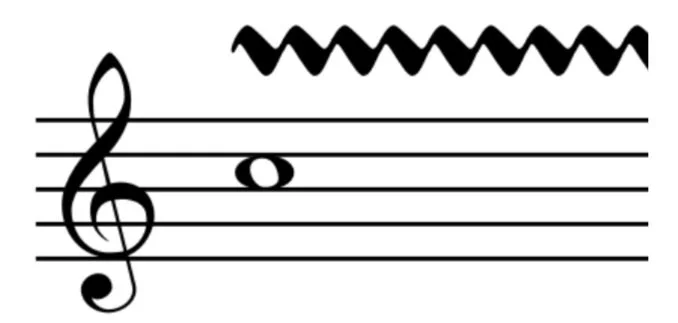

Shake

A shake is a quick trill between two notes. For brass players this is created by a lip trill between the written pitch and the next highest overtone. For saxophones it is a trill between two pitches, usually a minor third. A shake can be quite rapid or slow and wide depending on the interpretation.

Growl

Growling is a technique where the musician vocalizes into the instrument creating a dark and gritty sound. A similar effect can be achieved by using flutter tongue, where the musician creates the growling sound through rapid tongue movements instead of vocalizing.

Bend

A bend is when you play a note and then bend the pitch down as far as a semitone before bending back to the original note. The duration of the bend may be exaggerated.

Subtone

When playing the saxophone, you can alter your mouth shape to create a warmer and sometimes breathier tone. It is primarily used in the low to middle registers and is common in ballads.

The Takeaway

Whether it be harmony, orchestration, voicings, or one of the many other aspects of arranging, when we start writing there are so many areas to keep track of. When I started my journey I fell into the common pitfall of focusing purely on harmony but what I now realize is that there is so much more to writing than cool chords. On this page I hope I’ve helped you see how important range, register, and transposition are as well as introduced you to some fun textures that you have access to in a jazz setting.

Now that we have established a strong foundation to build from, it's time to start looking at one of the most popular sides of arranging: voicings. But that will have to wait for next time as there is quite a lot to unpack!