How To Make Sure Your Arrangements Are

Always Interpreted Correctly

Like many beginner musicians, I didn’t think twice about the sheet music that was presented to me at a rehearsal. All I knew was that I’d show up and play the notes on the page. That started to change as I got older and more experienced. As a bassist, I began noticing how one chart would differ from another, more so the factors I didn’t like such as not including chord symbols on walking bass parts. Then one day I was booked to do a show which featured all of the popular theatrical hits from the last few decades. When I accepted the gig I expected it would be like any other experience I’d had with sheet music but the first rehearsal changed everything.

I set up my instrument and amplifier and patiently waited for the MD to bring around the sheet music. He started handing out everyone’s parts but when he got to me he informed me that there were no specific bass parts and that I would have to read off of the score. My ignorant 17 year old self said that wouldn’t be an issue, having never looked at an orchestral score before. Quite quickly I realized it in fact was a very big problem as I tried to make page turns every four bars through hundreds of pages of scores.

Coming out of that rehearsal I decided to go buy the Sibelius notation software and input every bass part myself for the show only two days away. Somehow with no knowledge of the program and an impending deadline, I got it done in time and reduced hundreds of pages into only a dozen or so pages of bass parts. From then on I realized how important it was to make sure everyone had adequate sheet music. Not every situation would have someone like me who was willing to fix a problem like that, and if they were, then it would likely come at a cost.

In the coming years I started to invest more time into writing music and running my own ensembles. It felt like every time I brought a new chart into a rehearsal I would learn something new. Not only did I have to make sure everyone had an adequate part that was printed, I also realized that I had to include certain details otherwise the musicians would interpret the music incorrectly. Over time those little notes built up and have now created my approach to formatting sheet music.

Unfortunately, many arranging classes simply don’t include formatting as a significant part of the arranging process. As a result, so many writers finish inputting the notes and leave it there, often leading to situations where the players have to pick up the pieces. I’ve been on both sides and I’ve also seen it happen to many inexperienced writers too, and every time I am reminded that it could’ve been avoided simply by spending more time formatting the parts. Remember that it’s no good being the next Mozart if the musicians who are playing your music can’t interpret it.

What you’ll find on this page is a number of areas to look out for when preparing sheet music. This is by no means a definitive list and each year I still stumble upon new ways to improve my formatting. There may be some approaches you take that I haven’t included and if that’s the case, I’d love to hear from you so I can add them here.

Getting Started

When you start out formatting music it can be hard to know exactly what is important to a musician and should be included on a score. However, unless you are approaching engraving without ever playing a musical instrument, you will likely have some preconceived ideas of what you like to see in the parts you play, or maybe what you don’t want to see. The key is to start being aware of these details and trying to implement them into your own formatting workflow.

We can add to this list by looking at published sheet music and try to replicate the decisions they make in our own scores. Perhaps it’s font choice, or orientation, or maybe how the bar lines are grouped. Sometimes you may also disagree with published charts which can be equally as important as it will help you better understand what you don’t want your music to look like.

Another option, and possibly the most helpful, is simply to ask the musicians who are playing your arrangements for their opinion. As they are the ones having to interpret the music, you can edit your parts to best suit them. Not every musician will have the same thoughts but over time you’ll be able to work out what the majority of people need to see for the parts to be interpreted correctly.

So that you don’t have to start from scratch like I did, below you’ll find a number of different areas I focus on when formatting scores and parts. Each of them has come from thousands of real world scenarios and I’ve tried to incorporate as many of the accompanying stories/lessons to help you understand why each area is important. I’ve divided the page into three categories: general - which covers topics applicable to all sheet music, scores - topics specific to formatting scores, and parts - topics specific to formatting parts.

General Formatting Tips

Over the years I’ve been fortunate enough to help many students bring in their first big band chart to a live band rehearsal. It may be somewhat mean of me, but I usually don’t give them any tips for how to format an arrangement ahead of time as any lessons they learn through real experiences have far more weight than anything I could’ve said to prepare them. As such, I’ve been able to see a number of recurring issues between the students, and to my surprise it is often the basics which cause the most problems.

There are many aspects to music notation which seem so simple that they can feel almost redundant to discuss. However, when it comes to formatting, we want to make sure that we understand every piece of information we place on a page and know the reason why we have used it. These include details such as text, accidentals, articulations, phrase markings, and dynamics, all of which play a vital role in conveying information to a musician. If we know how to use them appropriately then there is a far better chance that a musician will interpret our music correctly. Ironically, although these elements are so common, they are also the places where writers make the most mistakes.

Text

One of the biggest areas which needs to be addressed with first-time arrangers is text, mainly because they haven’t included enough of it. When we look at a chart, the easiest way to convey any sort of information is through text. In some cases it can be as basic as the title or composer credits, but in other instances it can include specific techniques, roadmap instructions, and other critical information. Each has its place and works together alongside the music notation to shape an arrangement.

It may seem impossible to forget to include a title and composer credits but I’ve seen it happen more than once. The title is crucial as it is used to organize charts from one another. Imagine you are looking through a school library and are wanting to find a specific arrangement, or perhaps on the bandstand having to shuffle through your folder to pull up the next chart. Well it would be very difficult if the chart you were looking for didn’t have some kind of title. Additionally, the title can offer a glimpse of what the piece of music is about. Sometimes charts have nonsense titles that don’t mean anything but other times they may offer some insight to what the music represents. For example, Rich DeRosa has a composition titled “Perseverance” and the entire composition is built around the idea of replicating the feeling of perseverance. Another example is Drew Zaremba’s “Pistachio,” which is named after a quote from trumpet Jay Saunders and is Drew’s interpretation of Jay’s fun personality.

Alongside the title, you usually include credits. It’s important that we acknowledge who may have written the original melody and/or lyrics for the pieces we arrange. They deserve recognition for their work and if you ever look to sell an arrangement, there are legal ramifications that require the original creators name to be included. Secondly, it’s important that we also include our own names so that others can link the work back to us.

Another crucial piece of text is the style and tempo marking. Again you may be thinking this seems obvious but too many times have I seen amateur arrangers pull a chart up with no indication of either. The style marking helps provide some context for a piece. It can be as simple as “Med. Swing” which gives some indication of time feel and locates the arrangement beside many other jazz charts, or it can be more detailed such as “1920s Harlem Swing” or “Kansas City Jump Swing.” Both of which help imply exactly what sort of swing feel the piece takes on. Depending on how detailed the style marking is, tempo can sometimes be implied. For example, medium swing is roughly in a 100-150bpm ballpark. However, you never know who will be directing your arrangement so I find it is always best to give a specific tempo when possible.

Moving away from the more familiar options, there are many other important ways we can use text to communicate our intentions to the player. One such way is through providing an accurate roadmap of a chart. What this means is to use text any time a player may need clarification around the form such as with repeated sections. For some charts this might look like having “Chorus” and “Verse” marked at the start of the appropriate sections. In other cases it may look like a clear D.C. al Coda or D.S. sign. However the most appropriate time is when you are using repeats.

If you’re like me, then even if you’ve run a chart a thousand times, in the heat of the moment you may forget how many times you need to loop a repeated section. Although the normal convention is two times, there are so many examples of solo sections with open repeats that musicians often look for cues more than actually reading the ink. If you are wanting to add a repeated section into your chart I would suggest using box text to signify how many times you want them to play the section. For example you could say “2x” or “3x” or “OPEN RPT.” By using a box it helps the repetition marking stand out from other text. If the section has background figures that enter, you can also include normal text and say something like “Horn Backgrounds Last X” or “Horn Backgrounds On Cue.” Lastly, if you are using open repeats, to help guarantee as little confusion as possible, you can mark “On Cue” at the start of the next section.

When it comes to confusing musical situations, often they occur when there’s a vocalist thrown into the mix. Back in my cruise ship days there was one such incident with a singer which will stay with me for the rest of my life. It was the welcome aboard show and the cruise director wanted to sing with the band to open up the performance. The rehearsal had gone smoothly but somehow during the show the vocalist and the band got off from one another. The MD frantically tried to fix the situation which only made it worse, and by the end of the piece it was well and truly a trainwreck. Unfortunately on our parts we had no information about the vocal lines and for many of us we weren’t familiar with the song to self correct in the moment.

Coming away from that experience I realized that there was an easy fix that would’ve helped everyone. Simply including the main lyric at the start of each section. By doing so, we could’ve located where the singer was quickly and saved the performance. Since then I’ve made sure to include lyrics alongside section markers such as “Verse” and “Chorus” to help give musicians a fighting chance when crap hits the fan. Furthermore, when there are solo lines that dictate the entry of the band I use cue notation so that everyone can follow the melody in real time. Since then, there have still been many moments when soloists and vocalists have come in early or strayed from the band, but the response time has been much quicker.

Looking elsewhere, text is important when it comes to using mutes and doubles. If you are wanting a brass instrument to use a certain mute you need to mark that with text over the given part. Nothing flashy, just the words “Straight Mute,” where you replace the word straight with whatever type of mute you are wanting to use. When you want the musician to remove the mute you use the word “Open.” It is also courteous to warn a player of upcoming mute changes on their part by using the text “To Cup” or “To Open,” with the word cup being interchangeable with the specific mute.

Be aware that it takes some time to either put a mute into the bell of an instrument or remove it so you should allocate an appropriate amount of rest where possible. In the instance where you need the player to move rapidly, simply add the word “Quick” alongside the mute change warning. All of these options also apply to instrument changes where instead of a mute being marked in the text you use the specific instrument they are changing to. For example “To Alto Sax.” It should also be noted that when you change an instrument you may have to change the key and clef to accommodate the transposition of the new instrument.

A useful bit of text which is often forgotten about is marking the lead instrument in a harmonized section. This is extremely useful for combo arrangements where there may be a mixture of different horns but is also applicable to sections of a big band when the typical lead instrument (Alto 1, Trumpet 1, Trombone 1) is not the lead. For example, if you had a sax section but Tenor 2 was playing clarinet and voiced as the lead instrument, on all of the sax parts playing you’d mark “Clarinet Lead.” For the clarinet part you could also shorten this to “Lead.” When the section eventually reverts back to the standard format, you’d then mark “Alto 1 Lead.” Great players will be able to hear when a lead part changes but by marking it in a part it also helps convey your intention and can stop any bandstand disagreements before they arise.

Another common occurrence is when a melody line is being played by only a single instrument. When this happens, you should mark the line with the word “Solo” to indicate that they have the freedom to interpret the melody as they wish. Other times there may be instances where two or three instruments are doubling the same line and it would be beneficial for the musicians to be aware of each other. In which case you can mark the relevant parts with the text “With…” where you add the relevant instrument afterwards.

Lastly, you may find yourself needing to use text to provide certain information that is unable to be explained in any other way. This is most typical with drum parts, such as if you want them to play in the style of a certain drummer. However, I’ve also used it when I want certain embellishments to be exaggerated, such as “Big Scoop” etc. In these instances we have to find the right balance of providing enough information that the musician understands what we mean but in a limited number of words so that it doesn’t overcrowd the page. My general rule is to use as little words as possible to convey what you want. Nobody will complain if you are succinct but they definitely will if you have a paragraph of text that could be simplified.

When it comes to text we also have the choice of what font we want to use. As a university student I would geek out over fonts all the time and thought a chart looked amateur if it had one of the stock notation software options. These days I don’t care nearly as much, believing that the font doesn’t really matter as long as the message is being conveyed concisely. However, there are benefits to picking your own distinct font. For the past decade I’ve used one primary font for all of my charts and as a result many musicians now can identify one of my arrangements simply by the font and layout of the title. Alternatively, there are many arrangers who use fonts which reinforce the vibe of the chart. I don’t know how well it works but it is an option at your disposal and can be a bit more fun than sticking to the same option every time.

Dynamics

Moving on from traditional text, dynamics are a somewhat special text option which are essential to writing music. So many times I’ve read charts as a bassist only to have no dynamics marked. And it’s not just the bass. For one reason or another, it is quite common for rhythm section parts to be forgotten about when it comes to dynamic markings. With that said, new arrangers have often forgotten to include dynamics across all parts on their first edit, not just the rhythm section.

When it comes to including dynamics we are limited to only a few specific markings to dictate everything between extremely quiet to extremely loud. Depending on the chart, a mezzopiano can mean two completely different volumes. As such, dynamic markings are used more as indicators of how loud a band should play, with further discretion available to the players. With this in mind, dynamic direction becomes considerably more important.

Once upon a time it was the norm for big bands to make the music their own, crescendoing and diminuendoing through lines when nothing was marked. However, these days the average player is much more likely to only play the dynamics marked on the chart. As a result, we need to include more dynamic direction throughout our arrangements. If you have a section that is marked at mezzopiano and then the next section is at forte, there will likely be some sort of build that takes place. Work out where and mark it with a crescendo. If you want it to be sudden, then you’ll also need to mark that just in case you have a musician who adds their own build.

Long notes also have a dynamic direction with very few in the big band tradition being unaffected. For example, in the Basie tradition the majority of long notes are given a fortepiano crescendo to help add movement to the duration of the note. You don’t have to add dynamics to every long note, but they are worth thinking about as they can add more interest to a line.

Phrase Markings & Articulations

When you look at a melody it can be hard to decipher which notes are more important than others. Furthermore, if the line is filled with a string of quavers/eighth notes, having them all played equally can feel somewhat mundane and uninteresting. To avoid this from happening we can use phrase markings and articulations to help add contour to a melody and show musicians which notes to bring out. Additionally, it can help avoid multiple interpretations at the same time, something which makes even the best section feel sloppy.

Back in 2022, I was very fortunate to produce a concert of excerpts from Duke Ellington’s three sacred concerts with an all-star band in Melbourne. Due to time constraints I sourced transcriptions for most of the music from another arranger as the original material was unavailable. Unfortunately, when I opened up the PDFs of the music I realized that there was almost no articulations or phrase markings on the score and parts.

As we only had one main rehearsal in the lead up to the performance, I had to go through close to two hours worth of music and mark all of the appropriate information from the original recordings. I then had to spend 20-30 minutes at the start of the rehearsal going through all of the edits for the musicians to pencil in their parts. Even though it had taken me hours of work, by doing so, I was able to guarantee that the musicians would be unified in their interpretations and ultimately save precious rehearsal time. In the end, the performance went off with a bang and there were very few issues when it came to mismatching articulations and phrases.

I mention this story because if I hadn't noticed the issue, it is quite likely that I would have wasted close to $50,000 for an unpolished big band recording. Most of the time the risk isn’t as high but in every case it can be completely avoidable if articulations and phrase markings are used. In a post Louis Armstrong world, the established norm in jazz is to interpret a line as legato unless stated otherwise. However, not all lines should be interpreted this way, nor does every musician default to legato, and what happens if you are playing a different style altogether? You can see how quite quickly a simple melody line can be understood differently and lead to a mixture of interpretations depending on the given context.

Starting off with articulations, the general rule I was told by Rich DeRosa was that every crotchet/quarter note must have an articulation. There are four options: short (staccato), long (tenuto), accented long (accent), accented short (marcato). There is some wiggle room with how each can be interpreted but by picking one you lower the chances of issues on the bandstand. If you are unsure which one to choose, try singing through the melody and swapping out articulations until you find one you like. Alternatively, you can always ask another musician or look at how other bands have played similar figures for inspiration.

Phrase markings on the other hand help musicians identify how different notes are grouped. If you have a long string of notes, phrase markings help indicate which ones may be more important as well as where potential breaths should be taken. In some instances, such as Bebop and post Bebop swing styles, they can be used to indicate a more accurate representation of the tonguing and ghost notes that takes place over fast lines.

When used together, articulations and phrase markings provide an accurate insight into how a composer wants a line to be interpreted. Sometimes you may want a player to be able to interpret a line freely and you’ll give them less information. However, if there are more than one musician on a given line and you want them to sound unified, you should include the same phrase markings and articulations in each part.

Enharmonics/Accidentals

I think it’s safe to say that everyone would prefer to not read accidentals if possible, especially double sharps and double flats. They add a layer of complexity into reading music which can trip up even the most seasoned professionals. That’s why it is our job as arrangers to look over the music we write and make sure every accidental makes sense.

On the surface level this means looking through every single instrument’s part and checking to see if they have any unnecessary enharmonics. Such as changing Cb to B, B# to C, E# to F, and Fb to E. There will be some contexts where a given key signature may justify such a note so take it on a case by case basis. We also need to go a bit deeper and look through individual lines and check that the accidentals make the most sense. A general rule is when ascending you favor sharps and when descending you favor flats. However, certain situations require a little more nuance.

In general the best approach to checking if you’ve used an optimal accidental is to look at both the chord symbol and resolution point of a melody. For example, if you were arpeggiating through a D7b9 chord, it would make sense to use an Eb and F# in close proximity regardless of the direction of the line. However, if in the next bar that Eb was resolving into an E, it may make more sense to write it as a D# as it is acting as a leading tone. Every situation will be different and as long as you’re taking the time to look over each line you will likely find the best choice for the musician.

Beaming & The Invisible Bar Line

If you’ve come through any music theory class you’ve likely come across the invisible bar line. I was introduced to the concept back in year 11 but it was never explained to me in a logical way, at least in relation to reading music. The general idea is that in the middle of a given bar there is an invisible bar line where if you were to cross it with any rhythms you’d have to treat it like any normal bar line. For example, in a standard 4/4 bar if you were to place a dotted crotchet/quarter note on the and-of-2, you’d have to break the note down into some kind of tied rhythm as it crosses the invisible bar line.

By having the invisible bar line it helps simplify rhythms and thus makes the music easier to read. However, this is not always the case. For example, you don’t need to break down a semibreve/whole note into two tied minims/half notes, nor do you have to break down a dotted minim/half note. Where it starts to get problematic is when you have notes longer than two beats that start and/or finish on quaver/eighth note subdivisions. Each of these has to be treated with care and sometimes you’ll find the invisible bar line makes it look more complicated. Use your best judgement and don’t feel like you have to strictly enforce the rule. The goal is always to find the easiest option to read.

Another way the invisible bar line can be helpful is by avoiding beaming over the line. This breaks up rhythms into smaller groupings which are far easier to read and simplifies the music. Once you get smaller subdivisions such as semiquavers/sixteenth notes, you may need to think in the opposite direction and beam over rests so that it is easier to identify exactly which beat a note is landing on. You’d still respect the invisible bar line but don’t be afraid to beam notes over rests if it makes the music easier to read.

Score Formatting

Having established a number of general formatting areas, it’s time to shift gears and look at scores and parts. In both cases the same rule applies: make it look as clean as possible. Both share some similarities, such as placement of rehearsal figures and double bar lines, but they also have many differences too. When we look at scores we have to put ourselves in the mind of the conductor. What is the most important information for them to see? What isn’t necessary? That way all of our choices will be guided by practical reasons and most likely be helpful regardless of how much we know about engraving.

Orientation, Page Size & Bars Per Page

In a world where we can guarantee that our music will always be printed on the same sized page, the perfect layout for a big band score is landscape on A3 or Tabloid sized paper. It has enough space for 17 or 18 instruments and coupled with somewhere between 8-16 bars per page and the notation is big enough for most people to read off of a music stand. However, there are so many cases of directors printing out scores formatted this way on paper much smaller, such as A4 and Letter, and if you’ve ever been someone who has done this you’ll know that to read the music you have to have a microscope. For this reason, I’ve provided two formatting options so that depending on the situation you’ll know how to approach it.

The ideal situation is a little bit easier to start with as there is far more space to work with on larger paper sizes. As we are dealing with up to 18 instruments, landscape orientation paired with A3 or Tabloid paper size gives a considerable amount of room for each of the instruments to be spread out evenly. It’s natural to want to cram a lot of bars per page with a large page size, however it’s important to remember that with each additional bar there is considerably more information being presented. If each instrument was playing, then one extra bar can be equivalent to 18 new lines to look at. As such, the optimal number of 4/4 bars is 8 for this page size. Sometimes you can go use more or less, with the blues offering a great example for why you might want to use 12 bars a page. Later on when we discuss rehearsal figures, this will also impact where page breaks take place and may affect the number of bars per page.

If you are unable to print scores on larger sizes of paper, or if you are unsure how your clients may print a score, then you may want to look at the portrait orientation. The problem with smaller sizes of paper is that it becomes difficult to space the instruments out adequately. By flipping the orientation from landscape to portrait we sacrifice the number of bars per page for larger staves and more space between instruments. It is in no way ideal, but it does stop conductors from squinting at scores or holding them directly in front of their face in order to read the notes. In some cases we may still be able to have 8 bars per page when most of the instruments are resting, but the majority of time you’ll be lucky to get as many as 6. In general I’d suggest 4 bars per page for full band sections.

Rehearsal Figures, Bar Numbers & Double Bar Lines

Together, rehearsal figures and bar numbers are essential for a productive rehearsal. Both of them indicate precise musical moments and help musicians communicate with one another when changes need to be made. When it comes to the score, bar numbers should be every single bar. Let me say that again with emphasis. Every. Single. Bar.

I learnt this the hard way at the recording of my first big band album. At some point during the session, one of the musicians asked me a question to do with their part. They mentioned the specific bar number and because I didn’t have any bar numbers marked on my score, it took me minutes to find the phrase they were asking about. Something which could have taken seconds otherwise. That night before the second day of recording, I took the scores home with me and manually pencilled in all of the bar numbers to avoid any more issues.

It doesn’t matter where you want to locate the bar numbers, they can be at the top, somewhere in the middle, or at the bottom. I prefer the latter, but as long as they are clear and readable that is all that matters.

Rehearsal figures on the other hand help locate larger sections of a piece. There is some debate as to whether you should use letters versus specific bar numbers but I personally prefer letters for one reason. In a live situation if something happens and you need to rally a band to a section, it is far easier to communicate a single letter than any sort of bar number. Moreover, you can often make the shape of certain letters with your hands which means you don’t need to verbally communicate in delicate moments. For rehearsal purposes, both letters or numbers work but I figure as I include bar numbers every bar already, having letters for rehearsal figures allows both options to be used if needed.

When it comes to formatting rehearsal figures, one thing I picked up from Hollywood orchestrator Tim Davies, who often formats music for the top studio musicians in LA, is that rehearsal figures should always be on the left hand side of a page while double bar lines should always be on the right. By doing so, it keeps the page very neat and you always know the start of a section will be on the left of a given page and not somewhere in the middle. As I previously mentioned, this can lead to some odd bar groupings at times but even so the score will look a considerable amount more tidy than making sure each page has a strict number of bars. If you are wondering when you might want to add a rehearsal figure or double bar line to the music, rehearsal figures generally go at the start of sections whereas double bar lines go at the end.

Score Order & Grouping Bar Lines

With so many instruments on a big band score we need to make sure that we group similar instruments together and follow standard score conventions. Following on from classical score rules, a big band score has the woodwinds on top, followed by the brass, and then the rhythm section. More specifically, within the woodwinds it goes Alto 1, Alto 2, Tenor 1, Tenor 2, and Bari, in the brass you have Trumpet 1-4 then Trombone 1-3 and Bass Trombone, and for the rhythm section it goes Guitar, Piano, Bass, and Drums.

Often music notation software defaults to grouping all of the instruments together with bar lines being stretched from Alto 1 all the way to the Drums. However, this leads to a very confusing score layout where it is quite difficult to pinpoint a specific instrument quickly. Instead, each section should be grouped individually with a gap in the bar line between the last instrument of a section and the first instrument of the next. For example, all of the saxes should have grouped bar lines, then there should be a break, then the trumpets have shared barlines, then another break followed by the trombones grouped together. When it gets to the rhythm section, as each instrument is unique, they should all have their own bar lines and not be grouped together.

Transposed VS Concert

In almost all situations the default for big band scores is to use transposed notation where every instrument is written with the appropriate transposition instead of in concert pitch. The main reason behind this is because it more accurately reflects the parts each player has in front of them. It is quite common in a rehearsal for players to seek clarification about certain notes, and it is quicker to locate notes from transposing instruments on a transposed score. Sometimes the conductor may need to transpose a given note back to concert pitch to understand how it relates to a chord symbol. In these instances, it is still better to do the mental transposition after locating the note then before.

If you were to take the rehearsal and performance element out of the picture, then concert pitch scores become a lot more useful. Personally, when I’m analyzing scores I prefer concert pitch as I can more easily see how notes relate to one another. Perhaps that means I need to work on my sight transposition more, but either way concert pitch scores are considerably more practical from an analytical standpoint.

Neat & Tidy

Regardless of which areas you decide to focus on when formatting a score, the number one thing to remind yourself of is to make it look neat and tidy while still being practical. Each of the elements discussed so far help achieve that in a different way but sometimes by utilizing all of the methods you may overcrowd the score. In such cases, you may have text, dynamics, bar numbers, or any number of details colliding with another.

Some common clutter culprits (try saying that ten times in a row) include:

Using staff text instead of system text, where you have the same information copied across on each instrumental line instead of one universal text on the top line

Too many ledger lines which cause dynamics and text to merge into the notation

Writing too much text in a given part

Having too many bars per page which can increase the note density on a page

Chord symbols hitting bar lines

If this is happening then you need to either reduce your stave size to create more room or manually shift the problematic information around yourself. In rare cases you may not be able to find a solution, in which case simply try to make the score look as good as possible even with the collision.

Part Formatting

Fortunately, when it comes to formatting parts there is a large crossover with many of the techniques we have just looked at with score engraving. At the core of the process is exactly the same mentality where we think about the player who is going to play the chart and try to create the simplest and clearest piece of music which best conveys our ideas. There are also a few unique elements which differ to how we format scores such as dealing with page turns and multi-bar rests. So let’s jump into it!

Page Size, Orientation, Bars Per System & Systems Per Page

Unlike scores which have two different viable options, when it comes to parts we really only format them in one way: portrait and on A4 or Letter sized paper. Once upon a time parts came on larger pieces of paper, but these days those options are far pricier and often inaccessible compared to the cheap and commonly found A4 and Letter sized paper. And when we look at the orientation, regardless of whether you are in a pro situation, a school band, or any other musical situation, you’ll find that portrait orientation reigns supreme across the published music notation world.

With this as our formatting foundation, we can now start to look at how many bars we can cleanly fit onto a page. In most cases the average advice is to have four 4/4 bars per line, and anywhere between 8-12 lines per page. However, if you’ve ever written music you’ll know that it’s never as clean as that. Depending on rests, section lengths, and the density of rhythms in a part you can make anywhere from 2 bars to 12 look good per line. There are also times where you can cram more lines into a page when needed but they vary from case to case. Every part will require a unique touch, so use your best judgement and try to be consistent where possible.

Rehearsal Figures, Bar Numbers & Double Bar Lines

Just like we mentioned with score formatting, in the parts you want to keep rehearsal figures to the left of the page and double bar lines to the right. It helps a page look clean and whenever a rehearsal figure is called, musicians know that they just have to look down the left hand side of the page to locate it. Of course you can break from this at times, but if you do so just make sure the end result looks cleaner.

Shifting over to bar numbers, unlike scores it is less important that we have bar numbers every single bar. I personally prefer having them at each bar where possible for practical reasons such as when a musician gets lost mid section and needs help from the conductor to get back on track. For some cases, such as vocals which often have lyrics that can collide with the bar numbers, I’ll opt for bar numbers every system instead. There is no universal rule as to whether bar numbers should be below or above a given bar, just go with what you like the best. Personally, I go below the staff, directly under the bar line as they are far less likely to get in the way of text like chord symbols and rehearsal markings.

Multi-Bar Rests

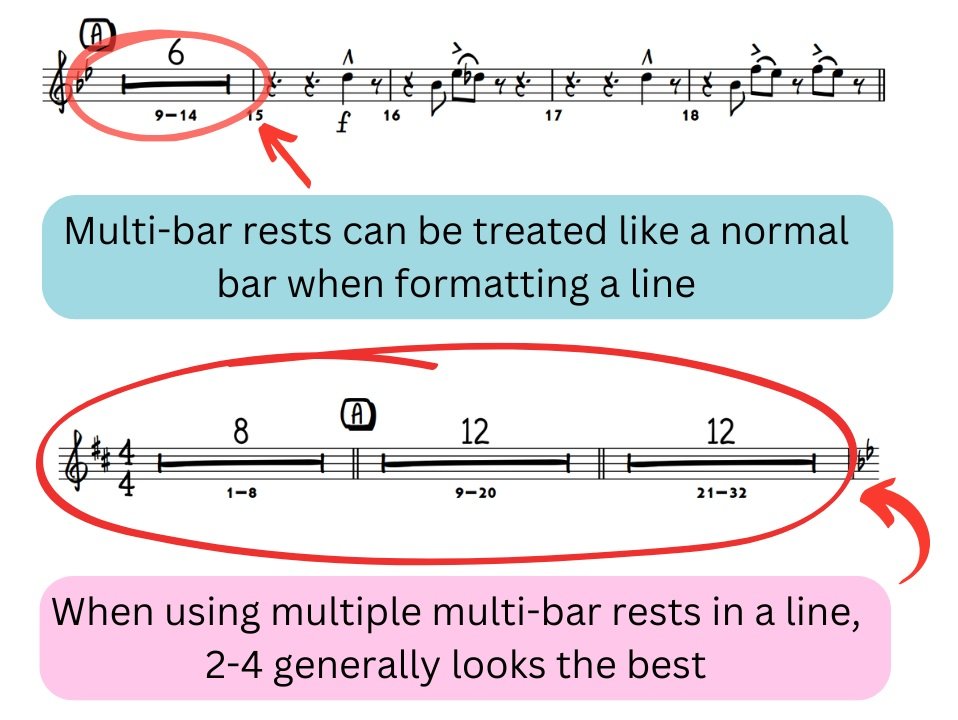

For the most part, most music notation software will automatically convert any groups of rests into multi-bar rests. However, in some rare instances there have been charts I’ve seen which do not do this and instead have dozens of rests back to back. When this happens it not only extends the number of pages for a given part but is also a pain for any musician to read. On the positive side, when used properly, multi-bar rests can save a considerable amount of room.

In a situation where you have a multi-bar rest in the middle of a section, you can treat it as an individual bar for formatting purposes. However, as soon as you have a number of multi-bar rests back-to-back, generally you want to limit it to 2-4 per line. Use your best judgement and try not to squish too many together.

Page Turns

We’ve all been there, in the middle of a phrase trying to somehow free up a hand to make a horribly placed page turn. Personally, as a bassist I’ve seen this problem hundreds of times across my career, and each time I get just as annoyed. One Christmas in particular, I was asked to play bass for a local big band. I happily accepted only to find out we were going to try and fit a 20 piece band alongside 5 vocalists onto a tiny stage. Having no more than a square foot of room to somehow fit my upright, bass guitar, music stand, and myself, I thought I had solved the biggest issue of the night once I had finally navigated the cramped space. Only to realize when the band leader dropped a 12 page chart with no taped pages and a 300 bpm tempo marking that the night was only just getting started.

For those unaware, jazz bass parts often play throughout an entire piece with no rests and this chart was no different. Staring down at a 12 page behemoth at that tempo, I knew I would have to compromise playing four or so bars every time I had to make a page turn. In other settings I would usually try to get more stands, but due to the limited space on stage, I was going to have to make do with the one I had. Let’s just say it didn’t go well. Sheets of music went flying off the stand as I tried to move my hands fast enough to page turn without breaking the groove. Somehow I found myself at the end of the chart without too many bruises but due to some terrible page turns I had looked like a considerably worse player and felt embarrassed in front of the audience.

Up until now the priority when formatting a chart has always been to make a piece of music look clean. However, there is one big exception to this rule and that is to accommodate page turns. I think I can speak for all musicians when I say that I’d prefer to have a somewhat cramped page of music if it meant that the page turns were in the most optimal spot. This might mean that rehearsal figures aren’t always on the left side of the page, or perhaps you’ve had to put more than four bars per line and somehow squeezed 12-16 lines per page.

In order to locate a good page turn we must first decide how many pages we want open at a given time. The typical music stand can allow for three to be open at once, but if you are formatting for a booklet you will be only dealing with two. That means that for the typical piece of music you should be trying to format page turns between pages 3 and 4, and then every two pages after that (5 and 6, 7 and 8 etc). With this in mind we have to then look at where the music might naturally allow for a page turn on page 3. Sometimes it might happen at the end of the page and perfectly line up, or it may be somewhere halfway up the page where a multi-bar rest takes place. The important thing to consider is how much time the page turn may take given the tempo of the piece and try to find the best possible place in the music for that to take place.

In a situation where no area presents itself for a page turn, you need to start thinking about the instrument you are formatting for and any characteristics which may help it in the situation. For example, it is easier for a trumpet player to make a page turn while playing as they only need one hand to play. Whereas a bass or guitar can play an open string with only one hand while using the other to change pages. In the worst case scenario, just make sure the page turn is not in the middle of a phrase.

Neat & Tidy V2

Just like scores, there is a high chance for collisions on formatted parts. Unfortunately, if you’re dealing with a lot of information in a chart, there’s no way to avoid it happening. Fortunately the solution is the same as what we covered earlier and the best way of fixing the issue is to reduce the staff size or manually shift certain details. If you still can’t seem to make it work, a unique solution for parts is that you can have less lines per page to help stretch out the distance between systems. And if that doesn’t solve the problem, just try your best to make it look as presentable as possible even with the collisions.

Taping & Binding

Now that you have a wonderfully formatted chart you are pretty much finished. If you are sending it off to a client there’s nothing more to do, however if you plan on printing it out yourself and bringing it to a local rehearsal you may want to consider taping the parts and getting the score bound. The latter either requires you to buy a binding machine and do it yourself, or the easier option is to go to a print shop and ask for them to bind it like a booklet.

Taping charts takes a little more time and you are unlikely to find someone you can pay to do it for you. If you’re lucky you might be able to rope in a friend or two, or have a significant other that is willing to donate an evening of their time to help you. Unfortunately, taping pages together is timely and is maybe the least fun part of the entire arranging process. But like formatting, it makes the experience of reading music that much better. The two main reasons we tape charts are so that instrumental parts are contained which makes it much harder to lose individual pages, and that it helps with page turns.

After having taped tens of thousands of parts myself, there is a certain method which seems to lead to the best results. First you want to make sure you use painters tape or masking tape as it has more strength than other options but is still able to be removed and cut easily. Then you want to line up the first two pages and tape the full length of the page. Some people will say to then cut off the tabs on either side of the page but I simply fold them over and stick them onto the other side of the page. From there, you alternate taping on the front and back for the coming pages. For example, between page one and two you tape the front, then between two and three you tape the back and so forth. By doing so you create a somewhat accordion effect which helps the pages fold more naturally.

It may feel like an inconvenience for you as an arranger, but I can guarantee that everyone in the band will be grateful for the time you put in. Not once have I ever heard someone complain about a taped chart but there have been countless times I’ve heard complaints about loose parts.

The Takeaway

If you want your music to be taken seriously and interpreted correctly, formatting is a necessary component of the arranging process. As you’ve seen on this page, there are a number of factors to consider when you format a chart and at the beginning it may feel difficult to keep track of them all. Try your best and as long as your goal is to keep improving, you’ll find your skills getting better every time you sit down and format a chart.

The methods I’ve focused on here come from over a decade of trial and error where I’ve consistently asked musicians for their input and adapted my approach. I didn’t learn how to format from one particular book or teacher, and my process is constantly evolving. I don’t want you to come away from this page thinking that these are fixed rules which have to be followed at all costs. Instead, try to take a looser approach which is built around making sure that your charts look good, are easy to interpret, and are practical for the musicians which play them. If you follow those three goals, you’ll know when to break from the rules and you’ll ultimately end up with fantastic looking charts!