How To Craft Melodies

& Countermelodies

In jazz arranging there is one topic which is harder to teach than any other. So much so that it’s often not included in the syllabus of many courses due to its subjective nature. However, as it’s an essential component in arranging, I’m going to try my best to help you tackle the topic by introducing some techniques that have helped me along the way. So what am I alluding to? Well unless you somehow missed the title, I’m talking about composing melodies.

Defining what is a “good” melody and what is “bad” often depends on the music someone has been exposed to and what their general interests are. For example, the popular music in the USA isn’t always popular in other cultures. It’s not because it’s “bad,” it’s just that if you aren’t born into a western society, you may have a taste for something which sounds completely different. To complicate the matter further, there are often many different elements in a given melody that you may be drawn to while others you may not. Perhaps the lyrics are great but the note choice is less than ideal. Or maybe the actual melodic line is great but the rhythm is uninspiring.

For me, it took a while to be drawn toward the dissonance and color of jazz. As I grew up in a rather musicless white Australian family in the suburbs of Sydney, I was introduced to music through whatever 90s hits were being played on the radio as well as a few specific tracks that my parents would play on long road trips. I think Seal’s “Kiss From A Rose” will permanently be engrained into my mind thanks to my mum.

It wasn’t until I moved to Melbourne and started playing bass in high school where I was immersed in music that I actually enjoyed. Within the span of maybe 2 or 3 years I was introduced to artists like Count Basie, Herbie Hancock, Michael Jackson, Earth, Wind & Fire, Gordon Goodwin, Stevie Wonder, Marcus Miller, Ray Brown, Jaco Pastorius, Oscar Peterson and many more. My musical taste had very much been drawn towards jazz, not because of the harmony or melody, but because of the amazing sense of rhythm that swing and funk provided.

Over time I started to learn more about jazz and I started to fall in love with the complexity that the harmony offered. However, it took much longer for me to enjoy genres like bebop and modern jazz which seemed to push the comfort zone of my teenage self just a bit too far. Now that I’m somewhat immersed in the artform, there are still artists whose music I don’t enjoy even though I understand and respect how they created it. I find myself somewhere in the zone of loving jazz but not being an absolute diehard, allowing myself the space to enjoy a large offering of styles and taking inspiration from wherever possible.

The reason I share this with you is so that you can see where I’m coming from when I discuss what I think makes a “good” melody. You may disagree with me and that’s completely okay. The melodies I am naturally drawn to come from a certain arena of recorded music, and it’s likely that you may be drawn to contrasting songs to me. The beautiful thing is that we will both be able to create unique melodies that we believe sound “good” even if they sound different to one another.

To try and remove bias from the equation, I like to teach composition by establishing a rubric of characteristics that every melody includes. That way regardless of which melodies we define as “good” and “bad,” we can have a better idea of what goes into them and find the elements which we like and don’t like. Throughout this page I’ve tried to include as many techniques which I draw upon when composing but it is by no means an exhaustive list. Sometimes the best melodies don’t come from a technical place and may simply arrive while you are in the shower. There’s not much that can be done to explain those moments in an academic manner, so I offer the following techniques as a way to brute force inspiration when necessary. Remember, it’s always easier to edit than it is to create, so these methods are here to help you write the first draft of a melody, to help the creative juices flow, and hopefully put you in a place where you can refine the idea into your dream melody.

What Makes A Strong Melody?

Although subjective, I like to think of a strong melody as one that gets stuck in my head. A common experience that I’m sure everyone can relate to. There are a number of elements which can help make a melody memorable, however a song doesn’t need to include them all to be considered “good.” In fact, these days most songs on the radio might only focus on one or two yet still seem to be popular. For me, the core ingredients to a melody include: range, motion, repetition, and rhythm. Of course you can throw lyrics into the mix too but I’m going to restrict this resource to purely instrumental music for simplicity. Although these elements are applicable to today’s music, I was actually introduced to them through the analysis of classical composers such as Beethoven and Mozart.

Range

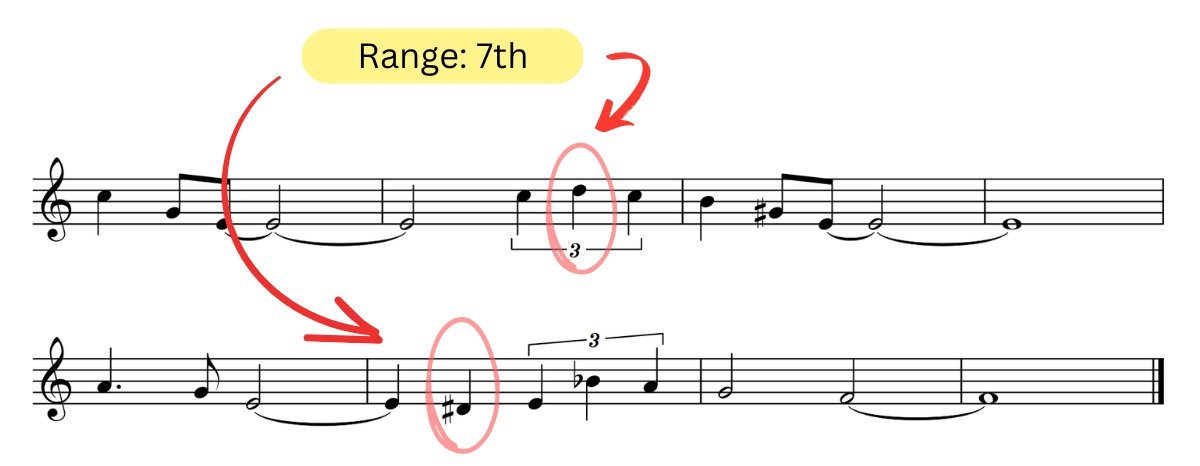

In 2015, while attending a class on 18th century counterpoint, my professor decided to break from the set curriculum and spend an hour or so talking about melody. Somehow even with a decade passing and forgetting nearly everything mentioned in that semester, how Paul Dworak unpacked melody has stayed with me and played an integral role in my composition process. First he defined that most melodies have a set range of between an octave to an octave and a fifth so that they can be easily singable. Applying this logic to instrumental music also works quite well as it limits lines to the better part of one register. Taking a quick look at a few of my favorite melodies we can see that this theory checks out.

Fly Me To The Moon

Bart Howard

All Of Me

Simmons & Marks

He then explained that we can reverse engineer this information when composing our own melodies by defining a desirable range before even writing a single note. From there the process is to work out where in the range you plan on starting your melody, end the phrase, and where the high/low point may land. Dworak demonstrated one possible option where you start with the root, make a large leap and then slowly return to the root again. However, there are many ways you can approach this exercise and by looking at a few melodies you can get a feel for how other composers navigate the range of their melodies.

Blue Bossa

Kenny Dorham

Motion

By mapping out the range over a number of bars we are left with a loose melodic foundation. In its current state, there isn’t much of a melody so to speak so we need to start incorporating some of the other elements to add interest. As this concept was being taught through an 18th century counterpoint class, Dworak was sure to remind us that we had to follow a strict set of rules that were common to the period. These days this is considerably less important to worry about but there are still some useful points that can be utilized. One of which is the idea of motion.

In classical counterpoint, the general rule is that melodies move smoothly by step where possible. When a leap takes place, the melody must then move in the opposite direction by step. For example, if you had a melody that jumped upward from C to G, it would then have to descend by step.

There’s a bit more nuance to it in the counterpoint world, but for the purpose of composing melodies it provides a great framework for motion. By always moving diatonically, we create smooth lines which naturally resolve through the key we are in. And when we inevitably break from that with a leap, we stabilize the melody by returning to stepwise motion in the opposite direction. It is also a great way of continuing the motion of a line when you hit the parameters of your outlined range. Instead of going outside of the range, you just displace the melody note by an octave and continue in the same direction.

Somewhere Over The Rainbow

Harold Arlen

Blue Bossa

Kenny Dorham

Alongside stepwise motion, arpeggiation offers a wonderful way to add leaps into a melody while avoiding the angular feeling often associated with using multiple leaps in a row. They can also help reinforce the feeling of the accompanying chord progression and quickly connect large intervals more efficiently than scalar lines. By using a combination of arpeggios and stepwise motion, you can come up with a large number of ways to traverse your selected range. Not to mention, it is one of the most popular methods that great composers have used.

Misty

Erroll Garner

Although stepwise motion and arpeggiation do the heavy lifting when constructing a melody, there are certain melodic devices which can be incorporated to help add interest. Namely, approach tones, neighbor tones, and enclosures. To use any of the three techniques, we must first designate some kind of target note in our melody as each method is used in the approach of a given note.

Approach tones are the most broad out of the three, and simply refer to a note that is located either a whole tone/step or semitone/half-step above or below the target note. Typically in jazz these are used chromatically and can be used multiple times in a row to increase the feeling of resolution. For example, if G was our target note then a lower approach tone would be F#. You could then use F as another approach tone into the F#. Whole tone/step approaches are far less common and are generally used when you want to approach a target note diatonically. For example, in the key of C major if you were to approach the same G target note, you could use an F or A.

Neighbor tones on the other hand are similar to approach tones but occur specifically between two of the same notes. For example, if you have two Gs then you could place a neighbor tone between them. Like approach tones, neighbor tones can be either a whole tone/step or a semitone/half-step above or below the target note.

Last but not least are enclosures, which combine two different approach tones together before resolving to a target note. They get their name from the shape they create where the target note is theoretically enclosed between the approach tones. This method is widely used in jazz and can use any number of combinations of whole tone/step and semitone/half-step approach tones. For example, using the same G target note as before, an enclosure must include some kind of F or F# as well as some kind of A or Ab. It doesn’t matter which note comes first, as long as they both sound before resolving to the G. A diatonic enclosure would utilize the notes of the given key, whereas a chromatic enclosure would use the notes a semitone/half-step away from the target note.

Anthropology

Charlie Parker

Repetition

No matter what option we use to write a melody, there is one element which can help validate anything we come up with: repetition. However, if we don’t like how a passage sounded in the first place, repeating a subpar phrase will only amplify the original issues. Fear aside, repetition may be one of the most underrated tools in a composer’s arsenal.

Early in my composition journey I felt it was necessary to come up with something new every single bar, trying to make each melody feel unique. To be honest, the process felt exhausting and for some reason I thought that repetition wasn’t a viable option. That was until I listened to an interview by the great film composer John Williams where he was asked a question about his use of thematic material in films. I can’t remember his exact response but the main point was that if you come up with a great theme that it can be used as many times as necessary. No one gets bored of a good melody and it not only helps connect parts of a composition together but is also a more efficient way to write.

If you take a closer look at some of the scores John Williams has written, you’ll see he follows through with this concept. You don’t need to go far to see that the melodies from the Harry Potter series and Star Wars franchise get used in high rotation throughout each film, yet each time it never seems to feel boring or overused. With this approach in mind, I started to use repetition in my own compositions but perhaps on a smaller scale than how Williams’ approaches a 2 hour blockbuster score. I would create small self-contained melodic fragments and then repeat them a number of times throughout a piece. What I found was that it made an arrangement feel cohesive and I never found a point where it was too much. I could take a theme and use it as horn backgrounds or as a counterline for another melody, and by focusing on a small idea at a time, it felt quite manageable.

Ironically, the more I started using repetition, the more I realized how so many great melodies have repetition inbuilt into them. Whether it’s from a form perspective such as having three A sections in an AABA form, or something much smaller such as a phrase in a melody being repeated, jazz and popular music is littered with examples of repetition.

Honeysuckle Rose

Fats Waller

There are also other forms of repetition which help avoid creating monotony within a melody. Surprisingly, one of which was also introduced to me through my theory classes with Professor Dworak. The technique is called sequencing, and it’s when you repeat a phrase but instead of copying it verbatim, you raise or lower it slightly. This can be done in a relatively small manner where the phrase may be shifted up a tone diatonically, or by a larger leap such as in the case with the blues where you might shift a passage up a 4th over the IV7 chord. It is a great tool which augments the melody just enough that sometimes you don’t even notice it was repeated at all.

Black Orpheus

Luiz Bonfa

Fascinating Rhythm

George Gershwin

Similarly to sequencing, we can adapt repeated phrases with slight changes to make them feel fresh. These adjustments can come in all forms including melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic differences, with the first of which relying on some of the techniques we’ve already discussed. When you repeat a phrase you can alter the melody slightly by adding embellishments. These may include enclosures, approach tones, neighbor tones, as well as other options such as turns. It should also be noted that when you repeat a line which already includes these embellishments, you can also remove them to create a point of difference.

Unlike melodic alterations which focus on adding or removing embellishments, harmonic changes are when you modify the underlying chord progression of a repeated passage. Sometimes the original melody line will work over a new set of chords and other times you may need to change a note by a semitone/half-step to accommodate the new progression. In my experience, using this method can help you stretch repeated phrases out for quite a long time before they start feeling stale as each repetition brings a new harmonic feeling. There are so many ways you can change a chord progression, many of which I cover in other resources, so for more information you can check out the harmony section of my resource page.

One Note Samba

Antonio Carlos Jobim

Instead of focusing on the notes, we can also adapt the rhythm of a repeated melody to make it feel somewhat unique. Although we haven’t covered rhythm in detail yet, a great way to vary a repeated passage is to displace the rhythm in some way or another. That could be moving a phrase to start earlier or later, or perhaps making a line more syncopated.

Straight No Chaser

Thelonius Monk

The real beauty of all of these different repetition techniques is when you start combining them together. Yes each of them can stand alone, but when used alongside one another, you can stretch the same phrase for a considerable amount of time without it ever feeling bland. With this in mind, some of the most popular jazz standards are simply repetitions of the same two bar melody just with slight variations. And if it works for those melodies it can work for yours too.

Rhythm

Right next to the notes we choose are the rhythms we assign them. In jazz, rhythm plays quite a large role in defining the feel of a melody, and more notably is an important factor when trying to write a line which swings. However, what exactly makes a phrase swing can be quite hard to describe with it often being easier to highlight passages which don’t feel right than being able to articulate the exact issue. To clarify, when I use swing in this context I don’t just mean melodies which have a swung quaver/eighth note feel, I mean phrases which line up with the groove and bring out the pocket of the swing feel. If I was to take any straight melody and simply apply a swung feel to it, most lines wouldn’t feel right, almost as if they were going against the grain. This is due to the context of jazz and swing music establishing a vocabulary of rhythms over time which we now hear as “right.” Although it’s hard to justify feeling in theoretical terms, there is one technique I picked up from my studies of Cuban music that surprisingly can help us write a swingin’ melody.

Unlike most Western music which is built around a one bar structure like the 4/4 time signature, many Latin American styles follow a two bar phrase structure built around a recurring clave pattern. One day while attending a class by Puerto Rican drummer and percussionist Jose Aponte, he explained that within the clave pattern there is almost a yin and yang effect which takes place with one bar reinforcing the down beats and the other the off beats. Interestingly, this provides a fantastic framework for writing melodies which swing and helps introduce the idea of balance between syncopation and down beats within a phrase.

In jazz most melodies have a mixture of syncopation and down beats, whether it be at the start of a phrase or the end. However, unlike clave there is a slight preference toward syncopated rhythms. By looking at melodies through this lens, it starts to reveal how certain rhythms may feel more appropriate in a jazz setting. Generally when a melody doesn’t feel like it swings, it’s because there are more down beats compared to off beats. Using too much syncopation may also feel inappropriate at times but is by far the safer option out of the two.

A great place to start is to replicate clave’s 50/50 balance of syncopation and down beats. What that looks like in practice is having the start of the phrase emphasize one option with the end landing on another. Once you feel comfortable with this you can look at larger phrases where you may highlight more downbeats initially and then in the latter bars use more syncopation. Eventually you will have a sense of when a melody needs more of a particular option, and you’ll likely start to incorporate more syncopation than the 50/50 ratio we initially started with.

Billie’s Bounce

Charlie Parker

Now that we have a solid foundation of what makes a phrase swing, we can shift gears and look at how rhythm can be used to bring emphasis to notes as well as to create contrast between phrases. There are two major factors which impact the strength of a given note: the duration and which beat it is placed on. Starting with duration, the longer a note sounds compared to those around it, the more attention it will be given. We can use this to our advantage when composing by elongating notes we want to be more prominent and reducing those that perhaps are less important.

Moving to the second factor, the beat on which a note lands can impact how we feel it. Some add weight while others may accentuate a given note. For example, beats 1 and 3 feel rather solid bringing nothing special to the table and are generally seen as the status quo. Whereas landing on beats 2 and 4 give considerably more weight which results in a phat sound. Offbeats generally feel lighter and have a level of anticipation associated with them.

The trick with duration and beat placement is to use them together to create standout moments in your melody. For example, if you want to bring extra attention to a note, perhaps you make it longer than those surrounding it and put it on beat 2 or 4. Additionally, knowing that you want the given note to have more attention, you could surround it with phrases made up of offbeat quavers/eighth notes which feel completely different.

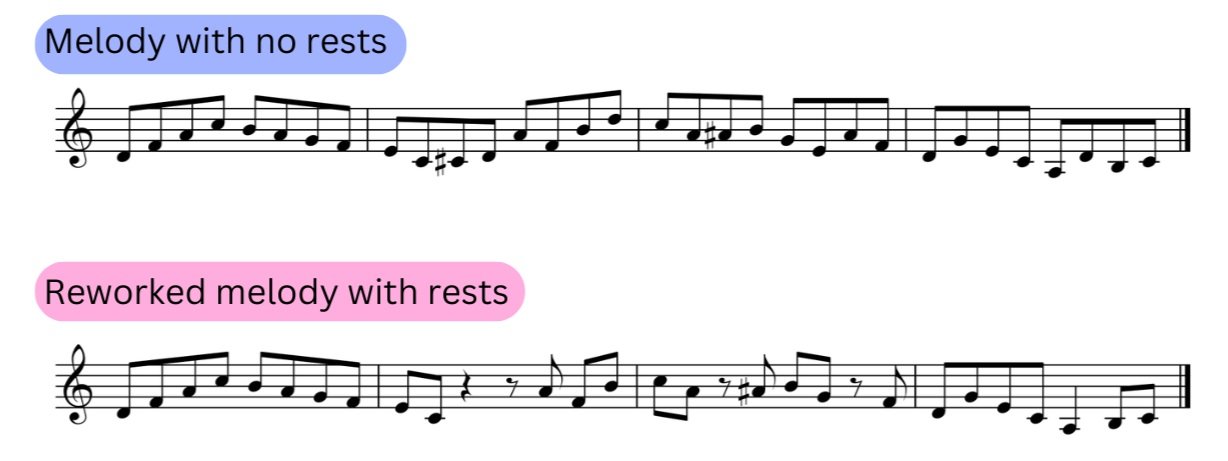

Another trick at our disposal is to mix multiple rhythms together to create variety in our phrases. When we rely on any single rhythm for too long it becomes stale. If you find this happening in your writing try to break up your melody by including tuplets, quavers/eighth notes, crotchets/quarter notes, as well as any other different rhythms that come to mind.

On the other hand, instead of thinking about adding more rhythms, we can look at the opposite and try to incorporate space into our melodies. As a bassist, this idea was introduced to me one day when I was learning about improvisation from my teacher Lynn Seaton. One of the common habits of rhythm section players is to create large strings of notes when they solo as their instruments don’t require air to play. Sometimes this can work out well but sometimes it lacks a certain organic feel that horn players have when they improvise. Lynn’s suggestion was to breathe out while improvising and to forcibly stop a phrase when you had to take a breath. As a result I was able to play more digestible phrases which had breaks to allow the listener to process the music which had been played.

Surprisingly this approach can also be used while composing melodies but instead of breathing out you simply sing the lines you write. By doing so, you’ll understand where performers may need to take breaths which you can then use to create natural breaks in the music.

Creating Emotion Through Emphasis

As I said earlier, a solid melody doesn’t have to prioritize every element we’ve discussed. In some contexts there are melodies which are widely popular that repeat one or two notes and rely purely on the lyrics, while others the motion and note choice do the heavy lifting. The key is to understand the options at your disposal and how you might be able to use them when composing. However, when you do choose to combine multiple factors with one another you have the chance at creating special moments in your composition.

Up until now we have focused on the technical aspects of composing, which is definitely one part of the process but it’s not something that most people think of when they listen to music. Most people relate to melodies because they evoke some kind of emotion and couldn’t care less about the range, motion, repetition, or rhythmic aspects being used. So to take our melodies to the next step we have to start thinking about how we can incorporate emotion into our writing. To do so we have to start looking at how each element can work together to emphasize certain feelings. As we are mainly focusing on composing melodies on this page, I won’t stray further than the elements we’ve already covered but it should be noted that orchestration, timbre, articulation, style, and harmony can also play a role in establishing emotion.

To create emotion we need to understand how we perceive chord tones. Such as a #9 feels funky or gritty depending on the context. Once we have built that perception we can highlight certain notes in our melodies to emphasize that emotion. Using the techniques we have already unpacked, there are many ways we can bring attention to a given note. It could be the high point or low point of the range of a melody, it could have a longer duration than surrounding notes, it could be placed on a more prominent beat like beats 2 and 4, it could be repeated a number of times, or it could be a combination of all of these approaches.

Alternatively, we can emphasize a given note by changing its surroundings. If we know which note we want to stress, we can make it stand out by contrasting the phrases before and after. For example, if the given note is going to have a long duration, we can make the surrounding rhythms shorter, if it lands on a down beat then have the other phrases include more syncopation, we could avoid using the given note elsewhere, and we could make sure not to write any other notes which may overshadow the given note.

There are definitely a lot of amazing options at your fingertips to evoke emotion from your melodies. Regardless of how you do it, I would suggest that you try and compose from an emotional place more than from a technical mindset. It will naturally result in more organic and relatable lines and you’ll likely find more satisfaction in the end result.

Copy From The Best

Sometimes creating a brand new melody can feel very overwhelming. I know I definitely prefer arranging a pre-existing melody more than coming up with something unique. If you find yourself in this position there is another option which isn’t quite as daunting as creating a new melody from scratch. It’s even something that a lot of other composers do, including Marty O’Donnell the writer behind the legendary theme song from the game Halo.

As an intrepid lover of video games, I often find myself going down the rabbit hole of behind the scenes interviews. I’ve spent many an hour scouring the internet looking for rare footage and with Halo being one of my all-time favorite games, I’ve naturally watched a significant amount of interviews with its composer Marty. One of the more regular questions he gets asked is how he came up with the original theme for the game. Due to time restrictions he was tasked to compose a main theme for the first game in less than a day. Quite the accomplishment given its impact on pop culture.

While driving his car he tried to think of other great melodies and The Beatles’ Yesterday came to mind. In only a couple of minutes he mapped out Lennon and McCartney’s melody in his head and used it as a framework for the opening theme of Halo. He changed a few aspects to match the aesthetic of the game, but the motion of the melody still followed the same direction as The Beatles’ classic hit.

When we approach composing a new melody we can try to create something from scratch but if we don’t feel confident, or maybe don’t have that much experience, there’s absolutely no problem to take inspiration from other great melodies. By analyzing a given melody through range, motion, repetition, and rhythm, we are able to create a pretty good template that we can build off of for our own compositions. Similar to what we explored in the Event List resource, the end result will generally come out quite different from the original and feel unique to you. Over time, you’ll find elements of different melodies you like and gain the confidence to write your own melodies using the tricks you’ve picked up along the way.

Countermelodies

Often countermelodies receive somewhat of a bad wrap compared to melodies. For one reason or another, many people look at them as if they are inferior when in fact countermelodies typically introduce a point of interest that captures the listeners attention more than a melody. We need to make sure that we give them adequate consideration and treat them with as much care as when we write melodies. Otherwise they may take away from the music.

There are many different ways we can approach writing a countermelody and at its essence we can treat the process exactly the same as how we just looked at writing a melody. However, as a countermelody exists alongside a given melody, there are some established techniques that arrangers often use that we also have access to. Namely: riffs, pads, hits, call & response, and counterpoint. The best part about writing a countermelody is that there is already some level of context such as a chord progression and melody to work with. These help inform which notes we might want to choose and the spaces where we may want to locate the countermelody. Something which I find very handy compared to composing everything from scratch.

As with any form of composition, how we perceive countermelodies is subjective too. Unlike the first portion of this resource though, due to having some level of context and a number of pre-existing methods, we can think of countermelodies as not only being creative but also functional to some degree. Where on one hand they operate in a similar capacity to a melody but on another serve a different role in the arranging process. As such, I’ll be focusing more on the functionality of a countermelody and aspects you should be aware of when writing them more than the creative process we looked at earlier. So let’s jump into it!

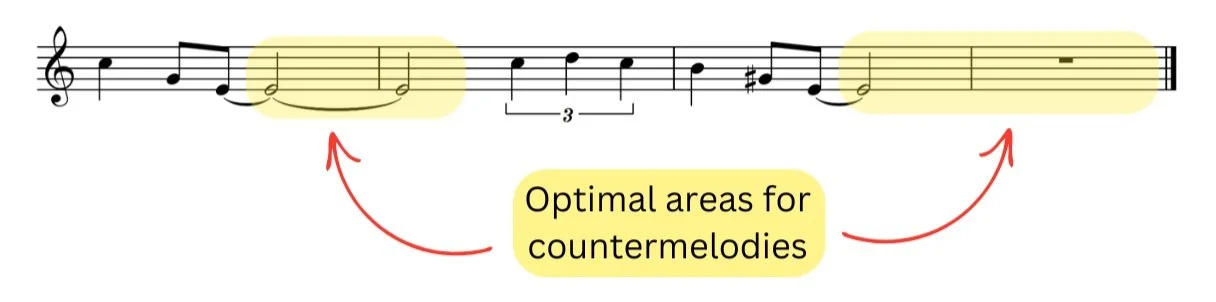

Finding A Location

The key to any good countermelody is placing it in a way which complements the original melody while also allowing it to standout for itself. To do so we must first locate a space to write the countermelody. The most obvious choice is for it to take place while the melody has some form of rest, that way we can avoid any clashes. However, most melodies don’t have long sets of rests but do have the next best thing, held out notes. The only difference is that we need to be mindful of the note that is being held and how it may impact the countermelody harmonically. For example, if the held out note was a G then any kind of 3rds or 6ths in the countermelody would create a stable sound whereas a 2nd or 7th may add unwanted dissonance.

Sometimes there are moments where you want the countermelody to play alongside the melody. These are a bit trickier to handle as there are more chances that the notes and rhythms of the both lines will affect each other. The general premise to handling these situations is to understand which line you want to have more attention. That way you can emphasize it by using more motion and a higher density of rhythm while leaving the second line to play a more passive supportive role. In some cases you may have two highly active lines working together, which is considerably more complex to handle and will require a high level of care to get right. It’s definitely not impossible to pull off, it will just require a delicate touch and maybe a bit more time to get right. Fortunately, as we explore some of the common countermelody methods later on, we will cover some strategies I’ve picked up to handle these sorts of situations.

Implying Harmony

By having an existing melody note as well as a chord progression, there are a few more limitations to composing a countermelody that we may not usually have. However, both allow us to have a better chance at implying harmony through the lines we write instead of relying on large voicings or the rhythm section. To do so, we can try to capture the scale sound of the accompanying chord symbol by using chord scale theory. If you aren’t sure what that is, you can read more about it here.

The key is to land on notes which best represent the sound of a given chord, whether that be the 3rd and 7th to imply the quality, or specific extensions or alterations to represent the color tones. One of the most common ways to navigate this type of writing is by creating guide tone lines through a chord progression which show how each chord tone wants to resolve. Depending on the chords used there may be dozens of different paths you could take, especially when you start factoring in extensions.

To create a guide tone, the general rule is to pick a note of one chord and then see how it may relate to the proceeding chord. Sometimes it will be within the chord, in which case the note will stay as it is, or in other cases it might have to move by semitone/half-step or whole tone/step. The goal is to create a path of least resistance and avoid leaps where possible. Also be aware that notes that move by semitone/half-step have the strongest pull and will feel the most natural when used. If you were to have a situation where you could resolve by semitone/half-step in one direction and by whole tone/step in another, the semitone/half-step movement would feel more comfortable harmonically.

With that in mind let’s have a look at an example. Using only the fundamental notes in a ii-V-I progression we can get the general idea. If we were in C major, a possible guide tone line between the three chords (Dm7-G7-C6) would be F-F-E, another would be C-B-C. Both of these use the two main semitone/half-step resolution options which go through the 3rds and 7ths of the chords. Alternatively you could also do D-D-E or D-D-C, as well as A-G-A or A-G-G if you want to pass through the other fundamental notes.

Once we‘ve established a guide tone line, we can start to build melodies off of them. This doesn’t mean that the melody has to be restricted to just one note per chord, although that is definitely an option, instead it means that somewhere in your melody you highlight the resolution between chords. Alongside those resolutions you are free to flesh out the melody using whatever technique you feel most comfortable and if you are wanting to better represent the accompanying chord symbol you’ll use notes from the accompanying scale. There’s also no reason you can’t try to highlight more than one guide tone line at a time or cross between them, however this is a lot harder to do.

Another way of approaching a countermelody is by harmonizing certain target notes with the melody. The principles are similar to how I unpacked 2 horn voicings here, with the main concept being that you should understand how intervals between the notes feel independently as well as how they relate to a given chord symbol. Typically, I will locate target notes which overlap with the melody, identify an interval that feels appropriate between the two lines and works within the chord symbol, and then create a countermelody built off a guide tone line. That way it doesn’t just feel like a harmonized melody line but instead two unique lines which briefly overlap with one another.

As with any type of harmonizing, you will need to make a choice as to what options you want to prioritize. In this case some of the options include: the target note, the interval between the lines, the relationship between each line and the chord symbol, the melodic nature of both lines, and the guide tone resolutions between chords. If you’re lucky you’ll find a solution which lines up with everything but if not, make sure you know which options you want to prioritize and why.

Riffs

Now that we’ve established where to locate and write a counterline as well as what notes to pick, let’s have a look at some of the common techniques that jazz arrangers use. These methods can stand on their own with many of them being used as background ideas behind melodies or improvised solos. You can also layer multiple of them on top of one another, or completely isolate them. There are many options to choose from and they provide a great template where you don't need to fully create a countermelody line from scratch.

Riffs play a major role in jazz and have been a part of jazz vocabulary since the inception of the art form. They operate as simple melodic devices that repeat and can form the melody or accompaniment of any song. You can find them in the melody of blues songs which riff over a four bar phrase that is repeated once or twice within a form, as well as in swing era sax hemiolas and piano montunos in latin music. As a countermelody technique they can provide rhythmic and harmonic interest while not overshadowing the melody line and are fantastic for background figures in a solo.

To create a riff you want to draw upon a limited number of notes and try to make a short melodic phrase with them. Pentatonic scales are perfect for this and offer a great starting point. Once you find a motif you like, simply repeat it. As the chords change you can shift certain notes to reflect the harmony, move the whole riff higher or lower to have the same relationship with the progression, or maintain the same riff regardless of how the harmony may impact it.

One O’Clock Jump

Count Basie

Pads

Moving over to a completely different technique we have pads, which really are a fancy name for long notes in a jazz setting. Typically, they exist as harmonic cushions which provide richness to a setting without stepping on the toes of any particular melody or instrument. The trick to a good pad is to add some layer of interest that goes beyond writing consistent semibreves/whole notes which follow an interesting guide tone line. This doesn’t have to be the case, but it will provide more joy to the musician playing the line.

To create a pad, find a guide tone line you like, whether that be in relation to the melody or the chord progression, and assign it to an instrument. In big band writing pads are commonly harmonised within a section to add more weight to the ensemble but unison can also be effective.

Pennies From Heaven

Arr. Lennie Niehaus

Hits

Hits are the direct opposite of pads. Instead of using long notes, a hit is a short note that is used to add exclamation to a phrase. They can reinforce important parts of the melody, act as a concluding statement, or add syncopation and excitement to a line. If you’re a fan of pop or latin horn writing you’ll have definitely heard this technique used many times

To write a hit, find a location you want to add musical exclamation and find a note that works with the chord progression. You then choose a short rhythm, typically an off beat quaver/eighth note that aligns with the melody or lands in a rest. Use your judgement as to whether the hit works in that location and if not, try other beats in the same bar before trialling other locations. It is also common for multiple hits to be used side by side instead of just using a singular note.

In A Mellow Tone

Arr. Frank Foster

Call & Response

Another great option is call and response which has been a major component of African American music well before the creation of jazz and can be heard in numerous examples over many different styles. The technique includes two components: a melody line which establishes a motive (the call), and a countermelody line which repeats the motive directly afterward (the response). Sometimes the call can be a singular instrument or voice while the response is a choir or collective group of instruments, however there is no hard and fast rule with the orchestration of the technique. The primary component to a successful call and response is enough space after the initial melody has been stated. If there is no room for a response, the countermelody will simply double up over the melody which can be chaotic and diminish both voices.

The Best Is Yet To Come

Arr. Quincy Jones

Counterpoint

Unlike the previous four options, counterpoint is considerably more dense to unpack. At the surface level the term applies to any time more than one line is played together. This could be when two or more instruments are playing homophonically or polyphonically. However, the term counterpoint is also associated with a number of rules that were established centuries ago for Western classical music. For the sake of this resource, those rules aren’t necessary and I am only using the term to describe writing countermelodies that fall out of the classification of the last four techniques.

The foundations of using counterpoint work in a similar way to what we discussed earlier with guide tone lines and relating a counterline to the melody through target notes. We can expand on this by looking at the different types of motion which exist when two lines interact with one another. Generally there are three options available:

Similar (when both lines follow the same contour as the melody)

Contrary (when the lines move away from each other)

Oblique (when one line stays on the same note while the other moves in any direction)

Each type of motion offers a different experience, with contrary and oblique motion used to distinguish individual lines from one another and similar motion helping multiple voices feel like a collective. If the idea is to write a countermelody and not just a harmonized part, a mixture of all three will help the line be more interesting.

Are You Real

Benny Golson

We also need to be aware of the proximity of lines with one another. In the classical counterpoint world, crossing paths is strictly against the rules, however it is definitely an option in jazz. The main point to be aware of is that when you cross paths or get into close proximity with a melody line, you obscure both lines. There are ways of lowering the obscurity such as with different densities of rhythm where one line may be more of a pad and the other is a moving melody, or through utilizing different registers of instruments where even though the lines cross each line sounds unique due to the timbre of the register they are in. If that all feels too much, a simple solution is to avoid crossing paths and to voice the counterline either higher or lower than the melody.

Finally, the last area to be aware of when writing a counterline directly over a melody is the rhythmic density of both lines. If both lines are highly rhythmic it will create a level of chaos in the music where it takes away the clarity of both lines. The most common approach is to have the lines rhythmically compliment each other where each one takes turns being more complex.

Whichever option you choose when it comes to writing a countermelody, the trick is to treat it as seriously as composing a melody. That way the musicians will enjoy performing any line you write and your music will be rich with fantastic lines. At first I would suggest starting with using one countermelody technique at a time and as you feel more comfortable, try experimenting with multiple at the same time.

In a big band setting we have access to a lot of instruments so it is quite common to have three or four different lines running simultaneously. A great example of this is during a solo section where you may have one person improvising while each section is playing a different background part.

The Takeaway

There are so many ways to write a melody, so much so that it’s probably impossible to incorporate all of them into a single example. This resource is meant to help you find options when you’re in a hole and are looking for techniques to experiment with to find a way out. You have the freedom to focus on just one element of a melody or try to incorporate them all, there are no bad options.

After travelling quite a long journey to feel comfortable writing my own melodies, the only thing I would suggest is that editing is far easier than creating. Try to get something on the paper no matter how critical you may be because then you have something to work with. It doesn’t matter if it sounds bad to you, it is simply a starting point which will make the next step easier. And anyway, if it really is terrible you can always start from scratch another time.

With composing melodies and countermelodies now in the bag, it’s time to move on to big band specific methods. Namely shout sections and solis. Both of which are a staple in the jazz tradition. But like always, you’ll have to read about that in the next resource.