Everything You Need To Know

About 2-5 Horn Voicings

Whether you like it or not, if you plan to write for more than one harmonic instrument, you’re going to run into the concept of voicings one way or another. The topic is especially prevalent in the arranging world, with content about voicings saturating university arranging classes. Although the information seems to be just about everywhere, it never seems to be explained in a way which relates to the realities of live performance. All too often general voicing shapes are thrown around with context being forgotten entirely.

In this particular resource we cover a whole lot of information. In fact, it may be one of the largest pages I’ve put together on the site. Over the course of the page we will explore voicing techniques for as small as 2 instruments, all the way to as large as 5. Unpacking each combination in a similar manner: first looking at the types of notes you may want to focus on within a voicing, followed by voicing shapes, to then finish by taking instrumental register into account. Hopefully no matter which sort of voicings you’re into, you’ll find some helpful knowledge on the page. Without further adieu, let’s jump into it!

Notes Matter

I was introduced to voicings in a pretty organic way, so much so I didn’t actually know I was using them. When I was at the end of high school I decided to purchase the Sibelius notation software and try and write some music for the band I had put together. With pretty much no music theory knowledge whatsoever, I simply picked the instruments based on the instrumentation of the group and started inputting notes. When it came to harmonizing lines, I would just choose any note that I thought sounded good. Which to be fair is a legitimate approach that guarantees you write music you like.

At the start of 2013 I made the decision to go into the studio and record a few tracks with the group before I moved overseas. However, what made this session even more notable was the fact that I had given myself the goal of writing some of the charts for the ensemble and not solely rely on the jazz standards we had been playing. Unaware of it at the time, this was actually my first dive into the world of arranging.

Being a young bassist, I was completely obsessed with Jaco Pastorius so naturally I wanted to record one of his songs. For those that don’t know me, I love finding almost unknown gems in artist discographies, so when I selected one of Jaco’s tunes it was some obscure track titled Domingo. At the time all I could find online was a big band score so I decided I’d try to reorchestrate the parts to fit the sextet format of my group. I took melodies and added harmony but with no real idea of what was working or not. I simply used my ear which led to most of the horn parts being harmonized in 3rds. Later on I revisited the score and found out I had gotten extremely lucky and made some great decisions by using certain extensions. Remember, at the time I didn’t even know what a 9th was let alone an altered chord.

A few years later I had the chance to learn arranging in a formal capacity, where I was introduced to many different voicing options. It was as if the world had completely changed. Now I understood what notes to harmonize, when to leave out certain notes, and the impact of adding different color tones. Before too long I got stuck into applying them and my arrangements drastically improved. I no longer relied purely on my ear to search for options and could jump straight into a few techniques before working out which ones I liked. As a result, my entire workflow got a lot quicker and I found options I was happy with sooner.

The first approach which changed my outlook on voicings was the idea that you didn’t need to voice out every single note in a chord. Up until taking an arranging class I didn’t realize there was a hierarchy to the notes within each chord. I also never took into consideration the fact that most times when you voice out horn parts that there is an accompanying rhythm section. Or more specifically, an accompanying bass note and harmony part.

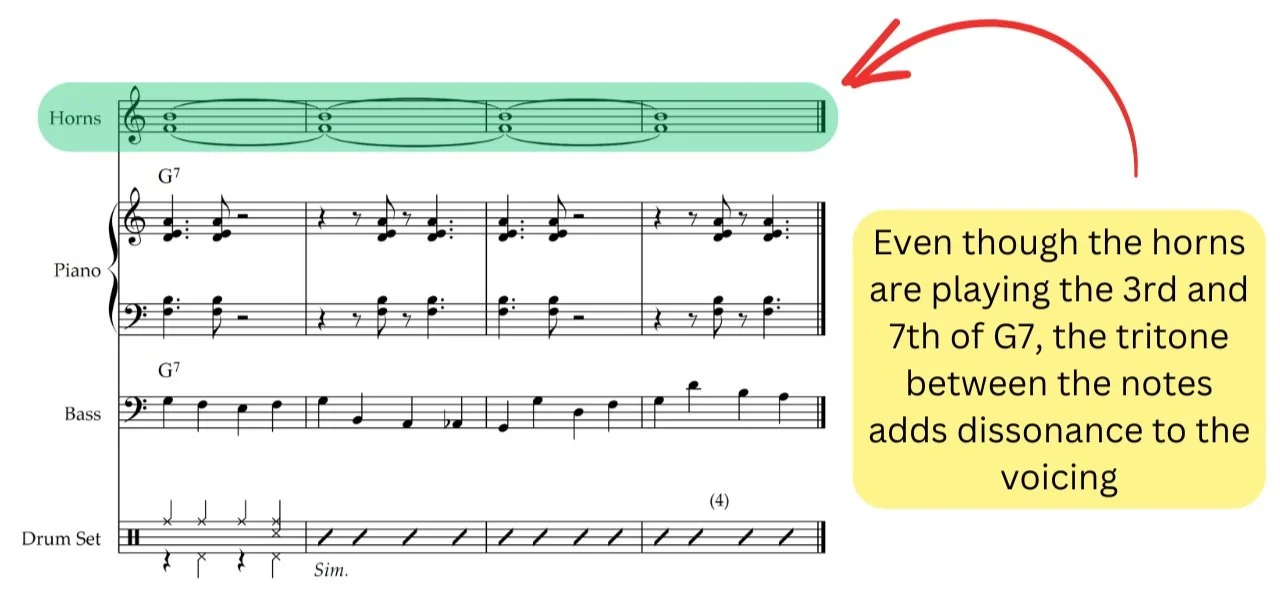

Looking at a 7th chord, you have the root, 3rd, 5th, and 7th, but out of those four notes only the 3rd and 7th really imply the quality of the chord. So if you are looking at representing the sound of a chord, as long as your voicing includes those two notes you will be set. That allows a lot of options when dealing with multi horn voicings as you can start to use extensions and alterations. For example, in a G7 voicing you’d only need to voice the B and F to capture the quality of the chord.

Additionally, the root note ends up becoming redundant due to having an accompanying bass in the rhythm section which again opens up a lot of options. In general when we leave the root out of a voicing we call that a rootless voicing, a technique which you will see is quite common. The 5th is what I like to call harmonic padding. It doesn’t add too much to a chord but is slightly more worthwhile than the root. However, that changes when you have an altered 5th which is far more colorful and would be considered in a similar fashion to an extension.

That leaves us with a basic hierarchy of notes to include in a voicing: 3rd, 7th, 5th, root. Of course this is only when you are wanting to capture the quality of a chord and as soon as you imply any sort of context this hierarchy will be affected. But don’t worry, we will get into that shortly once we explore the different options at our disposal for 2, 3, 4, and 5 horn voicings.

The main reason I started with this area is so that you can see that not every note within a chord is equal and that if you choose to use certain notes or omit them, it will impact how the quality of the chord will sound. Very quickly you will discover that voicings come with compromises. Sometimes you want the quality of the chord to sound a certain way, which is what I call the vertical approach due to the notes being stacked vertically on the score, and sometimes you focus on register or horizontal motion (individual instrument lines more than how they are harmonized). When you’re lucky everything will line up perfectly and you wont have to compromise on anything. It’s those moments we all look forward to and cherish.

It Takes Two

Harmonizing two instruments may be one of the hardest tasks in arranging. You have so many options and due to the nature of only having two horns, everything is out there in the open and feels quite revealing. Although having more horns might seem harder when you’re just getting started, it is far easier due to the ability for a lot of horns to be hidden. A luxury unavailable to us in 2 horn writing.

For many years after I graduated from university I actually never used 2 horn voicings. Not because I didn’t know how, but because I was lucky enough to write for larger bands. Occasionally I would feature two instruments or two part harmony within the context of a big band but it was something I did rather infrequently. That all changed when the 2020 pandemic hit.

After a number of months in lockdown the musicians of Melbourne were finally allowed to perform for live audiences again however with a catch. Ensembles had to be restricted based on both stage and venue size, and if you know anything about the size of jazz clubs, that meant no big bands. This led me to rewrite a lot of my repertoire, reorchestrating it down to a quintet with two horns. Quite a large task and one which forced me to put some serious time exploring 2 horn writing.

If you’ve attempted to write for two horns before, you’ll know that your options are rather restricted. You can’t fully realize a chord with multiple color tones let alone the fundamental notes and if one of the notes is already being used as a melody note it severely limits your options. When I first started writing for the smaller group, I used my normal approach at the time of thinking vertically and just trying to land on interesting chord tones within a given chord symbol. However, after the first gig I quickly realized that for the most part this sounded terrible due to one key factor: a horn voicing is not just an extension of the harmony played on the piano or guitar but also its own entity. For example, I voiced the two horns on the 3rd and 7th of a dominant chord so that it would imply the quality of the chord. Instead of hearing the horns as an extension of the harmony, what happened when it was played live was that I had written a big fat tritone which added a considerable amount of dissonance to the moment.

Shortly after the gig I went back to the drawing board to find other qualities that I could lean on instead of big block voicings. By having only two instruments you can experiment more with the intervallic relationship between the horns, creating color through the tension of certain intervals. You can also look at both parts more melodically, justifying odd voicings through the horizontal motion of each instrument. There is also a certain flexibility two horns allows where you can’t really be bogged down with too much harmony simply because of the lack of instruments.

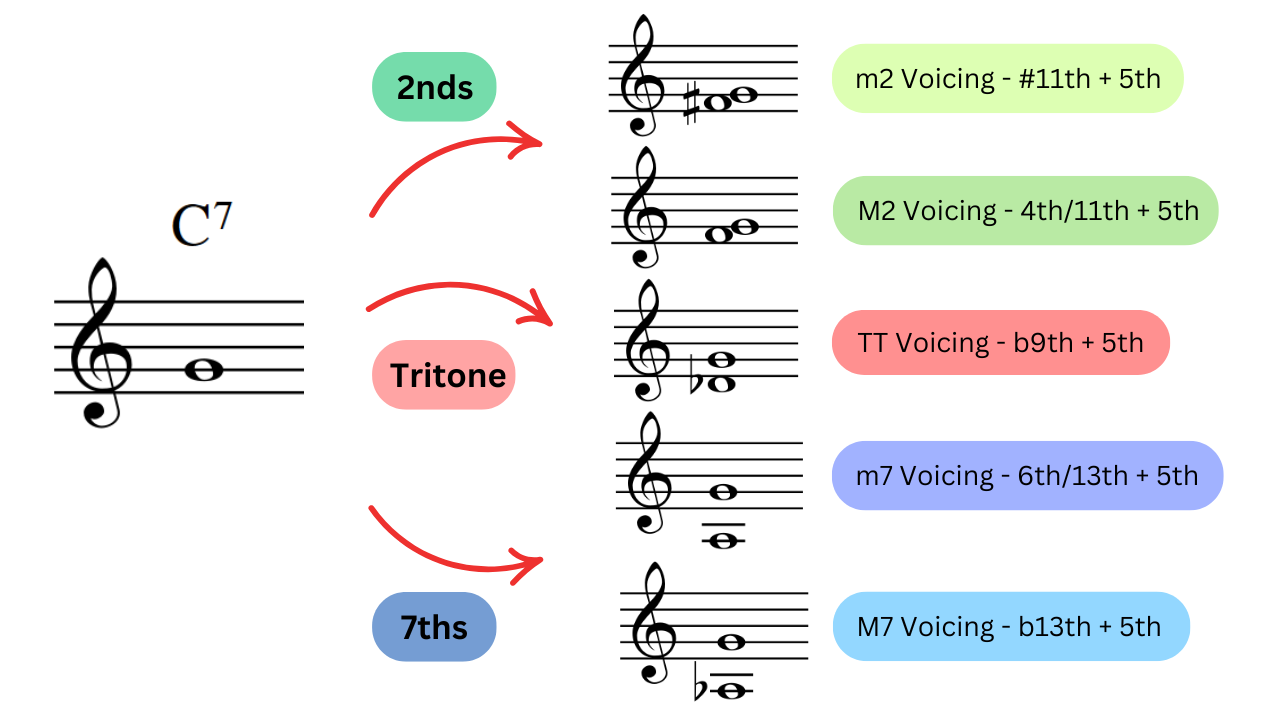

Similar to what I mentioned in my resource on intervals, I generally group intervals into three categories: Consonant, Open, and Dissonant. Unison/octaves, 3rds and 6ths are consonant and stable, 4ths and 5ths are open and stable, and 2nds, 7ths and tritones either feel dissonant and unstable or can take a harmonic padding role such as the case with a m7. When we voice for two horns we have to be aware of both the intervallic relationship between the horns as well as how each note relates to the accompanying chord symbol. However, one area we don’t really need to focus on is fully representing the chord symbol in the voicing due to the limited number of voices available.

Unison/Octaves

If you’re just starting out with 2 horn voicings, a great place to begin is with unison and octave writing. It may seem a bit odd if you have come here wanting to know how to harmonize but unison/octave writing is extremely useful and is quite common throughout jazz recordings. The best part about it is that you know the notes are going to sound great and it puts more emphasis on other elements of the music such as the timbre of each instrument. Whether it was Art Blakey and Jazz Messengers, Dizzy Gillespie, or Lee Morgan, all of them have used octaves and unison heavily in their writing.

Dat Dere

Bobby Timmons

3rds & 6ths

Moving from unison/octaves the next intervals to explore are 3rds and 6ths. Due to their stability they are generally quite safe to use but can also add a slight amount of color depending on which notes you pick. Just to clarify, when I say 3rds and 6ths I don’t mean those degrees of a chord, I mean the relationship between the notes the horns are playing. For example, say you have a melody note that is a G, you could harmonize that with either a B, Bb, E, or Eb if you wanted to use a 3rd or 6th voicing. Now if we zoom out one step further and add a chord symbol, we can relate those notes to the particular chord. For instance, if the chord was a C7 with the melody being a G, then the B may not be a feasible option as it’s the major 7th of the chord. However, the Bb (m7), the E (3rd), and the Eb (#9) would all be feasible. In fact, the Eb would add a layer of color to the chord while still having stability between the horns.

Drum Thunder Suite (Excerpt 1)

Benny Golson

4ths & 5ths

Unlike the other options, 4ths and 5ths give a more modern sound due to their open nature. I consider them just as stable as 3rds and 6ths but with a more unique edge. They are a wonderful choice and one which has been used considerably in modern jazz as well as in the various small groups associated with the Blue Note record label.

Drum Thunder Suite (Excerpt 2)

Benny Golson

Politely

Bill Hardman

2nds, 7ths & Tritones

That leaves us with the dissonant intervals, the 2nds, 7ths, and tritone. I generally use these in two ways, either as a moment of tension where I purposely lean into the dissonant rubs they create, or as some kind of passing motion where they are not heard as much vertically as they are horizontally. The first option operates in a similar manner to the other options we have just looked at where we simply voice out the two instruments using one of the intervals. For example if the melody note is a G, then the options would be Ab, A, F, or F#. You then check these options based on the accompanying chord symbol to see which is feasible.

Drum Thunder Suite Excerpt 3

Benny Golson

The second method of using dissonant intervals is where things start to get interesting. Instead of thinking purely about 2 horn voicings as vertical instances, we can take a more contrapuntal approach using target notes. Although this topic starts to stray away from voicings and will be covered in a different resource, the main point is that you can justify interesting note choices through each independent horizontal line. How I do this is by picking a target note that I want to resolve to, generally some sort of stable interval, and then work backward creating interesting pathways that make more sense from a melodic perspective than a vertical one. I love using chromatic motion as it creates such a strong pull to the target note and often results in unusual voicings which I may not come across otherwise. Due to the complexity of trying to describe an example like this purely by text, I’ve left it up to the graphic below to explain it with the aid of visuals.

Are You Real

Benny Golson

Register

Before we depart from 2 horn voicings there is one last area that needs to be addressed. We now have looked at the various intervallic voicings, how they sound, and how to go about relating them to accompanying chord symbols, but I’ve left out a crucial piece of information. Picking out notes is only one part of finding a great voicing, the other is making sure it lands in an appropriate register for each instrument. Before reading on, if you haven’t read my resource on instrument registers, I’d suggest taking a quick look at it so that you have a better understanding of what I’m talking about.

So often we think about voicings as shapes that can be applied anywhere but in reality, the instruments which you voice out are affected by where in the register you place each note. For example, if you are voicing out a trumpet and a tenor sax in unison, the tenor sax will be higher in its overall range meaning that it will naturally project more than the trumpet even when playing the same dynamic. If you wanted this, perfect you don’t need to go any further, however if you wanted the trumpet to be more present or for the horns to be more balanced, you may need to look at a different voicing.

It should also be mentioned that the orientation of voicings can impact how they sound. For example, if you choose to voice above the melody note there is a strong chance that the new note may come out stronger than the melody. It is more common in jazz for horn voicings to have the melody note at the top, however there are numerous examples of this not being the case and working just fine. The main point to be aware of is the register of the instruments you are voicing out. If the note above the melody is voiced in a lower register than the instrument playing the melody, you’ll have no problem. Additionally, you can put different textures on the note to help differentiate the sound from the melody too, such as a mute.

Unfortunately register is one of those areas where you need real musicians to hear the effect. Whether you use the piano, a DAW, or a digital notation software with MIDI, all of the common playback devices don’t account for this phenomenon. What that means is that you just have to remind yourself of it as you write. If you have the luxury of having a few musician friends, write for them and see how register impacts voicings. After a while you will start to feel more comfortable with it.

The Three Amigos

The process of voicing for three horns is not that much different from what we just looked at with two instruments. All of the same processes exist but we get a few more options due to having an extra instrument. A great place to start with 3 horn voicings is simply to use 2 horn voicings with a doubled note. There’s nothing wrong with using any of the voicings we just mentioned. Just because they are 2 horn techniques doesn’t mean they won’t work for larger amounts of horns. The only thing to be aware of is that when you do so you are left with an extra instrument that needs to be assigned a note.

To deal with this extra horn, the only option you have is to double one of the two existing notes either in unison or octaves. In general the most common option is to double the melody note because any note that you double brings more attention to it. If you were to double the non-melody note, you would be taking attention away from the melody. This can be a useful device in some situations where you want to highlight a counterline or a particular note within a chord, so both options are quite viable. Just be aware of why you are doubling a certain note and the effects it has on the music.

Triadic Voicings

By adding an extra horn into the mix, we now have the ability to create three note voicings. As such, there are a number of different ways to approach the extra note with some being more versatile than others. Coming out of “jazz school,” I took the usual route and followed conventional piano shell voicings to begin with. The sort of voicing which has the 3rd, 7th, and some extra note in the mix, usually a 9th or 13th. However, these can be less than ideal for a number of reasons and definitely not where I suggest starting.

The same year I graduated from college I started playing on cruise ships and inevitably began writing for the artists on board. The most common horn format for cruise ships is 3 or 5 horn so I was able to spend a lot of time experimenting with voicings. Thinking I knew what was best, I focused on the piano voicing style regardless of the style and instrument layout. Sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn’t, but more problematic was the fact that I wasn’t paying attention to how the horns sounded.

Like I previously mentioned, when I came out of the various pandemic lockdowns I had to rewrite the book for my band. At first it was a two horn layout but as soon as the restrictions lifted a little further I expanded it to three horns. With the newly found realization that the relationship between the horns mattered just as much as how the notes related to the chord symbol, I looked at how that may impact 3 horn voicings. Interestingly, there were stable and unstable voicing shapes and you know what, the piano shell voicings I once used often landed in the more dissonant unstable territory due to how each horn related to one another.

With that discovery I started simplifying my voicings, focusing on stable structures that were easy to balance and tune, and most importantly didn’t add any unwanted dissonance. The first shape was built around triads. Whether it be major or minor, a triad is a very stable combination of notes which doesn’t add tension and is common enough that most horn players feel comfortable harmonizing with it. In general, major triads are the most stable, followed by minor and then both augmented and diminished.

Now I want to clarify that even though I say triad, that doesn’t mean it has to be the root, 3rd, and 5th of a chord. It can very much be any set of chord tones which make a triad. For example, in a G7#5#9 you can create an Eb major triad with the #5 (Eb), root (G), and #9 (Bb). That way you have created a very colorful voicing which lands on prominent alterations but also has the stability due to being in a triadic structure.

The Murphy Man Excerpt 1

Lee Morgan

This Is For Albert Excerpt 1

Wayne Shorter

Open & Closed Voicings

Triadic voicings are also a great place to introduce the concept of closed and open voicing shapes. A closed position voicing is any voicing which places chord tones as close as possible within an octave. For example, a C triad would have three possible options, C E G (root position), E G C (first inversion), G C E (second inversion), all of which feature the three notes as close together within an octave.

Closed voicings are often our go to as arrangers because it is easy to see exactly what is happening harmonically and come from a time where arrangers played the piano and could play the full voicing with one hand. On the fip side, an open voicing is a variation where every second note is dropped by an octave. For example, if you had a C triad in root position C E G, E would be dropped down an octave as it is the second note, resulting in the new voicing being C G E. If we continued the voicing down you would skip every second note to get C G E C G E etc.

As we explore more complex chord structures in jazz, creating open voicings using this method becomes problematic due to the number of extensions and alterations that are commonly used. However, when looking at 3 horn triadic voicings this is not an issue and open voicings can be used especially to create stable shapes that accommodate multiple registers.

Quartal & Quintal Voicings

There are also stable options which aren’t triadic, such as quartal and quintal voicings. These take the same concept as the 2 horn voicings built from 4ths and 5ths but add one more open interval to the mix. Like the 2 horn equivalent, these feel more modern due to the open nature of the intervals. To use the shape all you have to do is stack 4ths or 5ths on top of one another. For example, if you had a C melody note then you could either have a stack of 5ths going Bb, F, C from the bottom up, or a stack of 4ths going D, G, C from the bottom up.

The Murphy Man Excerpt 2

Lee Morgan

“Jazz” Voicings

Moving away from stability, the next technique focuses more on representing the quality of a chord symbol. It’s the approach I mentioned earlier which is built from piano shell voicings. With this technique you typically pick out the fundamental notes and then add a color tone. That means that voicings include a 3rd, 7th, and either a 9th, 11th, 13th, or some sort of altered tone. Due to the intervallic relationship between the notes, generally these introduce a lot of dissonance and may not be the most stable shapes. However, they do add a lot of color and tension and can be great for certain situations. In general I refer to these as “jazz” voicings to differentiate them from the others on this page.

This Is For Albert Excerpt 2

Wayne Shorter

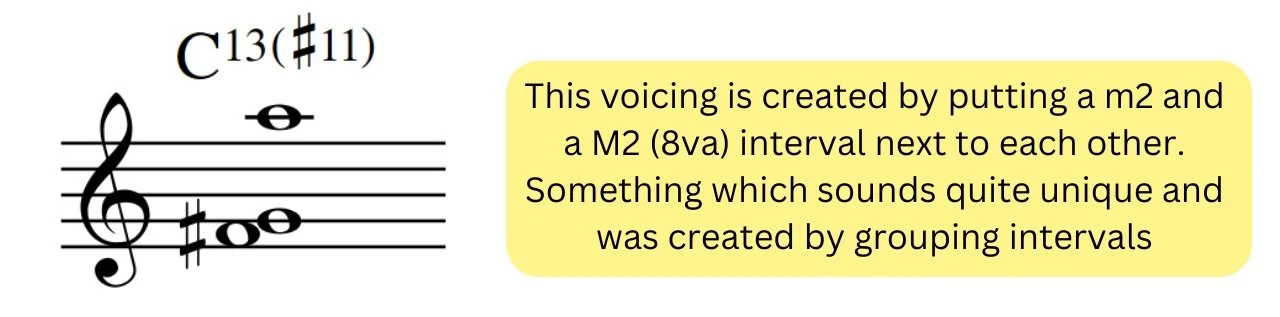

Intervallic Voicings

Finally, the last technique available to you can feel somewhat random and that is to create voicings out of interval combinations you like the sound of. This is quite a creative approach to voicing and one which is mainly used in non-diatonic music, but is still worthwhile to mention. Instead of opting for specific chord tones or stable shapes, you can create voicing purely by combining intervals. For example, you might like the sound of a cluster of m2s, or a big stretch of 6ths, or even a combo of a m2 followed by a M7. All of them are legitimate and can add quite a different feeling to a piece. However I would proceed with caution as this sort of voicing often doesn’t feel too compatible with diatonic music.

Speak Like A Child

Herbie Hancock

Register

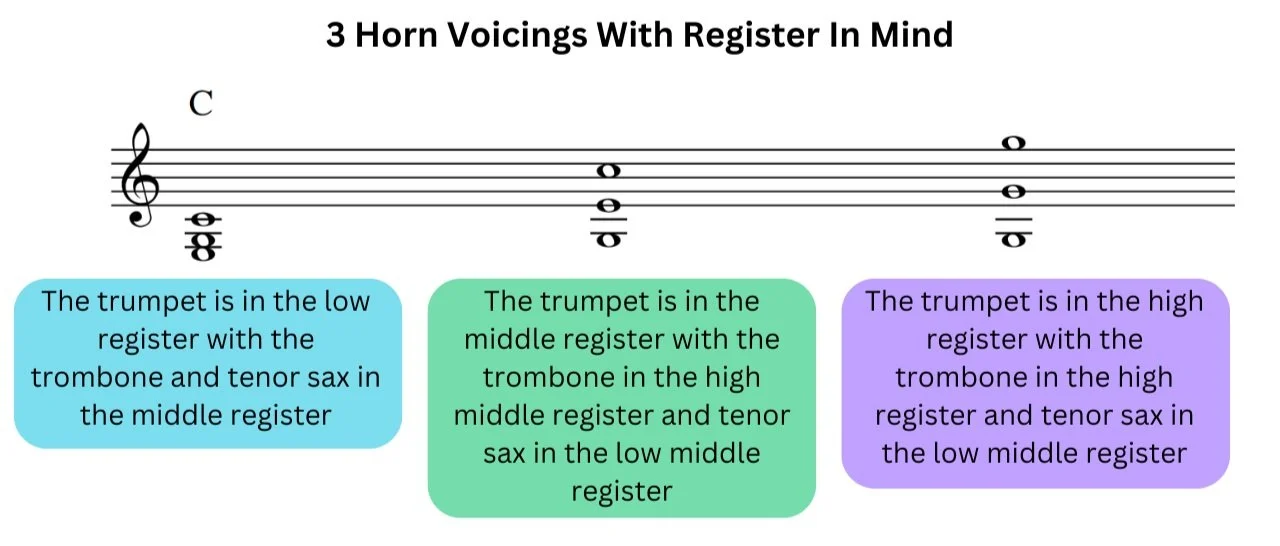

As we did earlier with 2 horn voicings, 3 horn voicings should also be looked at through the lens of instrument register. By simply adding one horn to the mix, register has an even greater chance of impacting a voicing. We’ve already discussed one potential solution being open voicings, so let’s explore the technique a little further but this time with specific horns in mind.

The most common three horn format is trumpet, trombone, and tenor sax which features one soprano instrument and two tenor instruments. As the trumpet’s range naturally sits an octave higher than the other instruments, closed position voicings become quite problematic. To tackle this we can either choose to use large open voicings or rely on simpler options such as octaves or 2 horn voicings. In my own writing I will opt for triadic voicings when the trumpet is in its low register, open voicings when it is in the middle register, and octaves or an octave and a 6th when the trumpet gets too high. That way everything feels stable and the trumpet gets as much support in the high register as the other two horns can provide. If you wanted to highlight the tenor sax or trombone all you’d have to do is make sure its note was in a higher register than the trumpet.

Four & More

You guessed it, up next is 4 horn voicing techniques. Similar to how we started the previous section, 4 horn techniques build off of everything we have just learned. You can use any of the previous techniques with four horns, the only difference is that you will have one extra instrument that will double a given note. However, that extra horn also adds more complexity into the mix and access to even more techniques.

Four Note Closed Voicings

For the first time on this page, by having four horns we can now create stable voicings which include the fundamental chord tones and some sort of color tone. Not every situation will allow for this with the melody note playing a large role in what is possible, but we finally have enough instruments to even consider this option. So what does it actually look like? Well for the most part it will be a triadic voicing for three instruments with an extra tone added into the mix. For example, if you had a G9 you could have a D minor triad (5th, 7th, 9th) and the B (3rd). As a result you would have a rootless voicing which would have the functional notes of G7 as well as the added color tone. Looking back to the definition of closed voicings we touched on earlier, this new four note chord is also a closed voicing and is actually the most common type of closed voicing you’ll encounter in big band arranging.

Katy Do

Benny Carter

Quartal & Quintal Voicings

We can also keep using quartal and quintal voicings but this time with a stack of four notes. With this many notes it is actually possible to also highlight fundamental chord tones and color tones. For example, if you have a Cm7 chord you can have a 4 horn quartal voicing starting on the root which hits the 3rd, 7th, and 11th giving you the voicing C F Bb Eb. With so many notes it can also be necessary to invert some of the voices, giving a number of different variations all built from the same approach.

The Hills Are Alive

Arr. Toshi Clinch

Spread Voicings

Another approach to 4 horn voicings is to have a much larger spread of notes built on the concept of having the fundamental harmony at the bottom and the extensions above. Depending on which instruments you are using, sometimes you can have a two octave spread between notes allowing for a lot of options. For example, if you have a G7 you would voice the 3rd and 7th within the first octave and then any sort of extensions in the octave above. If you’re lucky, this sort of voicing can sometimes be an open voicing which is quite stable, however it is not always the case.

Pop Voicings

When I think of four horn sections the first name that comes to mind is Jerry Hey and the numerous recordings he has done over the last 50 or so years. If you YouTube any of the live session videos of the Jerry Hey horns you’ll notice they use the common setup of two trumpets, trombone, and some kind of sax but usually tenor. However there is a little bit of trickery taking place. By being in the studio they have the chance to overdub parts and if you look hard enough you can find interviews of Jerry actually saying he voices those classic horn parts more like a big band than a typical four horn section. I mention this because if you’re like me and love that type of horn writing, if you are trying to capture it with only four horns in a live setting then the end result will be a bit different to what you hear on the records. That’s not to say you can’t get some amazing 4 horn voicings that work really well, they just may not have the depth that classic Michael Jackson or Earth, Wind & Fire horn parts have.

The key to making them feel balanced is to once again revisit the idea of register. With four instruments you can use a lot of different approaches which may be a bit confusing to begin with. A great way of tackling so many different voices is to first look at the register of the instrument taking the melody note and to decide whether you want that to be the most prominent voice or not. With that decision in mind, you can then start looking at where the notes of the chord land in the registers of the other instruments and compare that to the melody. Don’t be afraid to use simpler voicings which may not include color tones, sometimes more complex chord shapes aren’t even possible due to the context.

Take Five

Congratulations, you’ve made it through a huge amount of information and have finally arrived at 5 horn voicings. The bad news is that we still have a monumental amount of methods to cover but I’m guessing if you’ve made it this far that you’re the sort of person that wants to learn as much as possible about voicings. If so, you’re in for a treat because 5 horn voicings not only build off what we have previously mentioned but also introduce a whole lot of new techniques into the mix.

Four Note Closed + Octave

Like every section before this, 5 horn voicings can be built from every single approach we have already covered just with an extra doubled note. In fact, the most common way of voicing five horns is what we called a four note closed with an octave double. That’s when you create a four note closed voicings like we explored with 4 horn voicings, and then simply double the melody note in the 5th voice down an octave.

When You Wish Upon A Star Excerpt 1

Arr. Toshi Clinch

Independent Voicings

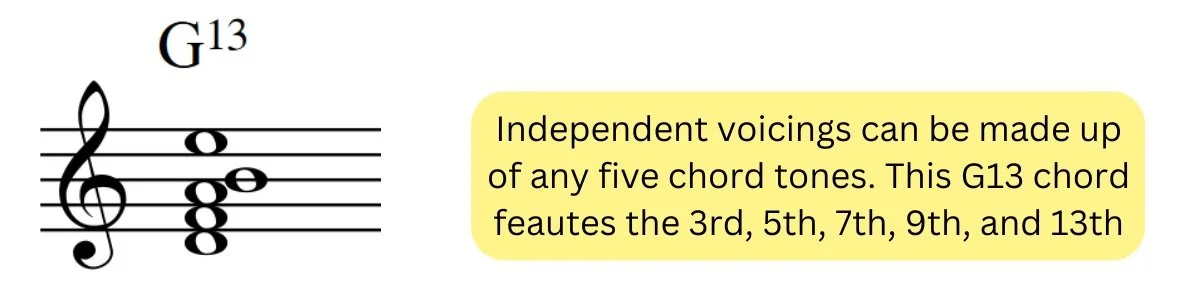

Another common approach is called an independent voicing, where all five notes are unique. Some of the techniques covered thus far can be classified as independent due to having all different notes, however when I learnt about voicing I was introduced to the terminology in the context of five horns. Either way, as long as you associate the word independent with a voicing which has no doubled notes that’s all that matters. Independent voicings are quite flexible and can be in a closed position shape within an octave, or spread much larger.

The best aspect of these types of voicings is that you can almost always adequately capture the full sound of a chord quality. Maybe with the exception of 8 note chords such as Dom13(#11b9#9). With five notes you can easily feature the melody note, the 3rd, 7th, and two extra tones, giving you lots of options to play with. If you want the chord to be more colorful you can assign the extra notes to extensions or alterations, or if you want it to feel more foundational you can pick the root or 5th.

Avenue C

Buck Clayton

Drop 2 & Drop 2+4 Voicings

With so many instruments at our disposal we can make use of closed voicing variations such as drop 2 and drop 2+4. These fall into a category somewhere between traditional open and closed voicings as they share traits with both. A drop 2 voicing is when you take any closed voicing and drop the second voice from the top, down an octave. Whereas a drop 2+4 does the same but with the addition of the fourth note from the top. The main purpose of these variations is to help spread out a voicing into a lower register for the inner voices. It is particularly useful for mixed sections such as when trumpets are paired with instruments like trombones or tenor saxes which have a range an octave lower. This allows the voicing to still feel balanced when the trumpet is entering a higher register.

Bali Ha’i

Lennie Niehaus

Quartal & Quintal Voicings

Even though you have five instruments you can also still use quartal and quintal voicings however, if you invert them they often start looking like other types of voicings. As we explored with four horns, the notes started representing chord tones even though they had been chosen because of the voicing shape rather than the chord symbol. By having five instruments you are even more likely to land on both functional chord tones and color notes. The voicing shape still gives a more modern sound and with so many voices you really need a mixture of different instruments in order to span such a large amount of distance.

Three Views Of A Secret

Arr. Toshi Clinch

Spread Voicings

We’ve got one last similar technique before moving on to new ground, and that is that you can use the wide spread method with five horns too. In fact, having five instruments makes it even easier because there’s more chance you can create a stable set of internal intervals while voicing the fundamental notes lower and the color tones higher.

‘Round Midnight

Arr. Toshi Clinch

EQ Voicings

By having the luxury of so many instruments we can start to think about larger implications of the voicings we use. Simply by having such a mass of voices we can create unique feelings that aren’t possible with smaller horn sections. However, it took me a number of years to realize this and up until 2021 I just applied basic voicing techniques without giving it much thought.

When I came out of university in 2016 I threw myself at the world, wanting to write as much music as possible and achieve big things. Looking back, I consider myself extremely lucky because I was able to successfully accomplish those ambitions. However at the time I definitely was quite green, thinking that I knew everything about writing and that nothing could stand in my way. Truth be told, I only knew the theory behind writing and needed to get some real world experience to actually understand what I had learnt in school.

Early on in my professional arranging journey I was given the opportunity to write for a reduced big band where I transcribed the classic repertoire of Basie and reorchestrated it for the smaller sized ensemble. Without too much thought, I plowed through the work and voiced everything in stock voicings, whether that be closed position or drop 2 and drop 2+4. After writing a concert's worth of music it came time to perform the freshly printed charts. At the time I thought everything went smoothly but afterwards one of my closest friends Niels Rosendahl, an exceptional musician/writer who happened to be playing sax on the gig, mentioned that I had written everything in the high register which made the entire set feel very bright. Knowing Niels, even though I’ve forgotten his exact words I know it was said in the nicest way possible, but regardless, I let my ego get in the way and discarded his view.

I continued to write in this fashion for a number of years until I was inevitably stopped by the global pandemic of 2020. For one reason or another, this forced break led me to contemplate how I approached writing and make changes. With the lockdown restrictions slowly easing, I got back to writing and had the opportunity to rewrite the music for my 5 horn youth ensemble. As I’ve mentioned earlier, the process of orchestrating the charts for 2 and 3 horns gave me a new perspective on the impact of register but it wasn’t until I started rewriting the parts back to the full 5 horn capacity that the words of Niels all those years earlier started to resonate with me.

I made sure to take the time and look at the parts I had once written and analyze how they sounded. How they made me feel. And what would you know, almost all of the full horn moments were extremely bright due to the voicings pushing every instrument into the upper register.

After reworking the charts I learned that you can EQ a horn section by the voicings you use. If you want it to feel bright, you can bring them all up into the upper register. If you want it to feel balanced, you can spread the voices out equally among the low, middle, and high registers. If you want it to feel murky and dark, you can focus more on the low register. Admittedly, this was something I had been taught at university in the context of big band writing but I had never really taken the same approach to smaller formats. It may have taken 4 years, but by finally listening to Niels’ wisdom I had learned a new way to approach 5 horn voicings.

Why don’t we have a look at this in practice? Using the same G13 chord and instrumentation, here are three different approaches which have unique feelings due to the register of each note. Please note that the aural effect of this technique will not come across with MIDI tracks to the same extent as real life.

Splitting The Section

When we have a mixture of different instruments within a 5 horn voicing, it allows us to split the section into smaller groups. For example, if you had two trumpets, trombone, alto sax, and tenor sax, you could divide the section into brass and woodwinds. This can be a great way of grouping similar textures or assigning countermelodies. To deal with the voicings, all you have to do is simply think of the new smaller sections as being their own group. In this case you would think of the brass using 3 horn techniques and the saxes using 2 horn methods. There’s no limit to how you want to break down a section and if you feel very adventurous you can even look at it as five individual instruments that are playing contrapuntally.

Friend Like Me

Arr. Toshi Clinch

We Don’t Need No Rhythm Section

Up until this point we have been looking at voicings within the context of having an accompanying rhythm section. However, you can also write for horns in an acapella format if you prefer. The main difference is that the root of the chord needs to be incorporated into the voicing. Otherwise the music will take on different qualities that are more strongly associated with rootless voicings. For example, if you had a G7b9 chord you’d most likely voice the notes B, D, F, and Ab when the rhythm section is playing. As soon as you remove the rhythm section you’re left with a Bdim7 sound which gives off a different feeling compared to the original G7b9. In order to accurately represent the original chord symbol the voicing would need to incorporate a G somewhere. Thus giving you a G7b9 in some sort of inversion.

Depending on the instrumentation, you may have some horns which can enter the bass register. In which case you can assign the root note to them to more accurately represent the chord. This works particularly well if using the bari sax. When voicing the root note in this way, you can think of the note as being somewhat free from the voicing structure above. Usually we try to create resolutions with minimal movement between chord tones, however the root note is the exception and as a society we have found it completely acceptable for the bass voice to jump around the place when necessary.

Li’l Darlin’

Neal Hefti

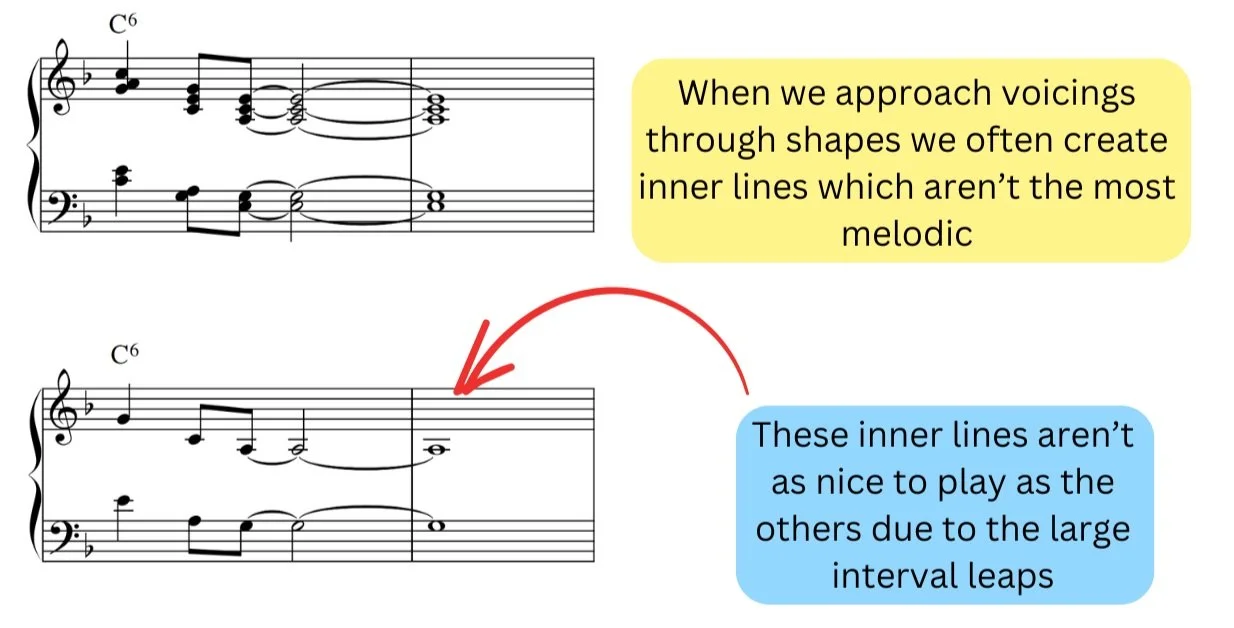

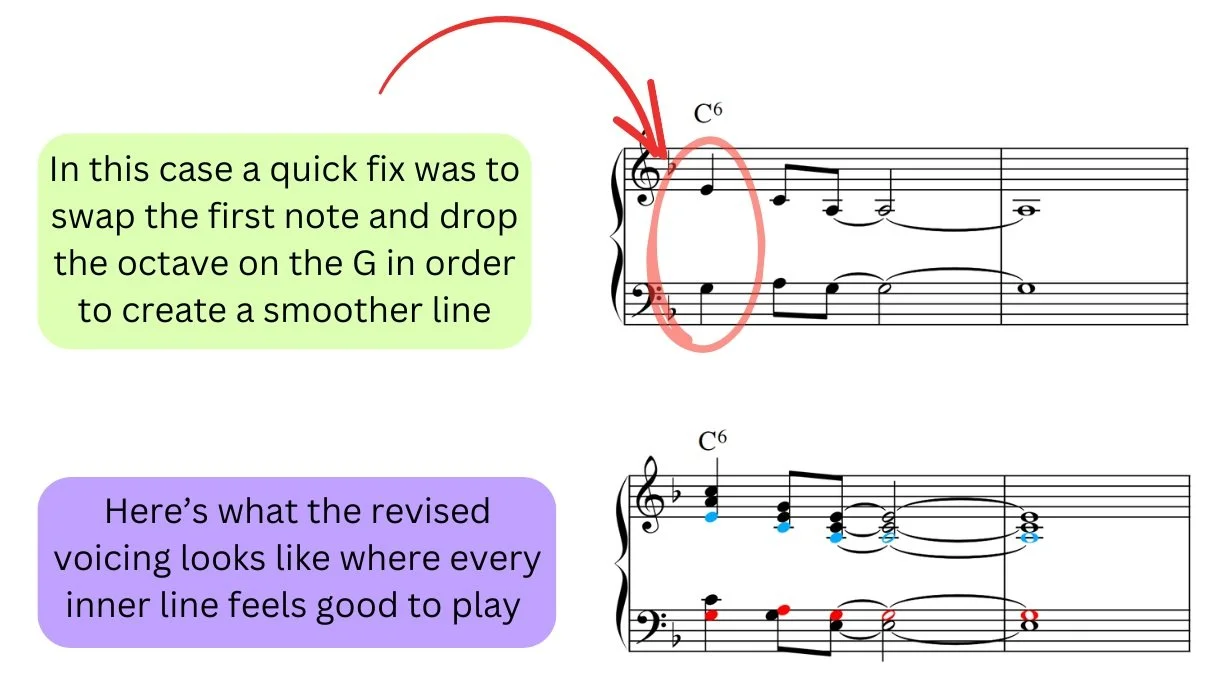

Horizontal Voicing

Moving away from vertical techniques, you can also approach voicings by the individual lines that the instruments are playing. Typically when looking at voicings in this way, the vertical nature may become simpler and not necessarily reflect all of the notes in a given chord symbol. The upside is that every musician will have a much nicer part and be able to play everything more musically.

To think horizontally you will need to look at the individual lines of each of the instruments you are voicing for and pick notes that both work within the given chord symbol and sound good melodically. If you had to prioritize one over the other, I’d suggest the melodic approach as the strength of a melody/countermelody generally is more important than nailing chord tones. Due to this being a difficult technique to explain via text, here is a series of graphics depicting the process.

When You Wish Upon A Star Excerpt 2

Arr. Toshi Clinch

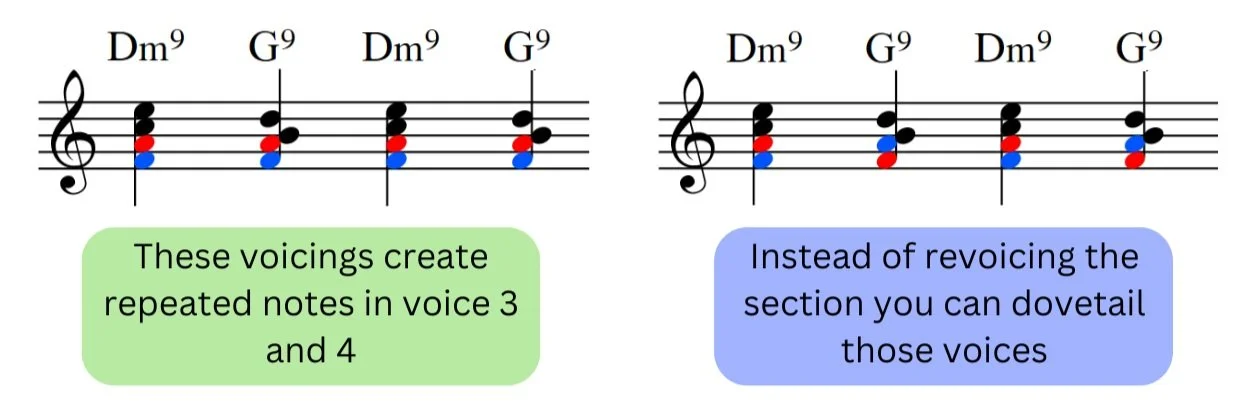

Dovetailing

By checking each individual line within a voicing, you can make sure that every instrument’s part makes sense and feels great to play. A common occurrence when voicing out multiple notes in a row is creating repeated notes in the inner voices. Sometimes this can work but other times it creates an annoying situation that takes away from the person's part. When necessary, you can use a technique called dovetailing to avoid repeated notes, which is when you reassign the inner voices. For example, voice 3 and 4 may be flipped with one another for a voicing before returning to their original line.

Voicing Behind A Melody Line

Generally when we discuss voicings we assume that the melody note is the one being harmonized. However, you can also voice a separate part which happens alongside the melody. The most obvious example of this are horn parts behind a vocalist, but there are many examples and it could be that you split a 5 horn section into a soloist and a backing 4 horn part. Nothing drastically changes in how we approach voicing for these situations except how we might think of the melody note placement within a voicing.

Looking back at the various techniques discussed, the common trend is to place the melody note as the top note of a voicing. However, when voicing behind a melody line you may opt for a different top note that better suits the context. In this case it is suggested that you place the melody note somewhere within the voicing to help reinforce it. If you recall where we started on this page, doubling the melody helps bring more attention to it, and in the instance where the melody is being sung, having it doubled in one of the inner voices can help provide a reference point for the vocalist. Of course you don’t have to do this, just be aware of whether you are bringing attention to or away from the melody note.

Let’s say you have a G in the melody over a C7 chord and want to make the top note of your voicing something different. Using a four note closed position voicing you’d want to get the melody note, the 3rd, 7th, and some other tone in the mix. With this logic you could make a few different notes your top note, with the remaining notes being E (3rd), G (melody), and Bb (7th).

Another option is to look at the instrument playing the melody as being a part of the voicing momentarily. This works a bit better when the soloist is an instrumentalist not a vocalist as the timbre is similar to the other horns. Using the previous G melody note over a C7 chord, that would allow the horn voicing to replace the doubled melody note with another chord tone.

Watch Out For The Mud

Now that we have established all of the different voicing techniques there is one last topic to mention: the bass register. There comes a point where if you voice a chord too low it starts to sound quite muddy. Generally speaking, this takes place when you voice any note other than the bass note (usually the root but could be another chord tone when an inversion is present) below the D in the middle of the bass staff.

Context plays a major part in this rule as the tempo, chord tone, and instrumentation may shift the point where a voicing becomes muddy. For example, 4ths and 5ths generally don’t feel as muddy and can be voiced below the middle D, however more dissonant intervals like 7ths, 2nds, and tritones become muddy almost immediately. If you are writing for a bass trombone or bari sax, they may still be in their low/mid register which won’t feel as heavy as say a tenor sax or trombone. And if the tempo is slower, you can get away with thicker voicings which delve lower into the bass register.

Outside of the bass register, another way of reducing clarity in a voicing is by placing a note a M2 or m2 away from the top note. When the note proximity is this close, the added tension takes away from hearing either note. This can be useful in some situations and less so in others.

Too Many Cheeseburgers

On this page there has been a tremendous amount of information about harmonization. So much so that it will give the impression that you must voice everything where possible. At least that’s how I felt when I first was introduced to these techniques. But I want to remind you of something I brought up when I discussed event lists on a different resource. Voicings can be overused and may also take away from the music you are writing. If you are constantly harmonizing every part, you will eventually reach a saturation point where you have eaten too many cheeseburgers and may need to pivot. It took me way too long to realize this in my own writing.

Sometime in 2016 or 2017 I was given the opportunity to arrange a big band chart for Danilo Perez when he visited the university I attended. Although I was given a short turnaround, I made the most of the time I had and submitted the arrangement to the band director. All was well and good but when I heard the chart performed live with Danilo it sounded quite sluggish. At the time the only thing I was aware of that could cause it to sound muddy was voicing into the bass register. When I got home I immediately checked the score to find that I had never voiced lower than the middle D in the bass staff and was left baffled.

Fast forward a number of years to when I was rewriting my small ensembles book post COVID lockdowns. By having to condense music down into a 2 horn capacity I was forced to leave the voicings I treasured so dearly and looked elsewhere to generate interest. I ended up focusing on individual instrument textures with minimal harmonization. The best part of this process was that I could directly compare and contrast my new versions with the old arrangements. What I noticed was that even without the thick voicings I was able to maintain interest and capture the essence of the pieces. And when I did end up using a voicing, it really shined due to being an outlier, almost as if I was emphasizing it due to the lack of voicings preceding the moment.

Unbeknownst to me at the time, I had actually just stumbled upon the reason my earlier arrangement for Danilo felt muddy. By voicing absolutely everything, it weighed down the music. This was amplified by the fast tempo of the piece, with the harmonization suffocating the whole arrangement. Since my light bulb moment back in 2020/2021, I have purposefully used less voicings in my arrangements, and only when I really want to bring attention to the harmony. Personally I’ve enjoyed the results and feel like I write better music today because of this newly found awareness. I’m not trying to tell you to stay away from voicings, I just want you to know that they are only one part of the arranging process.

The Takeaway

As I mentioned earlier, horn voicings are a game of compromise. You have to work out what you want the most of at any one point in your arrangement, whether that be the vertical shape, the intervallic relationship between the horns, the horizontal motion of each instrument, or the register each note lands in. It can feel like quite a complex puzzle but it’s extremely gratifying when you find a solution you like. Regardless of how many horns you choose to voice for, you’ll have to go through the same process.

On this page I’ve tried to be as thorough as possible and have only included voicing techniques I use frequently. If you were to try and apply all of them practically, it would take years to exhaust the list and be bored of the options provided. With that said, if we look at the specific instrumentation of the big band, that context helps refine the approaches mentioned on this page due to the nature of each section in the band. But that will have to wait for now as this resource is jam-packed enough. Next time I’ll unpack big band voicings.