The Key To Writing Shouts, Solis

& Other Common Sections

One of the most exciting parts of writing a big band arrangement is being able to organize all of the techniques you’ve acquired into one cohesive chart. However, like many aspects of writing, that can feel pretty overwhelming trying to think about all of the possible ways to divide up a chart. To make things easier, a great method is to look at what other arrangers have used and become familiar with the different section types available to you. You can then think of these sections as a way of breaking an arrangement into bite size chunks which can be worked on one at a time.

Although there are countless different types of sections at our disposal, on this page I’m going to restrict my list to only the most common, and thus what I think are the most essential to the art of big band arranging. An arrangement doesn’t need to feature all of the sections covered, it may only feature one, and in some instances maybe none at all. The main point is that you are aware of them and understand how they operate so that you can capture that sound in your own writing if you desire. Once you feel comfortable with each of these techniques, if you are looking for more inspiration I would suggest borrowing ideas from other types of music. Just by looking at the classical world you’ll find dozens of unique options.

Solis

Out of all of the sections covered on this page, solis offer the best way of demonstrating both the prowess of the players in an ensemble as well as the sophistication of the writer. I can’t remember the first big band soli I fell in love with, but I do remember sometime around the age of 17 or 18 when I was introduced to the Jerry Hey Horn section.

Being primarily a bassist, my record collection at the time was stacked heavily toward musicians like Victor Wooten, Marcus Miller, and Jaco Pastorius. However, by attending a school with a large music program, many of my friends played different instruments and listened to a wide range of albums. One day, my mate Jed (a trumpeter) came to school saying that I had to check out this YouTube video of the Jerry Hey horn section, stating that I wouldn’t believe how tight they were. Sometime that day I found the video he was talking about and was blown away. The section was playing virtuosic lines that very much seemed impossible to my teenage self whose only idea of good horn playing came from an amateur high school big band. It’s safe to say that my idea of what horns could do changed forever.

A few months later Gordon Goodwin’s Big Phat Band came to Australia for the first time. At the time I didn’t realize that these were some of LAs top studio players, many of whom had done work for Jerry Hey. However, when I saw them live I realized that what I heard on that video months earlier was not just studio magic but completely achievable in a live setting. It didn’t matter which instrument, that single performance demonstrated that every section of a big band could play virtuosic lines and when they did it was not only extremely impressive from an audience standpoint but also a way of adding interest and complexity into a chart.

Since then there have been a few other standout moments where a soli has knocked me to the ground. The most recent being in 2019 when I heard the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra live in Melbourne play Braggin’ In Brass by Duke Ellington. I never knew trombones could be so tight when playing an intricate melody that was hocketted between three horns. Simply jawdropping.

These are only a few examples of how I’ve felt when hearing a soli and I include them because I want to convey just how mesmerizing it can be to hear great musicians featured on captivating melodies. As writers, solis offer us the ability to stretch our fingers and really show off our writing chops. That doesn’t mean at the expense of musicality, it just means that in the jazz tradition they have been established as moments of virtuosity and thus allow us a bit more freedom with our lines. A great soli combines interesting harmony through passing chords and voicings, while also highlighting lines which can feel almost improvised. Finding the right balance is difficult but when you do you can create magical musical moments.

Before we jump into the nitty gritty, a lot of this page builds off past resources including those which cover passing chords, extensions and alterations, 2-5 horn voicings, big band voicings, as well as how to compose melodies. I would highly recommend checking them out before reading ahead so that you are familiar with all of the terminology and techniques discussed.

How To Write A Soli

The key to any great soli is creating a great lead line. What exactly constitutes a great melody though is up to your personal tastes. However a great place to start with soli writing is trying to emulate an improvised solo. Generally improvised solos include a higher density of notes and may cover more of the interesting chord tones where possible. What this means is that you will likely use more quavers/eighth notes and triplets, as well as highlight more extensions and alterations where possible. There’s also room to add different embellishments like scoops and turns too.

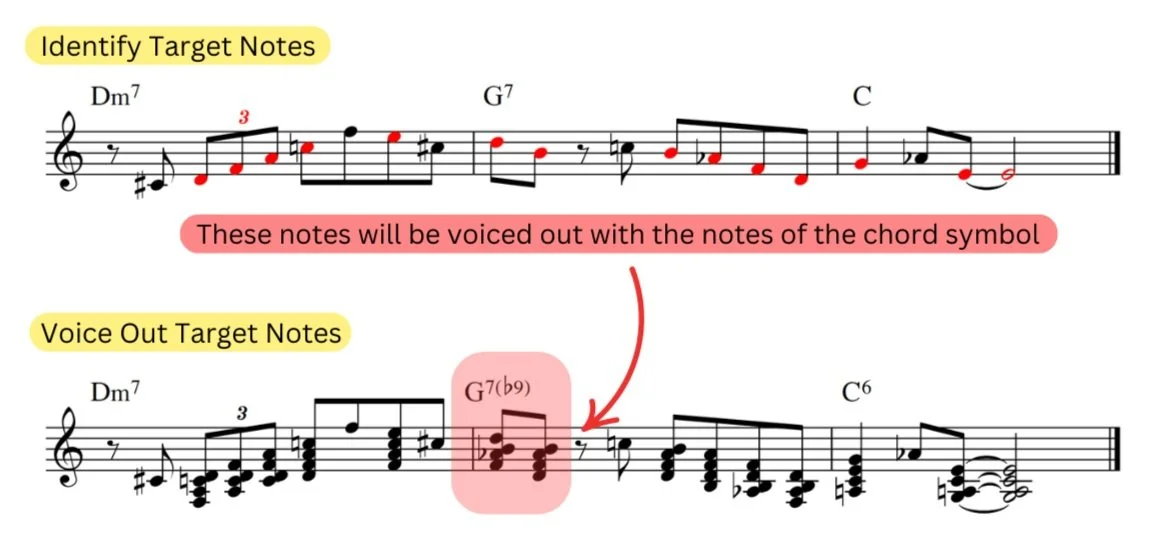

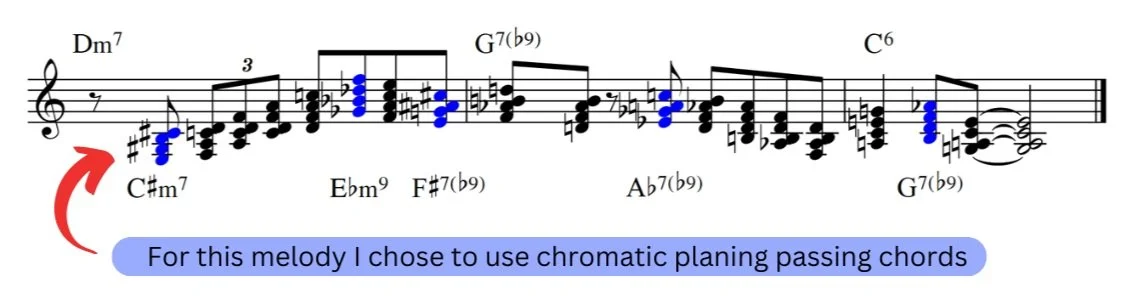

After establishing a melody line you need to decide on how much harmonization you want to use. In some cases it will be better to harmonize the whole section and in others you may want to use more unison/octaves. If going down the harmonization route, the key is to work backwards from target notes. In this case, target notes are melody notes which will be voiced out with the notes of the accompanying chord symbol. For example, if a melody line is arpeggiating Dm7, then each of those chord tones would be voiced out with the notes of Dm7. As to what voicing you want to go with, there are a lot of options at your disposal but the most common will be some sort of closed voicing.

Once the target notes have been voiced out, you can then allocate various passing chord techniques to the remaining non-chord tones. This will add a bit of harmonic flex to the line and help create interesting inner lines. Where possible try to avoid repeated notes and leaps larger than the melody in the inner voices. Otherwise you may create less than ideal parts and take away from the lead line.

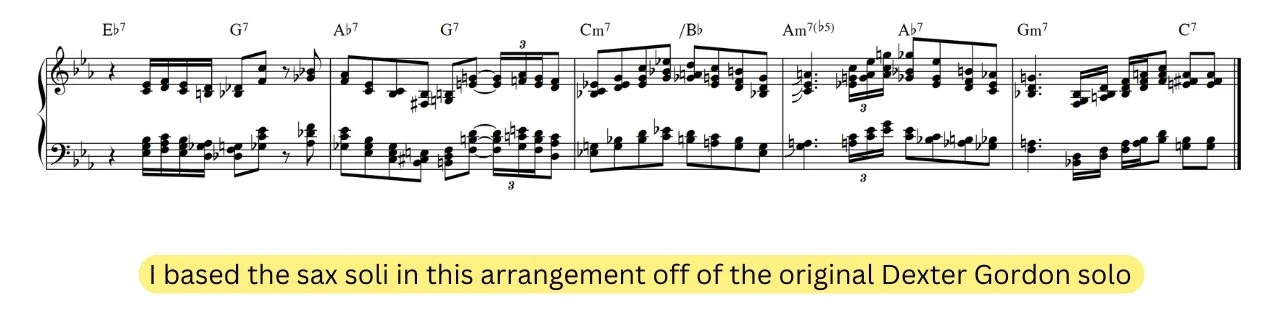

A great place to start writing solis is to take preexisting improvised solos of your favorite artists and try to harmonize them. That way you don’t have to worry about crafting a great melody line and can focus purely on the harmonization. You’ll also get the added benefit of seeing how improvised lines navigate chord progressions which you may be able to emulate in your own writing later. Plus, those in the know will consider your soli a homage to the jazz tradition.

Driftin’

Arr. Toshi Clinch

With the basics of creating a soli covered, you should be aware that there are some differences between each section of a big band. All of the instruments have unique characteristics, some which can both help and hinder certain soli approaches. Be aware that what works for one section may not work for another.

Sax Solis

The sax section might be the quintessential group of instruments to write a soli for. They definitely do the heavy lifting when it comes to big band solis and are the favored section of many arrangers. So much so that when you learn soli writing in university they typically only cover how to write for the saxes. That’s because they can take almost anything you throw at them. You can harmonize them with 5 part voicings, they naturally balance well because of the mixture of alto, tenor, and bari, and it is more common for a sax player to be able to execute fast passages across the entire horn. Well at least students get to that level much quicker than their brass counterparts.

The approach I just unpacked of writing a lead line and harmonizing it will work perfectly for the saxes. In fact, that is exactly how I learnt how to write my first couple of solis. The only addition I’ll make is that you can use a number of different voicing options, all of which are covered in the big band voicings resource I’ve written. If you’re just starting out, I’d recommend getting comfortable writing solis for the saxes before attempting any of the other sections. They are much more forgiving and it will be the perfect place to build up your confidence.

In A Mellow Tone

Arr. Frank Foster

Trumpet Solis

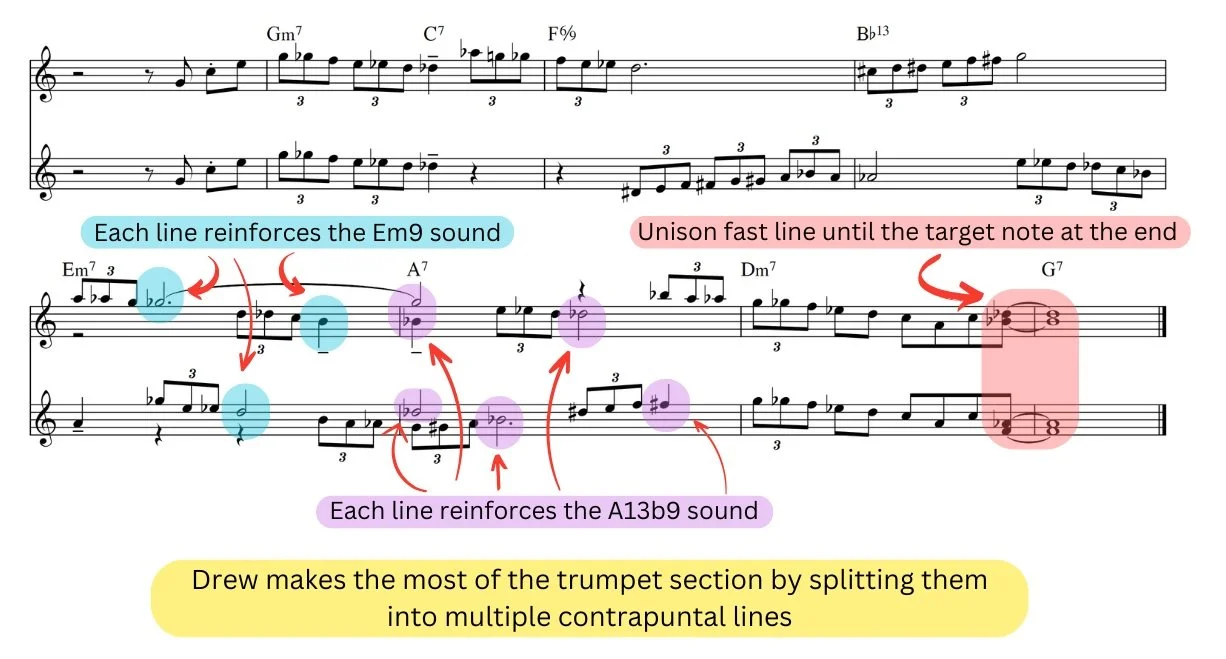

Moving over to trumpet solis, they are a completely different beast to the saxes. Out of the three horn sections, they are represented the least in the soli department. There are still a couple of them out there in the wild, and when you find a good one they stand out more than any other section, but they are few and far between. Why is this the case? Well it’s much harder to harmonize them effectively and as a result so much easier to make them sound bad.

So how might one handle a trumpet section? Well instead of coming in expecting to harmonize every note like a sax section, you should take the opposite approach where unison is going to be your best friend. Rely more heavily on writing fantastic lead lines that stand out on their own. Trumpets are not known to make huge leaps regularly, and when they do it can be taxing on the players. Instead, try to form lines which utilize stepwise motion with smaller leaps where needed. Be aware that as you get into the higher register, leaps can have a greater impact on a player’s chops.

Although trumpets can play fast, and the best players can equal the technical abilities of a sax section, it is not as common for a trumpet section to be so dexterous. However, you can create interest in other ways such as by adding shakes, doits, falls, growls, and glisses. Each of which will add unique elements which are just as impressive and help lean into the unique timbre of the instrument.

Once you have that as a foundation you can look at harmony as being a tool to highlight certain target notes and bring more emphasis and punch. But before you jump in and write out a full 4 note voicing, if the lines you are writing are fast and require large jumps for the inner voices to go from unison to harmony, perhaps look at simpler voicings that land on interesting chord tones more than full voicings. That translates to using triadic voicings in most situations.

Sometimes it is unreasonable to write harmony in this way, in which case we need to look at other approaches to add interest to the inner parts. One option is contrapuntal writing where you might create one or two counterlines that move alongside the melody either homophonically or polyphonically. The interest comes from the differences in motion between the lines as well as the unique chord tones which each line may land on. This is definitely the hardest approach to writing a soli but can be very fruitful if done right.

The Song Is You

Arr. Drew Zaremba

Trombone Solis

Somewhere between the approach for the trumpets and the saxes lands the trombones. Due to their slides they don’t usually play lines quite as fast as the saxes (although some pro players can) but they can play a bit more harmony than the trumpets. There’s no hard rules when it comes to what works the best for trombones but in my own journey I’ve found it’s best to mix harmony and unison lines, where you might prioritize harmony on slower moving rhythms and unison on faster lines. As the instrument has a lower frequency than the trumpets, too many thick voicings can bog them down especially on speedier passages.

Vesuvius

Toshi Clinch

Rhythm Solis

Moving over to the rhythm section, they too can be featured in soli passages, albeit uncommon. So much so I don’t actually have any specific examples where rhythm sections are featured in a soli isolated from the horns. However, I do have some approaches that may be valuable to you if you choose to incorporate a rhythm soli into your big band arrangement or perhaps are looking at incorporating a soli into a combo chart.

Due to the section being made up of four different instruments, my general recommendation is to use a lot of unison/octave voicings. As the rhythm section typically plays time and provides the foundational harmony of a piece, when you shift to playing a melodic line in all of the instruments it stands out immediately. There are ways of incorporating harmony in both the piano and guitar parts but they generally aren’t as impactful as the fact that all of the instruments are playing a melody line. The drums can also reinforce the rhythm of the soli instead of playing a time feel.

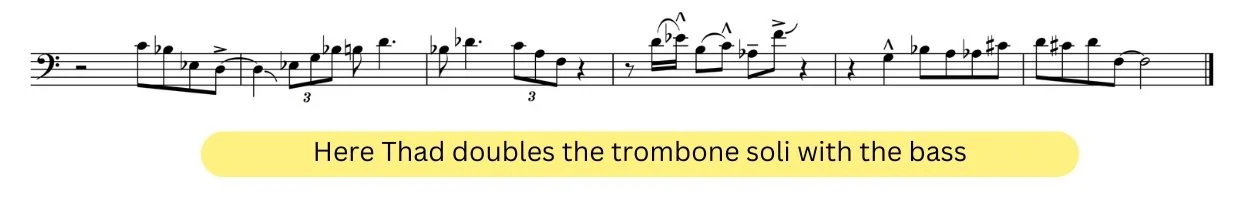

More commonly the rhythm section finds itself doubling solis alongside other sections. Sometimes the whole rhythm section is utilized and other times it can be a single instrument. For example, Thad Jones often would double trombone solis with the bass.

Tiptoe

Thad Jones

Tutti Solis

Sometimes instead of focusing on just one section, you can have the whole band play a soli. With the whole band playing the same line you get a lot more impact and power. However with that many horns playing intricate lines comes a responsibility on the arranger to not make the music feel too heavy. That’s why so many writers use minimal voicings during large tutti solis. For example, one of my all time favorite writers, Bill Holman, is known for his extensive use of unison/octaves. To the point where his big band arrangement of Just Friends is renowned for the use of unison/octaves for close to 200 continuous bars.

Just Friends

Arr. Bill Holman

The next step is to apply the same mindset as what we discussed with trumpet solis, where certain target notes are selected to feature full band voicings. This way you get a wonderful mixture of both smooth almost weightless lines, while getting moments where the band produces a big wall of sound. When utilizing this method, the full band voicings can make use of a number of shapes, all of which I’ve covered in my big band voicings resource.

Chill Or Be Chilled

Michael Giacchino

Sometimes you can get the rhythm section involved where they double the horns and other times they will keep playing time. The latter is more favored in older swing arrangements whereas more modern or non-swing styles seem to get the rhythm section more involved. In both cases, it is common for the drums to keep playing some kind of time.

The best thing about writing solis is that there is no right or wrong approach. You can be as creative as you like. Want to just feature the brass? Go ahead. Want to have guitar, flute and muted trumpet? Awesome. Want to have half of the soli be played by the saxes and then the second part by the trombones? Sounds like a great idea! Just make sure you focus on delivering great lead lines and the rest will take care of itself. And if you ever get stuck, try looking for inspiration from some of your favorite improvisers.

Shout Sections

When you think about big bands there is one section which reigns supreme: the shout section. For me it is the epitome of the craft, it takes all of the best elements of the big band format and cranks them to eleven. But most of all, it demonstrates the immense power a band can have when firing on all cylinders. There’s nothing quite like playing or directing a roaring shout section, something I’m lucky to have experienced a number of times.

As a young bassist, I often disregarded the horns in my school big band, choosing to focus on my own parts and making sure what I played felt good with the rhythm section. Rehearsals never were the most fun to begin with and at first I didn’t really understand what made a big band unique compared to the other ensembles I was in. Fortunately, one day changed that. At the time my school had some sort of affiliation with someone who MC’d corporate functions. As a result it meant that the senior band was invited to play dance sets at a number of high end events on a regular basis. Something I would later realize was not the norm for a high school band.

After a month or so being in the school big band, we got invited to one of these functions and were asked to play three hours of swing classics at the posh Melbourne Cricket Club at the MCG (the largest sporting stadium in Australia). Not too bad for my first “professional” gig and something I definitely bragged to all of my friends about for a matter of weeks afterwards. Regardless of the status of the event, something far more impactful took place somewhere in either the tail end of the second set or at the start of the third set.

You see, as a school band I think the first half of the music was most likely us warming up and shaking off whatever nerves we may have had. But sometime halfway through the band started to click in a way that only playing live will do. Once that happened my mind was taken away from the bass part and I started to hear the ensemble as a whole. I started to see how the music impacted the patrons and that more and more people were getting up to dance. I also began to get that special feeling of goosebumps you only get when the music really feels good. And you know what, the moment where that all started to happen was during a shout chorus.

I’d like to say I remember the exact chart but with time that detail has faded from my memory. Knowing the book that we played it was most likely a classic Basie number like Shiny Stockings or something a bit more generic like In The Mood or Little Brown Jug. Either way, the power of the shout section was engrained in my memory and it helped me fully realize how a big band can make you feel when everything is working together.

So how can we recreate that feeling in our own arrangements? Luckily writing shout sections may be one of the easier areas of big band writing as there are usually not that many moving parts and it only requires putting simplified melody lines in the upper register of the trumpets. However, you will need to understand how to voice for a full big band horn section, which as I mentioned earlier is a topic explored thoroughly in another resource.

How To Write A Shout

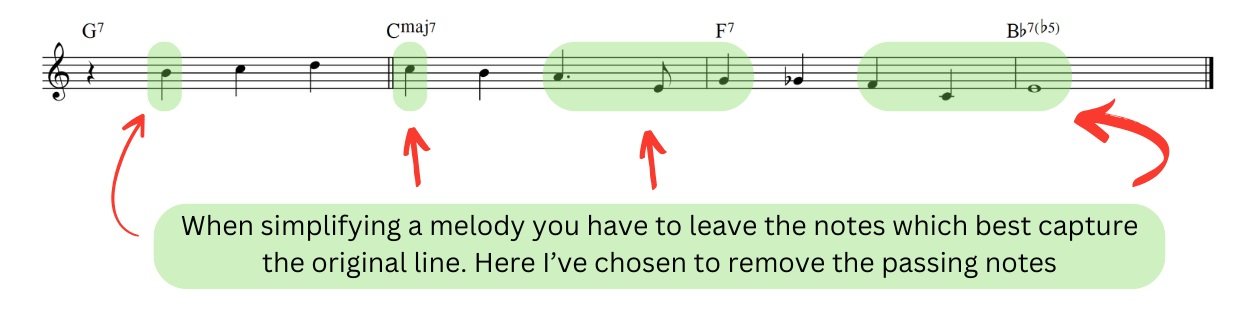

In a completely opposite fashion to solis, the main component to a shout section is hard hitting simplified rhythms. By stripping a melody down to its bare essentials you maintain the core feeling the melody gives but provide the necessary space to voice out up to 13 horns for a number of bars. Something which comes with a lot of weight and has to be dealt with appropriately to avoid feeling sluggish.

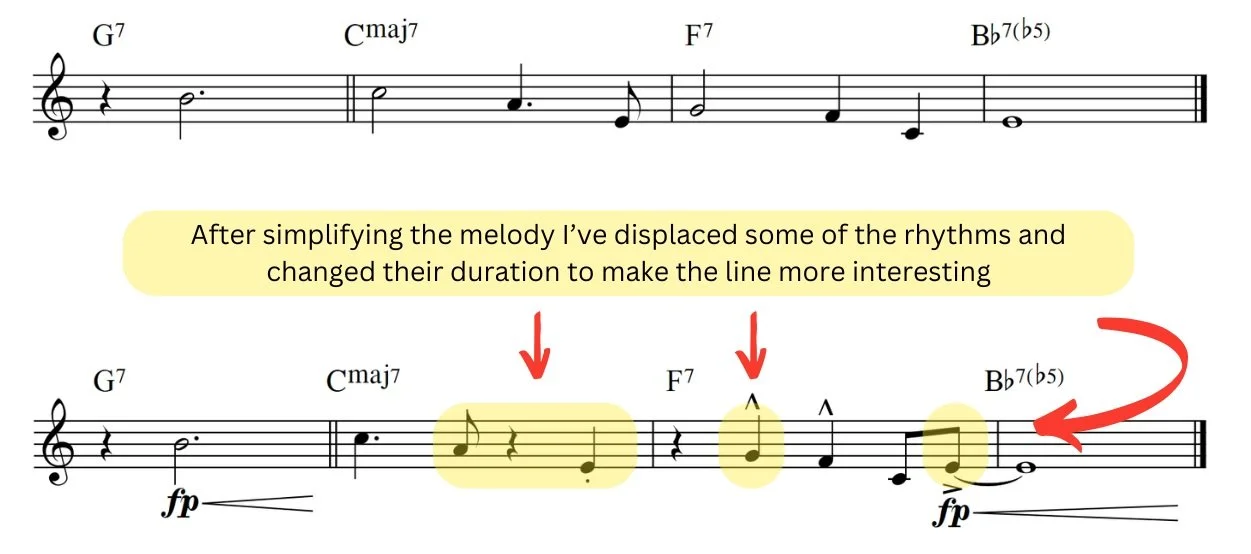

To simplify a melody you must first work out what are the core notes and/or rhythms you want to highlight. Sometimes if the melody is simple enough this could be entire phrases, whereas for melodies with more motion, it may just be key intervals and target notes. The best shout sections select notes which still give the essence of the original melody even when they are rhythmically displaced and other parts have been omitted.

Once you’ve located the important notes and/or rhythms you want to maintain, you can remove everything else, hopefully leaving somewhat of a blank canvas to work with. Now comes the fun part. The notes you want to bring more weight to, you can elongate and place on downbeats as well as pair them with iconic techniques like shakes or falls, and dynamics like fortepiano crescendos. You will still need some balance within a phrase and can’t just place everything on a downbeat so make sure to sprinkle in some offbeats and syncopation too.

Now that you’ve got your lead line, it’s time to plug in your voicings. For the most part you’ll want to make sure that there is some distribution of frequencies with not every instrument being in the upper register. The trumpets will do most of the heavy lifting at the top, while both the saxes and trombones have more room to spread throughout their entire range. Depending on the state of your melody, you may have some non-chord tones which will need to be assigned passing chords, otherwise this is the time to utilize the maximum number of chord tones for each chord symbol. With the horns spread out so much, you have the room to add all of the color tones and fundamental notes if you desire. Sometimes it’s not necessary but if you are looking for a big, fully realized 8 note chord, this is going to be the best opportunity to voice it out.

From there we shift our focus to the rhythm section. Other than dynamics, not much changes except for the drums. Instead of primarily playing time, in a shout section the drummer traditionally sets up each of the band figures with some kind of high energy fill. Almost to the point where it feels like a drum solo. Alongside the wall of horns, the drums adds an interactive element that brings a lot of excitement to the section and helps kick the horns into gear. In order for the drums to do this though, we must make sure we notate their part in a particular way. Sometimes this may be as simple as copying out the lead trumpet part, and in other cases it might look like slashes with key rhythms marked.

It’s also worth mentioning that as the horns get louder, the other instruments of the rhythm section won't be able to compete. The natural instinct will be to turn up an amplifier but this will actually ruin the balance of the band. Instead, embrace that the horns will dominate for a moment and then the rhythm section will start to be heard as the band comes out of the shout. A traditional option that sometimes gets used by drummers to help reinforce the acoustic bass in shout sections is to feather the bass. This is when they play four on the floor but where the beater only gently touches the bass drum. As the bass drum frequencies are similar to the upright bass, it gives the impression that bass is actually slightly louder and helps the instrument have more presence.

Hay Burner

Sammy Nestico

Divide & Conquer

Like every other aspect of big band writing there’s more we can do with a shout section than simply have the whole horn section play tutti. One of the most popular options coming out of the swing era was to split the horns into two sections, specifically the saxes and brass. The brass would continue the traditional role we just unpacked while the saxes were free to play some kind of counterline. Depending on the writer, the sax part could be quite sophisticated to the point where you could classify it as a soli. Sometimes the saxes may be assigned a riff, and other times they may have a more interactive part that plays off the space in the brass part.

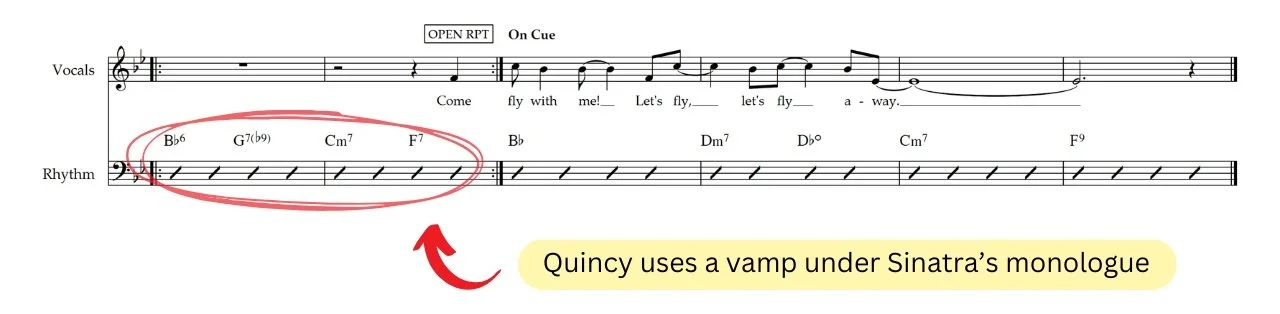

Come Fly With Me

Arr. Quincy Jones

Soft Shouts

Alongside the typical shout section is a somewhat ironically titled “soft” option which is a quieter alternative. The main components to writing a soft shout are the same as the loud version however the difference is that the lead line is placed somewhere in the middle to low register of the trumpets and not in the upper register. By pairing this with softer dynamics, you are able to increase the intensity of the section while still maintaining a level of excitement. Soft shouts also offer the chance for more dynamic variation as the lower register doesn’t force as much projection from the horns. This can give them a somewhat playful quality where you can bring out certain notes to surprise the audience.

In A Mellow Tone

Arr. Frank Foster

Other Common Sections

Shouts and solis are two of the most iconic sections found in big band writing. However they are not alone and there are many other staples that deserve mention. In fact, some arrangements don’t include shouts or solis at all, and are carried by a collection of other options, including: intros, outros, interludes, solo sections, breakdowns, vamps, and pedals. One of the most notable options that all arrangements include are melody sections, however as they are primarily built on the back of the melody, I’d suggest checking out the melody & countermelody resource where I look into that topic in more detail. For now though, let’s get stuck into the other options.

Breakdowns

Like the name suggests, breakdowns are when we reduce the band down to a minimal number of instruments, with many cases being a singular instrument like the drums. By dropping to only a few instruments, you can create a lot of contrast in an arrangement, especially if a breakdown is placed after a particularly dense section like a shout. In such cases it’s common for breakdowns to also be paired with a sudden drop in dynamics, however this is not always necessary.

I came across the technique somewhat organically due to a task my band director gave me some time back in high school. As the leader of the rhythm section at the time, he said I needed to devise a plan for the section to develop behind soloists. Not knowing anything about jazz or how professionals do this, I came up with different “gears” for the section to shift between. Safe to say it wasn’t what the director wanted but got my mind thinking more creatively about the limitations of the rhythm section.

That train of thought eventually led me to the discovery of breakdowns when I started running my own band. In order to add interest we would sometimes reduce down to just a soloist and the bass, or just the drums and slowly tier the other instruments over time. I’m sure I’d gotten the idea from a record I’d heard at the time but that’s long forgotten in my memory. As we started playing more gigs, we tried out the approach on real audiences and found that it led to higher engagement and more exciting solos. From then on it has been a trick I can always rely on as a bassist. However, as soon as I started writing I realized that it could cross over to arranging too. Whether I magically stumbled upon big band recordings which used breakdowns, or more likely just started hearing them in the music I was already interested in, by the time I reached my late teens they had made a mark on me and were in my regularly used techniques.

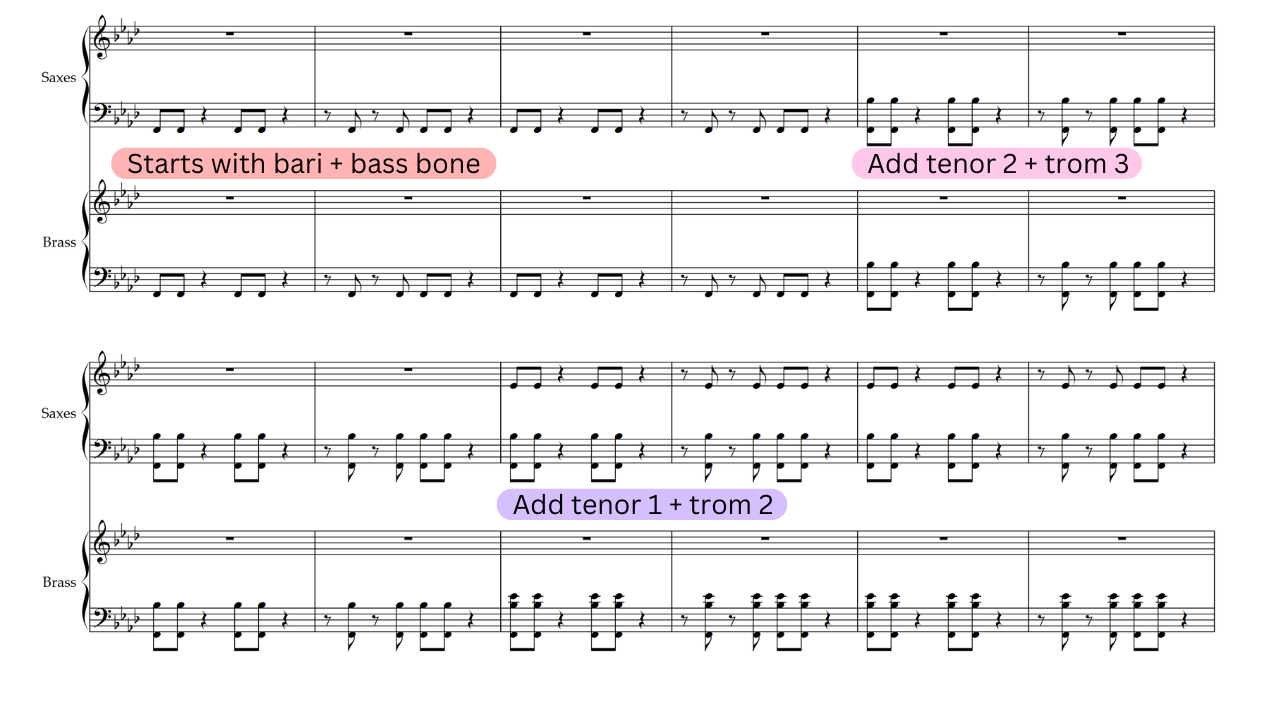

Crafting a breakdown is quite simple with the main component being to remove almost all of the instruments from playing. After reducing the instrumentation, you gradually introduce different layers which build off of one another. The most common example is having the drums start by playing a repetitive groove, then adding the rhythm section, followed by each of the three horn sections until eventually everyone is playing. When used in this way, a breakdown can be a great way to build into the following section and create motion within an arrangement. This is only one example though, and you can easily take the concept and introduce any instrument in any order.

Dance Mania

Tito Puente

Vamps

Unlike breakdowns which focus on a change in instrumentation, vamps are characterized by taking a small chord progression usually made up of 1-4 chords and repeating it for an almost endless amount of time. They are found in a number of places and are strong enough to carry an entire song when necessary. One of the more popular uses are as holding sections where you may need to wait for a soloist or some sort of cue before going onto the next section. However they also work as a wonderful harmonic contrast too when used as a standalone section alongside a common form structure like AABA.

I’m not too sure when I was introduced to the technique as a lot of the music I grew up listening to could easily be seen as being built off of one vamp or another. The approach litters pop music these days and can be heard almost everywhere. However, I do remember when I started to take vamps seriously in my arranging as a standalone technique.

In 2018 I had the chance to bring Grammy nominated composer/arranger Rich DeRosa to Australia for ten days of workshops, concerts, and educational seminars. It was truly a life changing experience for me in many ways and part of the trip was a concert featuring the music he had recently arranged for the WDR Big Band. The project was titled Ellington Rediscovered and was the creation of Rich alongside Dick Oatts and Garry Dial where they took unreleased sketches by Duke Ellington and reimagined them for big band. By producing the concert in Australia with my own band, I had the chance to both look through the expertly penned arrangements and also play bass in the ensemble.

Around the same time I was writing a large amount of music myself and kept running into the issue of how to help differentiate one solo section from another. So many times I would just use the one set of chords and have solo after solo play over the same section. Not that this was a bad approach, it just got to a point in my own writing where it felt stale and I wanted a way to help each improviser stand out. That’s when I noticed in Rich’s charts that he would often have soloists play over different types of sections, not just the standard changes associated with the melody. The one technique that really stood out to me was when he used a four bar vamp instead of a typical 32 bar form. Usually it took place a few minutes into the arrangement, after the form had already been established and someone had soloed over the original changes. As a result, when the new soloist began it felt fresh with a new set of chords and a much shorter cycle.

I immediately began using it in my own writing and luckily it was simple enough a technique that it worked immediately. It was also a great tool for some of the charts I was writing for high school bands where the students may not have the ability to solo over long complex forms. I could use all my fancy harmony tricks in the written sections and when it was time for the solo, revert to a shorter vamp with more user friendly options.

To add a vamp into your own arrangements, simply find a short set of chords you like and loop them. It’s that easy. As I mentioned earlier, this technique works for more than just solo sections and can be used as a holding pattern while you wait to cue someone in. Broadway musicals make use of it all the time when there are certain lines or choreography that needs to take place before the music continues.

Come Fly With Me

Arr. Quincy Jones

Pedal Points

The year was 2010 and I was in a rehearsal room playing a big band chart built on the blues. As a developing bassist, I hadn’t quite discovered the harmonic power my instrument held but that was all about to change. You see, in Australia there is one high school big band competition to rule them all. A national event held in Mt Gambier (a rural town 4-5 hours drive from the next closest major city) where hundreds of different schools gather for one weekend of big band music. It is a tremendous event that is on the calendar for nearly every high school jazz program in the country. As such, most ensembles spend months preparing for the event every year and my school was no different.

What this looked like in reality was playing the same three charts for a number of consecutive months. Something which felt like overkill at the time because my bass parts often didn’t require that much preparation. And you know what happens when you give a teenager ample amounts of time when they don’t feel stimulated, they goof off. What that looked like for me was trying out new ways to approach my walking lines, with no specific goal in mind other than to make them sound different. Before long I found something that actually sounded good, I discovered the pedal point.

Within a matter of rehearsals I became obsessed with them. Every solo section had to have a pedal point, and I loved the power I had over the entire ensemble. Something I had never experienced before as a bassist. I definitely used them way too much and that only changed when I got to university years later and my professors kindly informed me that there was such a thing as too many pedals. Like breakdowns, as pedal points were in heavy rotation in my playing, they quickly became a staple in many of my arrangements. I also started to notice that many great arrangers used them to varying degrees in the music I was listening to.

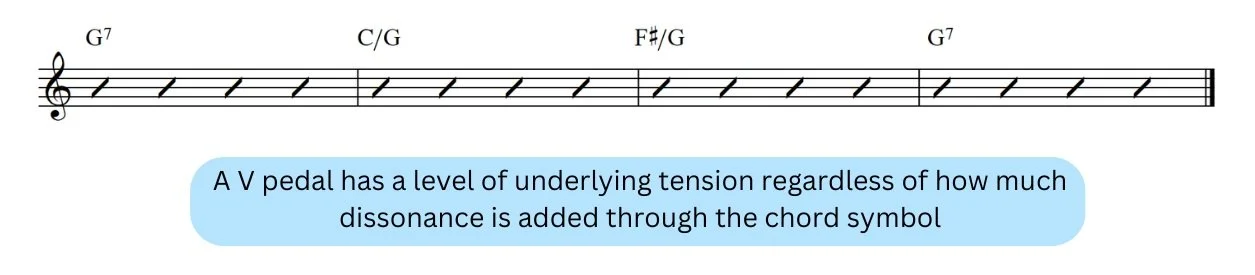

Unlike other sections, pedal points focus purely on the bass movement of a passage. Instead of jumping from chord to chord, a pedal anchors the bass notes of a progression to a single consistent note. The harmony is free to keep moving above but the bass note stays unchanged throughout. By remaining on a solitary note, you can create a considerable amount of tension, whether that be through anticipation of when the note may shift or by the relationship between any moving harmony above. As the pedal is stagnant it can handle considerably more dissonance than a standalone chord. This pairs beautifully with the fact that as soon as the bass note shifts away from the pedal it gives a sense of resolution, even if it doesn't move to a tonic chord.

There are a few ways to go about creating a pedal. By far the most common is the V pedal where the bass goes to the root of the V chord in a given key. As the V naturally wants to resolve, by having the bass note present, it captures some of that tension. From there you can create progressions above and simply just use them with the root of the V chord in the bass. Sometimes the chords will already have that note in them, in which case it will feel more like an inversion, and in other cases the note may be completely unrelated and add a lot of tension. For example, if G was the pedal note then C/G would feel less dissonant than F#/G. Both of the chords would have some level of underlying tension simply by having the G in the bass but the second option would come with a whole lot more dissonance.

Instead of relying on the inbuilt tension of the V for a pedal point, we can look at using similar notes shared between chords in a progression. To do this, we have to do a quick analysis of a chord progression to find what reoccurring chord tones occur, and then we assign one to be the pedal note. For example, in the progression Dm7 G7 Fmaj7 each chord shares the common tone of F. Once we place that as a pedal point the progression becomes Dm7/F G7/F Fmaj7. Unfortunately, this option can be hard to incorporate as many chord progressions simply don’t have a common tone shared between all of the chords.

To really sell a pedal it should be for somewhat of an extended duration. Otherwise it may simply just feel like an inversion or some kind of slash chord. By using multiple chords with a pedal bass, it signals that the bass isn’t going to shift and we start hearing the bass as its own entity alongside the moving harmony.

If we want to build more momentum with a pedal, we can also shift the bass note. This has to be done carefully because if the duration of either pedal note is not long enough or if we shift too often we may lose the pedal effect. Arguably the most popular way to do this is to shift up in minor 3rds which helps the pedal feel fresh but also maintains the momentum created.

Hay Burner

Sammy Nestico

Solo Sections

One of the key elements to jazz is improvisation. For many this will seem obvious but it’s still a section that can be integrated into a big band arrangement. The best part about solo sections is that the players do all the work for you! Whoever is improvising is literally coming up with the melodies on the spot and all you have to do is sit back and relax while they worry about how best to navigate the chord changes.

Jokes aside, as arrangers we still have some input into solo sections, namely through the development of background figures. By adding supportive lines in the horns we can help control some of the direction a solo takes, helping guide the improviser along a certain path. But when we are unsure exactly what a soloist may do, how can we make sure that we won’t step on them?

Unfortunately, there is no particular rule which states just how much or how little is acceptable when writing a background figure. Many times it is dependent on the individual improviser and what they like. If you’re lucky and know who might be soloing, you can talk with them during the writing process to gauge how much they like behind them at any one point. However, if this isn’t an option, there are a few other strategies we have at our disposal that will point you in the right direction.

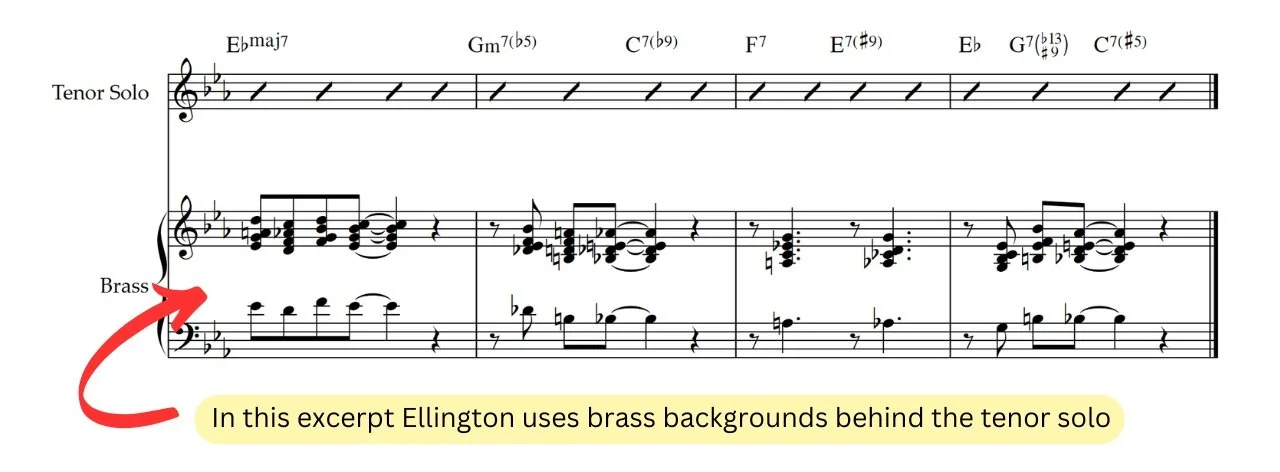

First is to think about which instrument might be improvising. As writers we can dictate this ahead of time, and even when we want to offer the chance for multiple soloists, we can limit it to instruments of one particular section such as the saxes. By doing so, we create a section where we know what the given timbre of the soloist may be and can assign packaging figures to contrasting instruments. For example, if it is a sax solo you could have brass figures, or if it's a trombone solo you could have sax figures. In the case where you double up and have the same timbre behind the soloist, you can look at incorporating mutes to help distinguish the soloist from the section.

Blue Goose

Duke Ellington

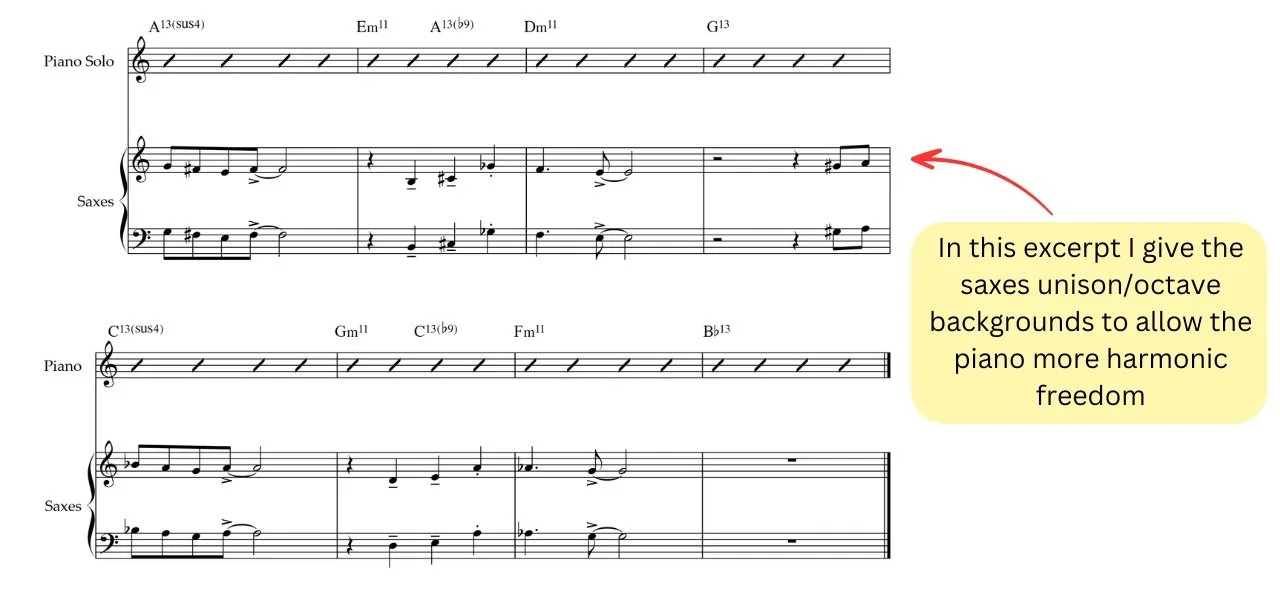

This idea can also be extended when a guitarist or pianist is soloing. Instead of worrying about similar timbres, we can instead think about the fact that both of the rhythm section instruments can play harmony by themselves. In order to give them the freedom to do so, we may lean toward unison backgrounds in the horns to avoid stepping on anyone’s feet.

Vesuvius

Toshi Clinch

Now that we know what instruments we might be assigning to a background figure, it’s time to tackle the question of what exactly makes a good backing line. When I first got started I had no clue how to write any sort of supportive lines behind soloists. Most of the backings I came up with made no sense and didn’t add too much to the arrangement. Worst of all is that I was aware that they didn’t really work but I didn’t understand why that was the case.

In 2019, I was given the opportunity to launch and run the house big band at a local jazz club in Melbourne. As there were already a number of bands playing original music in the scene, I decided to create a repertory ensemble that focused on the music of great big bands such as Basie, Ellington, and Mingus. It went off with a bang and still runs to this day even though I no longer live in Australia.

Through the process of gathering music for the band, I had the chance to look over hundreds of scores and learn from the very best. By comparing so many charts with one another, it became obvious that the successful backing figures all were treated like standalone melodies. They naturally led to a new section and contributed to the flow of an arrangement, and most importantly, worked regardless of whether there was a soloist or not. From this I realized the two most important aspects I needed to start including in my backings were a more melodic approach, and to have a better sense of direction.

Solo sections don’t just operate as phantom sections in the middle of a piece but as a conduit from one section to another. Just because they focus on improvisation doesn’t mean they can’t contribute to the flow of an arrangement. With this in mind, before we write a single note we can look at where a solo section starts and where it ends, taking note of the intensity and dynamics of both locations. If the solo is coming out of a screaming shout section, it makes sense that any immediate backing figures may be quite powerful and loud. Whereas if it was coming out of a quiet piano interlude, that wouldn’t be as appropriate. Looking to the end of the solo, if you are wanting to transition into a louder, more dense section, then the backgrounds should help make that feel natural by gradually building over time.

When we take this approach to backing figures, it also helps inform the soloist how they should approach improvising. All too often solo sections are treated as open segments for musicians to do what they want. However, great improvisers understand that their job is to craft improvised lines which complement the overall feeling of a piece. By shaping the backgrounds based on where an arrangement has come from and where it’s going, you force the improviser to treat the section in a certain way. Instead of being worried about stepping on their solo when you start adding louder horn parts, you can think of it as a way to signal to the soloist that they need to start increasing their own intensity and volume to match the arrangement. As it is coming from a place of direction, regardless of how an individual musician reacts, your decisions will be musically justified.

Shifting from planning to melody, once you have a framework for direction of your backgrounds, you need to start worrying about the actual lines themselves. There’s no one right way to go about this and like all melodies and countermelodies, what is considered good is subjective. In this context that isn’t the most helpful of advice, so here are a few strategies that I commonly use.

Restating the melody or other melodic fragments:

Nothing beats using the existing melody behind a soloist. It helps remind everyone where in the form you are and it is a line you know already works with the harmony. Alternatively, you can create a new melodic line from themes or fragments of melodies you have already used in the arrangement too.

Follow a guide tone line:

When in doubt, construct a backing figure from a guide tone line. Even if it isn’t the strongest of melodies it will at least reinforce the harmonic movement of a solo section.

Any of the common countermelody techniques:

Whether it be a riff, a pad, or some hits, all of the countermelody techniques discussed in the melody resource can make for fantastic backing figures. The best part is that they all can be layered over the top of each other which makes it easier when you are wanting to build toward the next section.

Oop Bop Sh’Bam

Arr. Gil Fuller

Interludes

Perhaps more popular in older big band charts, interludes are still a wonderful type of section that we can utilize today. In general, they operate as a link between two sections and often get used when the end of one section doesn’t neatly flow neatly into another. Such as when you get to the end of a melody section and write a nice conclusive phrase only to realize that you planned to transition into a solo section. Or maybe you have multiple solo sections and want to split them up with some sort of band moment in between. These are the moments when interludes shine.

Typically, an interlude is shorter than the standard section, often being about 4 bars long in the average medium swing arrangement. Just long enough to make one significant statement and then get out of the way for whatever comes next. As for the content that you fill them with, that is completely up to you. The most successful interludes are informed by the sections on either side and operate primarily as transitions.

Avenue C

Buck Clayton

Intros & Outros

Moving onto a completely different kind of section, intros are fixed to the start of a piece and help establish the tone of an arrangement. Think of any blockbuster movie you’ve ever watched, what you hear right at the beginning usually sets the tone for the rest of the movie. For example, if it’s an animated Disney movie you hear the wonderful When You Wish Upon A Star theme, which pulls on nostalgia and is played in a heart warming manner. Whereas a horror film may start with highly ambiguous dissonance that instills a sense of fear and chaos. Intros operate in exactly the same manner and give a taste of what is to come.

On the flip side, outros help conclude a piece and can leave the listener with a lingering emotion. Do you want the chart to feel complete, with everything resolved? Or perhaps you want to leave it open ended? Maybe there was something important you want to reiterate. All of these are valid approaches to an outro and can create unique conclusions to an arrangement. Although often overlooked, if you have a good intro and outro, they can do a lot of the heavy lifting when it comes to the impression a listener will be left with. People often don’t remember what happens in the middle but the first and last notes that are played can leave a mark.

Unfortunately, like everything else in the composition world, it is hard to point to one specific way to write a successful intro and outro. Everything is subjective and based on the context of a piece. However, I can show you examples of what has worked for others which can then help inform the decisions you make when you write your own intros and outros. So let’s start with common intro techniques.

One of the most frequently used devices to start a piece is to take the last few bars of the melody. It kind of works as a sneak peak of what is to come and is a very quick way of getting an intro on the page that you know will work. You’ll see this most often with vocal charts where it acts as a reference point and cue for the vocalist to enter at the top of the melody. But it is also viable for instrumental music too.

Another approach is to take one of the major themes present in the melody and augment it in some way. That could be through repetition, inversion, reharmonization, displacement, or many other techniques, however you want to make sure that no matter how far you stretch the theme that it’s still recognizable. Similar to the previous method, the key to thematic intros is that they hint at what's to come later. In my opinion, these are the most fun to experiment with and you can create some amazing lines with only a small number of notes.

Don’t Git Sassy

Thad Jones

Instead of creating something new for an intro, we can also draw inspiration from some of the other section types we’ve mentioned earlier. If you approach the start of a piece with the mindset of writing a shout section, a pedal, or a vamp, you’re going to create vastly different results to the above techniques. Yet, all of which are still completely viable options.

Come Fly With Me

Arr. Quincy Jones

Manteca

Arr. Gil Fuller

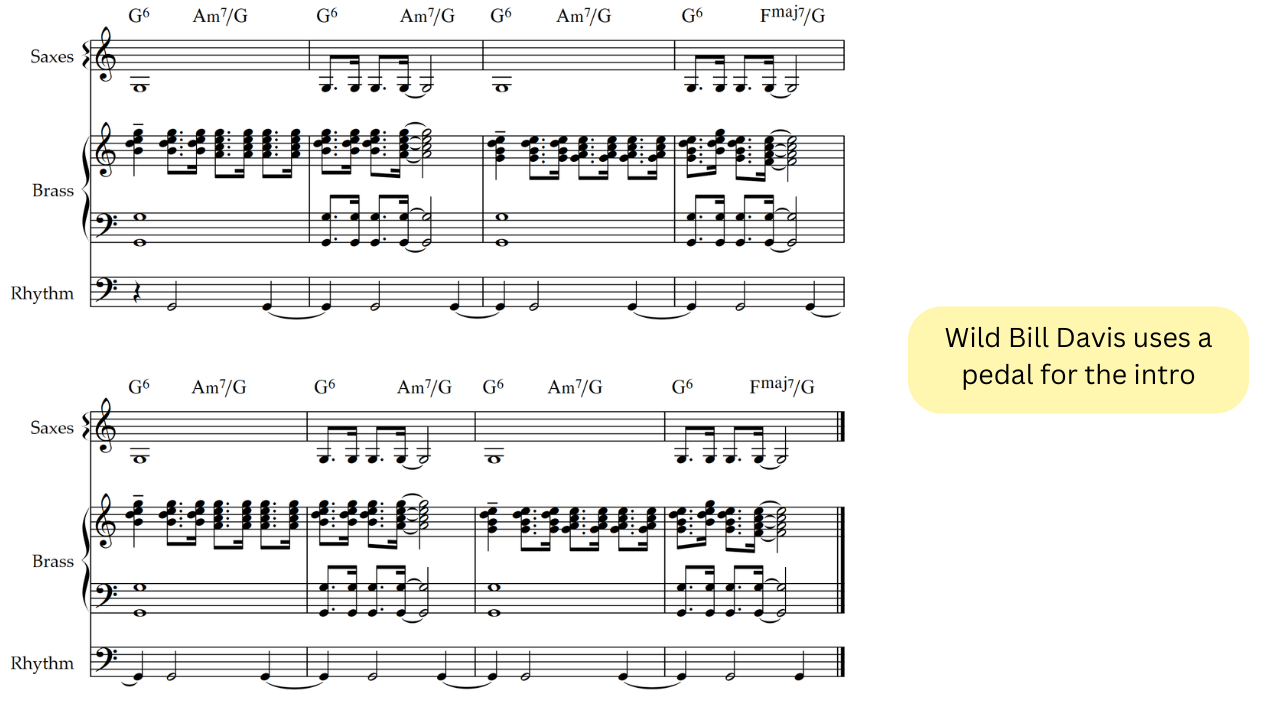

April In Paris

Arr. William “Wild Bill” Davis

Moving over to outros, there are a number of different techniques to look at. First off, sometimes an outro is simply not needed if the melody already ends conclusively. Think about how many times you may have heard a jazz standard finish when it got to the end of the form. A big band arrangement is no different and many times it is acceptable to not include an outro. However, if you do want to include an outro, by far the most used option is the tagged ending.

A tag is when you take the last phrase, usually two or four bars, and repeat it a few times before ending. The most common variation is playing the phrase three times alongside some kind of harmonic turnaround. If you are looking to spice up a tag, you can look at completely reharmonizing it or sidestep the harmony for one of the repetitions. There are plenty of options, each of which provides a slightly different flavor.

Sometimes it feels better to end a piece on a held long note, however, that doesn’t mean that all of the instruments have to arrive at that note at the same time. Instead, you can delay certain sections while the melody is held out elsewhere. A prime example of this is when the melody is being sung by a vocalist and the band has figures under the final note. When this happens, the band will usually have some sort of conclusive tutti line that lasts for a small number of bars (so the singer doesn’t run out of breath) before landing on the held note. This type of writing can be quite powerful and really establish a conclusive end to an arrangement.

Come Fly With Me

Arr. Quincy Jones

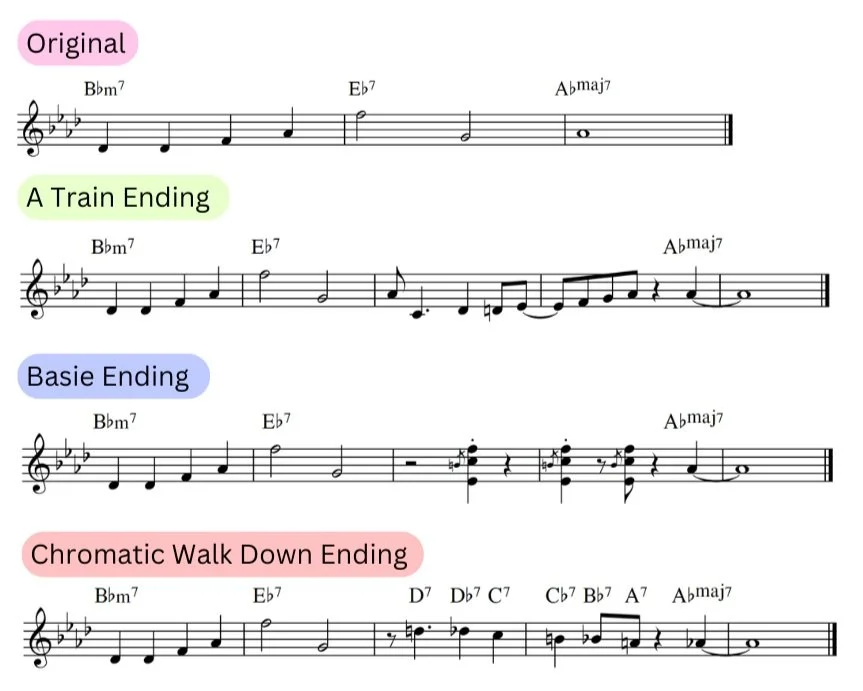

Of course, if you don’t want to hold out a long note you can still write the same sort of conclusive figures by themselves. Some of the go-to staples include the A-Train ending which comes directly from Take The A Train performed by Duke Ellington, the three chord Basie ending where a solo piano plays three syncopated chords in the upper register before the final band note enters, and a chromatically descending walk-down from the b5 of a key to the root. All of which have been used countless times across hundreds of charts and are popular for the same reason, they work.

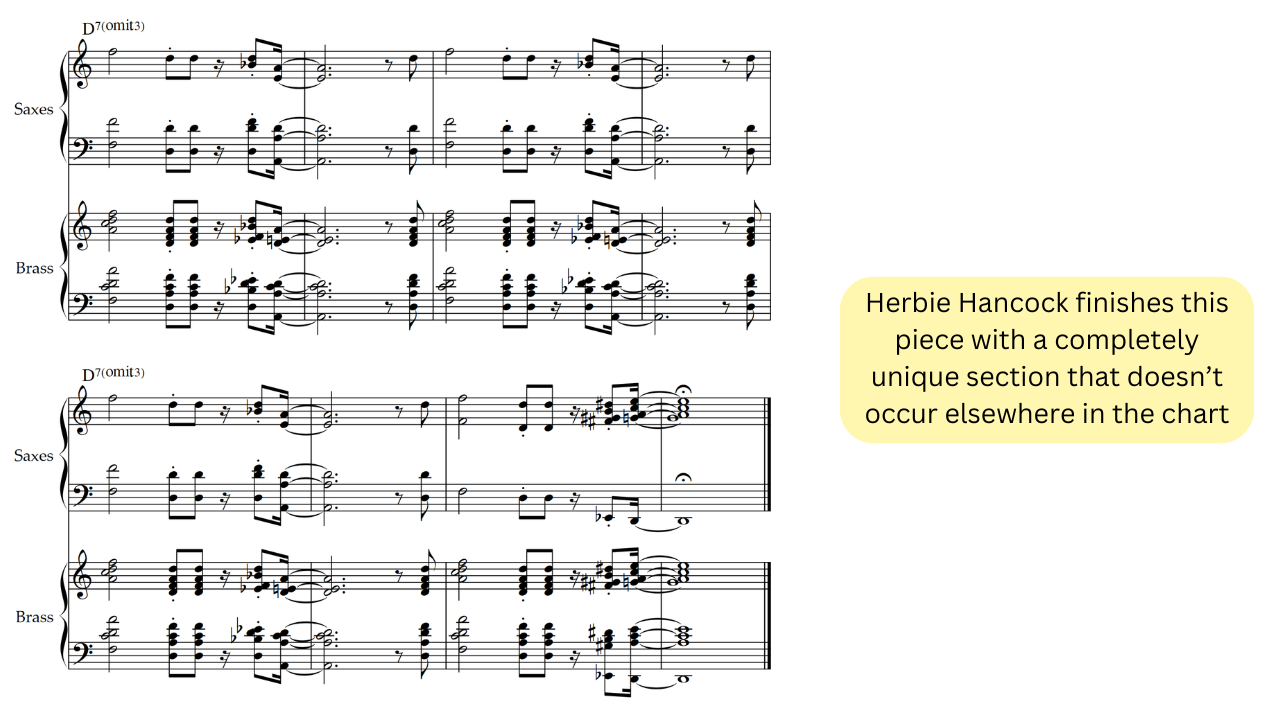

If you’re feeling creative, another way to conclude a piece is to introduce a brief new theme, something which hasn’t been played elsewhere in the arrangement. By doing so, you leave the listener with a final little present which often turns into them wanting more after the end of the chart. It also helps an outro standout as a unique section that can stand alongside any of the other sections we’ve discussed.

Spank-A-Lee

Arr. Toshi Clinch

Similarly to intros, we can also draw inspiration from other section types. Whether it be the melody, a solo, shout, vamp, pedal or any other section, you have plenty of options to explore with each of them being a viable ending to end a piece. Whichever way you choose to go with an intro or outro, the most important point to remember is that they set the emotional tone for an arrangement. Regardless of whether it’s at the start or end of the piece, both sections leave a lingering impression which can be powerful if utilized correctly.

Cross-Pollination

All of the sections we’ve discussed don’t just stand alone as isolated parts of an arrangement. Instead, many of the elements can be integrated into one another and blur the lines of the terminology we use to name a specific section. For example, you could incorporate a solo alongside a shout section, or maybe a breakdown which uses a pedal, or perhaps a soli which is built on a vamp. There are endless possibilities, each of which shape an arrangement in different ways. Here are a few examples to give you an idea of what others have done.

The Takeaway

Sections are the building blocks of an arrangement. You can treat them independently, mix them together, and really go wherever you want with them. Each has a different flavor that is identifiable and has the potential to be the standout moment in a chart. When you’re just starting out I’d suggest getting comfortable with each of the sections listed on this page one at a time. Eventually, you’ll start using them together and then can look elsewhere for more inspiration.

Now that you have a good idea of everything that goes into writing an arrangement, it’s time to look at the next important part, formatting. It’s no good writing an amazing chart for it to be unreadable when you bring it into a rehearsal. But you’ll have to read that on the next resource as this page is already pushing the 10k word count and I think that anymore might be a bit too much.